Androids and Electric Sheep: How Technology Is Dehumanizing Us

From humanoid robots like Protoclone and MagicBot to artificial empathy: a journey into the unsettling future of artificial intelligence.

Protoclone is a “graceful” musculoskeletal android designed to faithfully replicate the anatomy and movement of the human body. I'm quite sure you’ve already seen it in a viral video: there’s a dark room, with cables hanging from the ceiling—and there it is, the robot, suspended from a trapeze like a cyberpunk circus acrobat. For a few seconds, it hangs still. Then suddenly, it begins to twitch and writhe: synthetic muscles contract beneath a translucent skin, specifically designed to enhance the hyperrealistic effect of its artificial anatomy. The reels I’ve seen usually follow up with an infographic presentation of the prototype’s structural details, along with more practical demonstrations of its mobility—admittedly, quite astonishing.

I often come across similar content on social media. Recently, I watched a robot run outdoors for four minutes straight. From what I gathered, the company behind MagicBot (that’s the name of the android runner) is working to have it compete in a half marathon in Beijing, alongside 12,000 flesh-and-blood runners. Intriguing? Incredible? Frightening? There’s something I can’t help but notice whenever I check the comment sections of these videos: a widespread sense of horror, repulsion—even dismay—accompanies the spectacle of cutting-edge robotic feats.

Berlinde De Bruyckere, Hauser & Wirth, New York City, NY

Berlinde De Bruyckere, Hauser & Wirth, New York City, NY

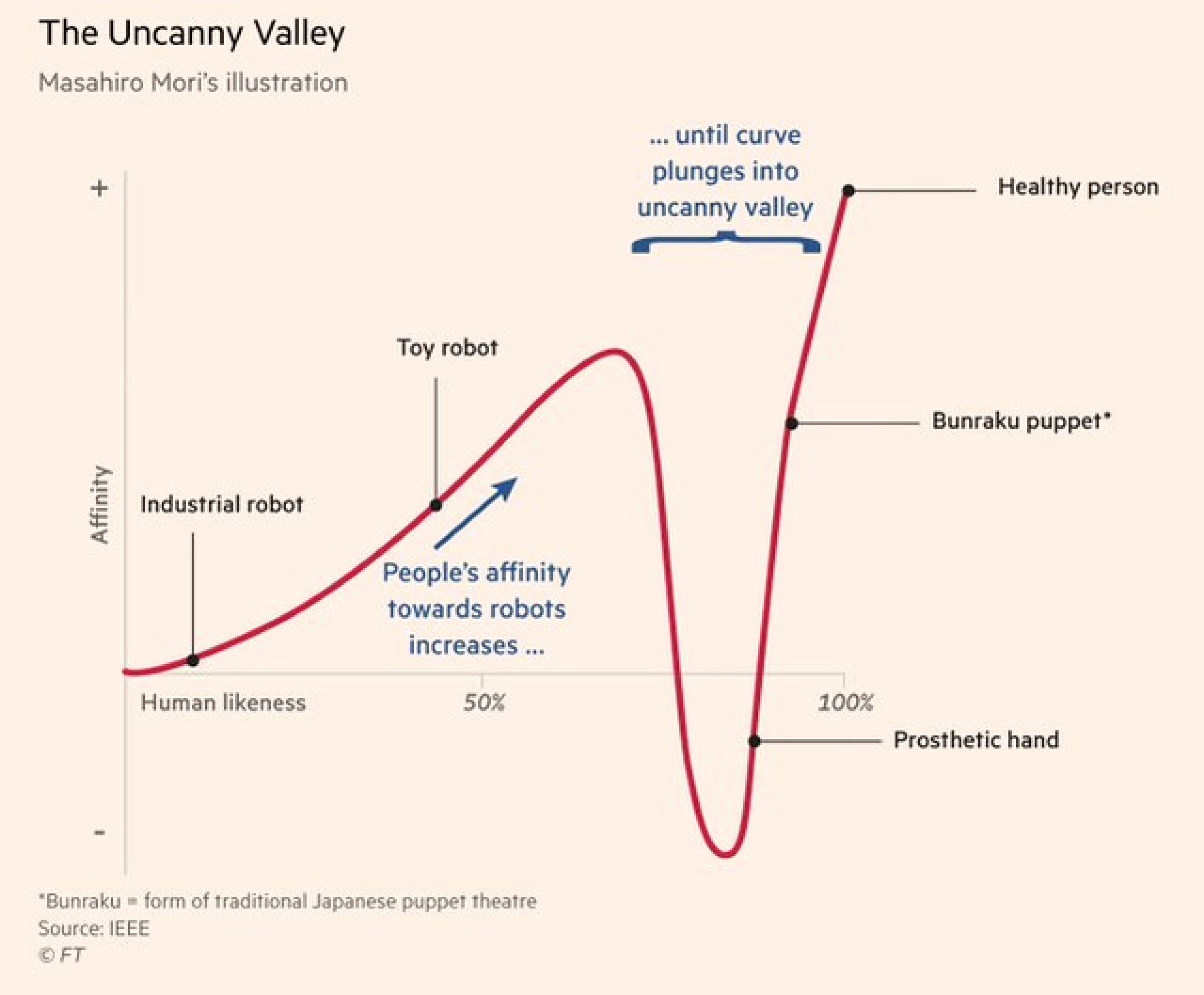

Whether it’s SoftBank’s “Pepper,” a prototype with silicone skin, or androids that mimic even the micro-movements of pupils, the collective reaction is often unanimous: unease. It seems we’re all, ultimately, victims of what Japanese engineer Masahiro Mori dubbed the “Uncanny Valley” back in 1970: when a robot becomes too similar to a human being, instead of reassuring us, it unsettles us. Strange? Logically speaking, the more a machine resembles us, the more it should evoke positive feelings—empathy, even affection. But the Uncanny Valley defies pure rationality: androids that are too “human” fall into a perceptual grey zone between familiarity and primal revulsion. So, when we face something that appears alive but isn’t (or is alive in a way alien to us), it sparks a deep-rooted fear. It's an instinct, embedded in our human core. And I believe that it’s this very “essence” that we now feel—somehow—threatened.

Let’s put it this way: for centuries, we were cradled by the idea that Man was the center of the universe. Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man perhaps best encapsulates the notion of humanity as “the measure of all things.” The evolution of modern technology, epistemological thought, and progress: since the Renaissance, nature often became a mere instrument, knowledge exalted our control over the world, and technology turned into the extension of our will. But when that “measure” slips into the illusion of absolute supremacy, unexpected cracks begin to appear: that ideal of harmony—already shaken by cosmological discoveries and rationalist movements—now faces the far more dizzying horizon of new digital and genetic technologies. The notion of “the measure of all things” collapses in the face of hybrid realities, where organic and artificial blur. It’s no longer just about displacing humans from the center of the universe—it’s about redefining the very boundaries of what it means to be human. When science becomes a creator, the proportions invert: we no longer govern technology—it redefines us.

The Uncanny Valley Graphic, Masahiro Mori, 1970

The Uncanny Valley Graphic, Masahiro Mori, 1970

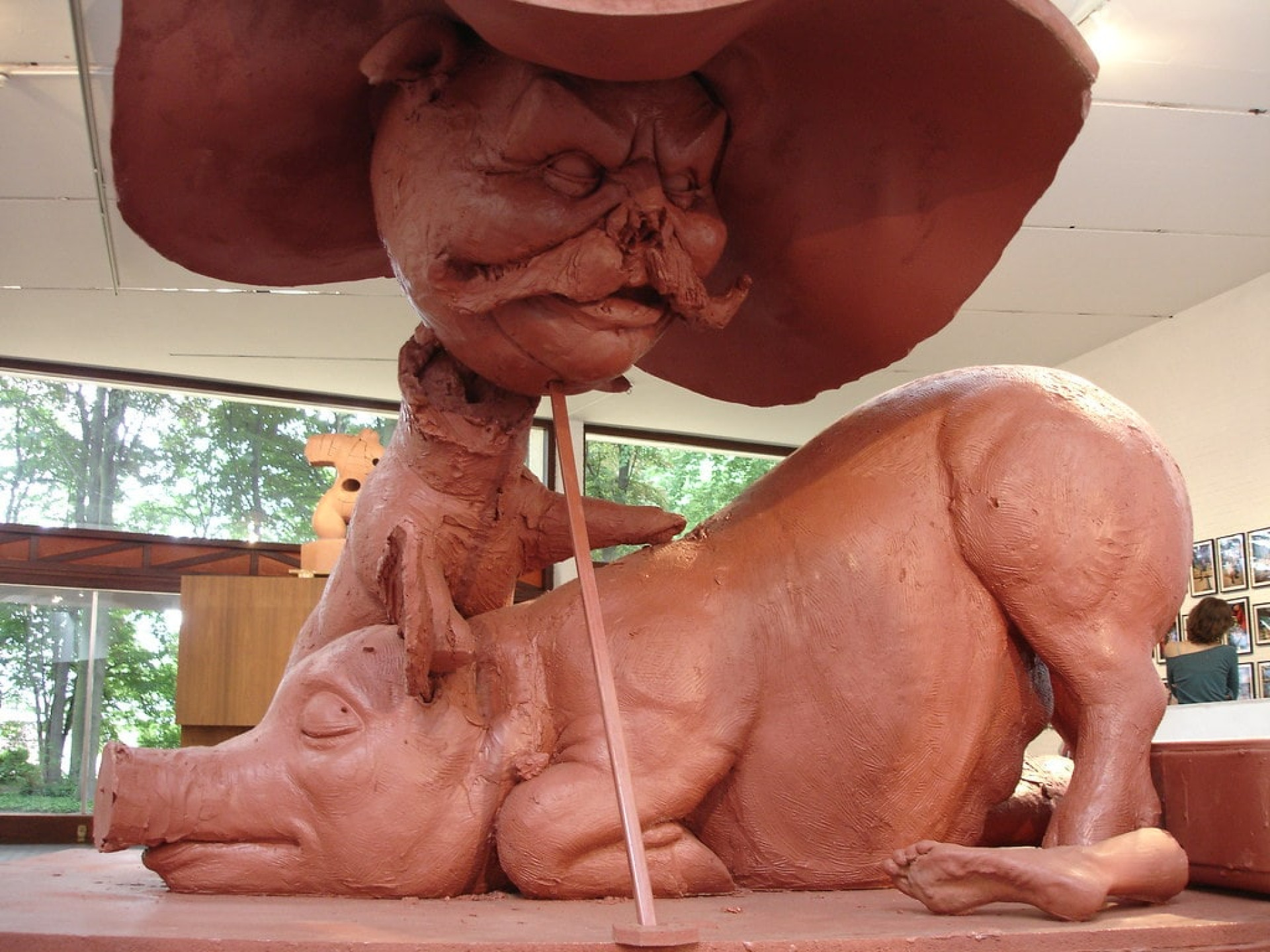

The humanistic revolution suddenly seems to have derailed from the anthropocentric tracks that sustained it for half a millennium: science is gradually replacing the scientist. It must be said, this vaguely apocalyptic mood didn’t begin with ChatGPT learning to write poems, novels, and dissertations. Think about art, which often captures the echo of a distant future decades in advance: back in 1992, the exhibition “Post Human” spotlighted an aesthetic of mutant bodies, hybrids, fusions between man and machine, silicone and flesh, artifice and biology. At the height of technological fervor, curator Jeffrey Deitch showcased a humanity abandoning the centrality of the classical self to embrace a new form of existence.

Why the '90s? Perhaps because the euphoria of the new economy, Silicon Valley’s boom, and the rise of biotech conveyed the feeling that anything was possible. Dolly the sheep, the internet, GMOs: newspapers were filled with articles sketching a future where we’d hack genes to create custom organisms, and scientists would soon find ways to interface with machines to enhance our physical and mental capabilities. Pop culture—and art, of course—absorbed this ferment to build a visual imagination that was aggressive, hypnotic, even tasteless at times, echoing the cinematic flair of Blade Runner, Videodrome, Ghost in the Shell, Terminator, Akira.

There was so much—too much—excitement in those proclamations. Like any optimistic high, they hinted at transcending human limitations—disease, aging, imperfection—and entering triumphantly into the age of the cyborg, the transhuman. The Post Human exhibition heralded the start of an anthropological revolution, one that promised to heal our age-old anxieties—only to, perhaps unexpectedly, create many more. Yet Deitch’s intent was to capture a moment of transition, an epochal shift: the desire to break through the boundaries of flesh, to conceive of identity as something fluid, something potentially alterable. It was a hymn to self-determination, a bold exploration of the body as a field of ethical and aesthetic experimentation.

Matthew Barney, The Cremaster, 1994

Matthew Barney, The Cremaster, 1994

Thirty years ago, it must be said, the post-human imagination was mostly theoretical. And when it entered the art world, it took analog, physical, metamorphic forms. The cyborg—whether nightmare or dream—was an aesthetic and intellectual concept, envisioning a future of symbiotic coexistence between man and machine. Today, at least in digital terms, that prophecy seems to have fully materialized. Generative AI writes articles and marketing campaigns, composes music, creates memes, graphics, and images. In no time, it has become part of schools, businesses, households, and everyday software. And yet, fears and concerns abound. The fear—whether inflated or justified—is that humans will be gradually replaced, that the brilliance of human invention may erase humanity itself. Robots, androids, hyperrealistic prototypes merely shift this “coexistence” onto a tangible, material plane. And that’s where panic sets in: AI, while confined to a screen, still feels relatively harmless. But once it enters our physical space, everything changes.

The Post Human aesthetic warned us precisely of this: we were crossing a threshold, and we couldn’t pretend otherwise. Now, having long passed that threshold—into a world of physical and digital hybrids happening daily (think smart prosthetics, augmented reality, subcutaneous medical chips, or social media as extensions of our identity)—we realize just how prophetic those works were. In 1992, to be fair, some critics accused the exhibition of being too “commercial,” of chasing the cyber trend, of trying to shock with extreme imagery. And it's true: shock was an integral part of those artists' language, who had no intention of comforting the public. But three decades on, a second, clearer interpretation emerges: that of a collective body in transformation, aware that the line between natural and artificial, biological and mechanical, would grow increasingly thin. And from that point onward, we would find ourselves increasingly undefined, in constant transition toward something else.

Paul McCarthy, Studies for Piggies, Exhibition ‘AIR BORN AIR PRESSURE’, Antwerp Middelheim Museum, 2007

Paul McCarthy, Studies for Piggies, Exhibition ‘AIR BORN AIR PRESSURE’, Antwerp Middelheim Museum, 2007

The anxiety we feel watching next-gen androids that talk, dance, or clean the house is, ultimately, a natural response to change—which is always ambivalent: we desire it, yet we’re terrified by it because it opens up unfamiliar scenarios we’re not—yet—equipped to navigate. Freud defined the uncanny (Unheimliche) as something familiar and yet alien at the same time. He added that this condition generates profound disorientation, as it disturbs the very parameters we use to recognize reality. The same happens with humanoid robots: they reflect an image that is intrinsically familiar (a body with a face, limbs, expressions) and simultaneously disturbing, because there is no real life “there.”

In the end, it’s the principle of the double. If it scares us, it's because it reminds us that we are not monolithic, perfectly coherent beings, but full of contradictions and shadowy zones. Robots—or LLM systems—display a mask of humanity without any true lived experience, which forces us to confront the fragility of our very concept of being alive. In other words, the Uncanny Valley is nothing more than the reflection of a fissure already present within us. And here the lesson of Post Human returns. We’re not simply witnessing a linear progression of technology; we’re undergoing an anthropological mutation that enacts a profound contradiction: we want to be “more than human,” but at the same time, we’re terrified by anything that gets too close to being human without truly being it.

In the ‘90s, with the pioneering spirit of the time, many artists celebrated identity fluidity, the possibility of building a custom-made body, of transcending the boundaries of flesh. Today, now that this fluidity manifests more tangibly, we also discover its contradictions—and the harsh backlash, as seen in the rise of hyper-conservative right-wing movements across Europe and beyond. Perhaps, in light of today’s reactionary tides, we should reconsider the sociological meaning of that artistic era. With the right lens, we might begin to see it as an explicit call to open our eyes to the fact that identity is not set in stone—it is a perpetual becoming, and sometimes that becoming is disturbing. The art of that time tried—awkwardly at times—to stage the complexity and ambiguity of this shift.

Berlinde De Bruyckere, Hauser & Wirth, New York City, NY

Berlinde De Bruyckere, Hauser & Wirth, New York City, NY

If we’re trying to understand why that aesthetic still speaks to us so intensely today, perhaps it’s because in it we see the origin of our current contradictions: the body (or mind) as a testing ground, the desire to overcome biological aging, and the fear of losing one’s soul; the fascination with the future and the fear of being replaced by a more efficient technology—on every level. In short, Post Human showed us that we were already “beyond human” in our imagination, and yet still deeply attached to our old anxieties.

Today, in a radically different landscape—with social media spreading information and fears in real time, and artificial intelligence rendering obsolete hundreds of once deeply “human” professions—those same anxieties resonate even more powerfully. We’re no longer in the realm of hypotheses: we have robots that can interact with audiences, AI that composes music and “reasons” (albeit without consciousness) in ways eerily similar to our own. The feeling of disorientation and unease should not be dismissed or demonized. It’s normal to feel fear in the face of such a radical leap in our concept of humanity. Perhaps we must learn to live with that unease, to understand its deeper roots, and not dismiss it as a mere fear of the “other.” Because, in truth, the humanoid robot—or a generative AI model—isn’t just any “other”: it is our imperfect and enhanced copy, our technological double.

The point is, we can no longer postpone a serious debate about what it means to be human in an age of technologies that not only accompany us, but potentially equal—and sometimes surpass—us. We can admit to feeling unsettled, uncomfortable, even afraid. But as the art of the 1990s tried to show us, this unease can become a creative force: we can use it to redefine our concept of identity in a more dimensional way, to exercise our capacity for empathy, and—paradoxically—to rediscover a more complex and conscious sense of humanity.

In 1992, after decades of artistic experimentation in conceptual, abstract, metaphysical territories, Post Human brought the “body” forcefully back to the center of aesthetic inquiry. A different body—hybrid, at times deformed—but still a body. If there’s a lesson to learn today from that exhibition, it’s that the definition of “human” is not an absolute concept. The Uncanny Valley is a natural place of disorientation—but it can become a place of discovery. And, above all, rediscovery. Maybe, in the end, we’ll learn to love this eerie valley, because it reminds us that we have always been searching for an answer to what it truly means to “be.” And maybe that’s not such a bad thing, after all.

Cover image: Charles Ray, Fall ‘91, 1992, Glenstone Museum, Potomac, Maryland, USA.

Creative, teacher and expert in visual culture, Alessandro Carnevale has worked on TV for several years and has exhibited his works all over the world. In 2020, the Business School of Il Sole 24 Ore included him among the five best Italian content creators in the artistic field: on social media he deals with cultural dissemination, covering a wide spectrum of disciplines, including the psychology of perception, semiotics visual, aesthetic philosophy and contemporary art. He has collaborated with various newspapers, published essays and written a series of graphic novels together with the theoretical physicist Davide De Biasio; he is the artistic director of an open-air museum. Today, as a consultant, he works in the world of communication, training and education.