Interview with Rebecca Shaykin: The Exhibition "Draw Them In Paint Them Out" in New York

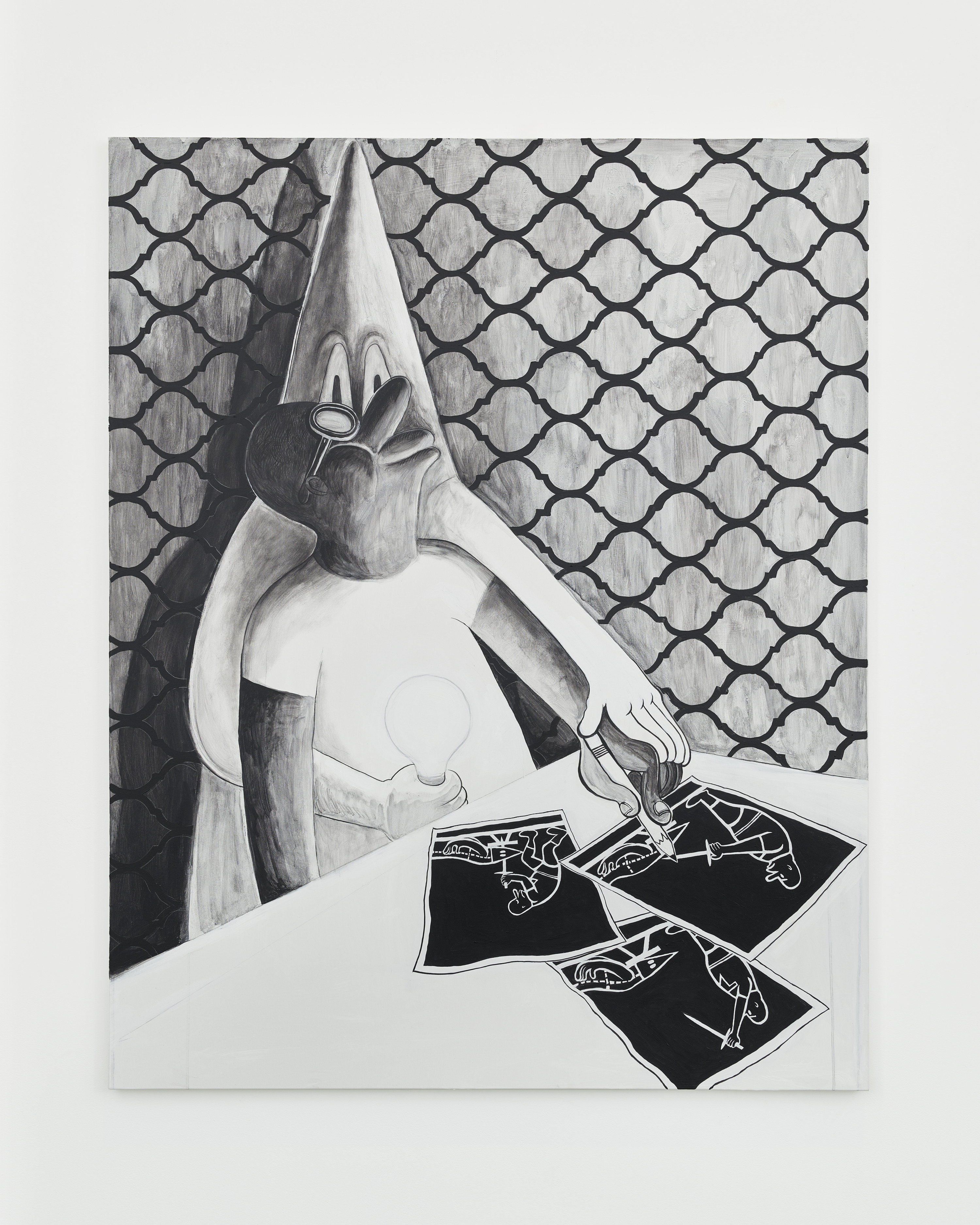

The curator of the Jewish Museum discusses the dialogue between artists Trenton Doyle Hancock and Philip Guston on racism, antisemitism, and historical memory.

It is intellectually gratifying to visit thoughtful and challenging exhibitions on view in New York, and this dual presentation is one of them – it makes you think, question, and look again at the works. An aspiration of art created to serve social justice, as conceived by Trenton Doyle Hancock and Philip Guston, is fulfilled. The exhibition is curated by Rebecca Shaykin of The Jewish Museum. For Spaghetti Boost, I asked Rebecca several questions about this relevant and politically significant exhibition.

NCM: How did the idea for this show come about?

RS: The idea for this exhibition came quite some time ago. For a long time, we’ve been noticing here in the U.S. an unprecedented rise in both antisemitic attacks and anti-Black violence, going back to 2017, to The Unite the Right rally in Charlottsville, Virginia. We were beginning to see how antisemitism and racism have its roots in this white supremacist ideology. We felt that as a Jewish museum, we needed to do something to address this crisis. We were thinking a lot about Philip Guston, who, of course, was the great 20th-century Jewish painter who made a lot of satirical works about the Klan in the late 1960s and early 70s. We wanted to find a way to make these works more relevant and current for our moment today. When I came across Trenton Doyle Hancock and particularly his paintings from the Step and Screw series, it became very clear to me that this was a perfect pairing to talk about this moment, to talk about where we’ve been and where we are going. It was also important to have both the perspective of a Jewish artist and a Black artist in dialogue together to talk about these issues and how we can move forward.

NCM: What was the response of your audience to this exhibition?

RS: The response has been overwhelmingly positive. Every time you do a show that has a real political charge to it and deals with sensitive issues, you want to make sure you are getting it right. We are confident with our final product, and I think the response we have gotten from our audience is the reflection of our deep thinking and the thorough approach that we have taken. We had a private opening on the night after the election, and it was a very difficult moment, but it became the exact right thing to do. This exhibition is meeting our moment in a way that we could have never expected and certainly did not hope for. We saw immediately how this exhibition would provide an outlet for the people for their anger and outrage, as well as a chance to be in community with each other and give people an opportunity to commune with both of these artists on an individual basis.

NCM: Was the choice of works that reflected Guston’s problems with his Jewish heritage intentional and if so, why?

RS: I wouldn’t say Guston had a problem with his Jewish heritage, but did he wrestle with his identity as an assimilated Jew? I think so. It was important for us to anchor our understanding of Guston’s Klan work in the artist’s biography and his lived experience as a Jewish-American artist who had assimilated and changed his name at an early age. As an identity-based institution, we often lean on biographical interpretation to guide us through our curatorial practice. Many Jewish artists assimilated in the 1930s as a reflection of rising antisemitism in the U.S. and the rise of Nazi ideology in Europe. People were responding and adapting in the ways they needed to.

NCM: What are the advantages and disadvantages of curating a politically sensitive show such as this one?

RS: When you curate a show that is in some respects a response to current events, while working with an institution that requires time to plan, develop, and execute an exhibition, there can be certain challenges. We cannot always predict what exactly the news cycle will be by the time the show opens. The idea for this show came to me seven years ago, I started working on it in earnest four years ago, so we didn’t know if, by 2024, the idea would still be as relevant. Because of the cyclical nature of the moment we are living in right now, as we see the ascendance of white supremacist ideology again, it is, regrettably, even more relevant. The advantage here is that people are responding to it on a very personal level. This is something we are all affected by in one way or another. Taking people of all backgrounds through the show and seeing them identify with these works on view is very gratifying.

NCM: What is the role of an institution in this changing world of ascending right-wing ideology? How can they stay relevant?

RS: The main role of museums is to be providers of public education. We need to be places that foster dialogue and stimulate debates, both about historical times and our present moment. We are a Jewish museum, but we are also an art museum, and our role is to provide a platform for artists to engage with history and the current moment and to get their voices out there. We need to continue to let the artists guide us through this time.

Cover image: Installation view "Draw Them In, Paint Them Out": Trenton Doyle Hancock confronts Philip Guston at the Jewish Museum, NY, 8 November 2024-30 March 2025. Photograph by Gregory Carter / Document Art

Nina Chkareuli-Mdivani is a Georgian-born, New York-based independent curator, writer and researcher. She is the author of King is Female (2018), the first publication to investigate issues of gender identity in the context of the historical, social and cultural transformation of Eastern Europe over the past two decades. Throughout her career she has lectured worldwide and published numerous articles for magazines such as E-flux, Hyperallergic, Flash Art International, Artforum, MoMa.post, The Arts Newspaper and many others.

Her research delves into the intersection of art history, museology and decolonisation studies, with a focus on totalitarian art and trauma theory, themes he has also explored in the more than ten exhibitions he has curated in New York, Germany, Latvia and Georgia.