Antonella Soldaini and her collection in her home-studio in Rome

The interview and journey through curator Soldaini’s collection.

Antonella Soldaini is a long-standing researcher with a remarkable international background. In 1981, she was already in New York to continue her studies at C.U.N.Y. University, and in 1988, still in the U.S., she began her curatorial career at the Wexner Center for the Visual Arts in Columbus.

She has an impressive curriculum of publications and exhibitions, in which meticulous editorial and curatorial work has gone hand in hand with in-depth research on individual artists, conducted over years of intensive sessions in archives and studios. Her home-studio in Rome—where she lives when not in Milan, the city that has professionally adopted her for more than thirty years—is filled with bookshelves in every room, even the bedroom, and with artworks by the artists she has long engaged with and worked alongside. It is, in a way, a synthesis of a life lived in close contact with remarkable artists. Beginning with the British artist David Tremlett, who created a site-specific work on the round ceiling of the studio's entrance: “They are mixed letters that, when assembled, form the names of the cities she has traveled to.”

Antonella, is this your real home?

“Yes, in Milan there’s just a mountain of books. And a bed.”

David Tremlett (top, detail) Germany to Australia, 2011

David Tremlett (top, detail) Germany to Australia, 2011

So the artworks are here in Rome?

"We curators are not born collectors; what you see is a collection of works by some of the artists, or the families managing their archives when they can no more, whom I’ve worked with. When they feel the collaboration went well, they’re often happy to gift you something. Obviously, this is a practice that’s only acceptable in the private sector, where I work."

Tell us about a work you're particularly attached to.

“I’d like to talk about one I lost. A drawing dedicated to me by Sol LeWitt—I lost it during a move in the chaos, and I’ve never found it again, it was a huge heartbreak! It was a beautiful work; he gave it to me after an exhibition. I met Sol because the Wexner Museum, where I worked in the ’90s, asked me to go and interview him. He hosted me at his home for a few days, and during that time, I met his wife and daughters. He was very kind, but he didn’t want to give me an interview. Still, we stayed in touch from then on. I later involved him in a project at the Museo Pecci, where he did a work for free, I think partly because of the friendship that had started during those days together.”

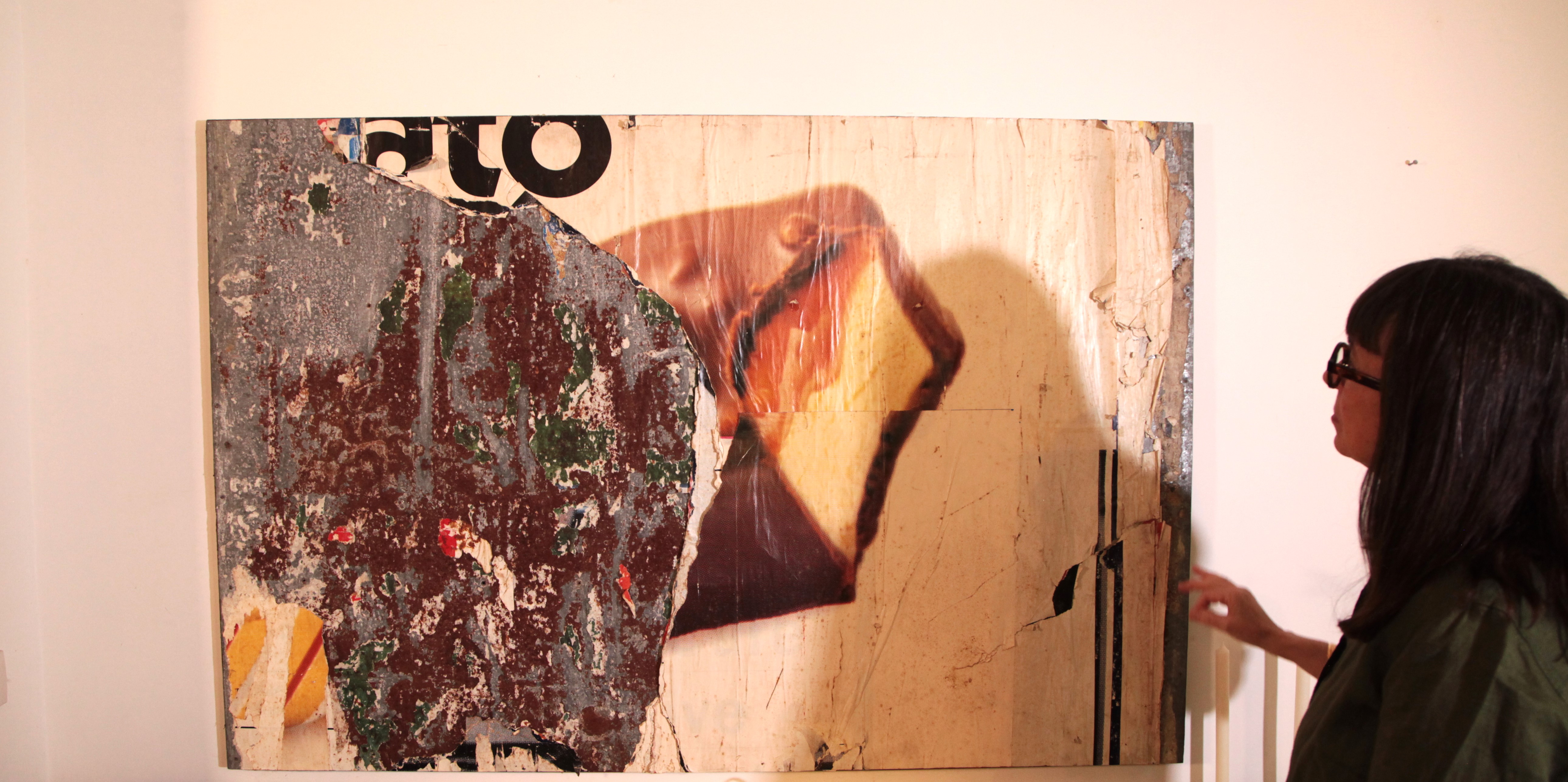

I see three major works by Rotella—an artist you worked with extensively when you were director of the Mimmo Rotella Institute.

“They’re three décollages that came from the artist’s family. One of them is almost informal in style, very large, and one I’m especially fond of.”

But I also see some small, precious pieces.

"For example, a small bowl, some ceramics by Fausto Melotti, and one of his small multiple sculptures."

You worked for many years on various exhibitions and editorial projects with Germano Celant, whom you met in the U.S. when your curatorial work was already well established in museums. He was also a passionate collector, especially of artworks. His home-studio in Milan was like an international museum—I remember seeing it in a design magazine years ago, with works by Kiefer, LeWitt, and many others.

“In the beginning, he was probably more detached—the works came to him almost by chance from artist friends. Later, it became a serious commitment. He really loved books and the artworks he liked to surround himself with. And artists really wanted to be part of his collection.”

So your own collection is, above all, an emotional landscape within your domestic and working space.

“These artworks give me warmth; I feel comfortable when surrounded by them. Each piece reminds me of a positive relationship—and luckily, they’ve all been very beautiful relationships.”

I see, for instance, a major wall piece by Remo Salvadori, someone you’re deeply connected to. I know his monograph (published by Skira), curated by you and edit by Studio Celant (where you’re curatorial consultant and research lead), just came out, and in July, you’ll be co-curating his retrospective at Palazzo Reale in Milan with Elena Tettamanti.

“I’ve known Remo for a long time, just as I have Marco Bagnoli, for whom I worked on a monograph edited by Celant years ago, and for which I wrote the chronology.”

There’s also a work by Marco Tirelli, with whom you’ve collaborated on several projects.

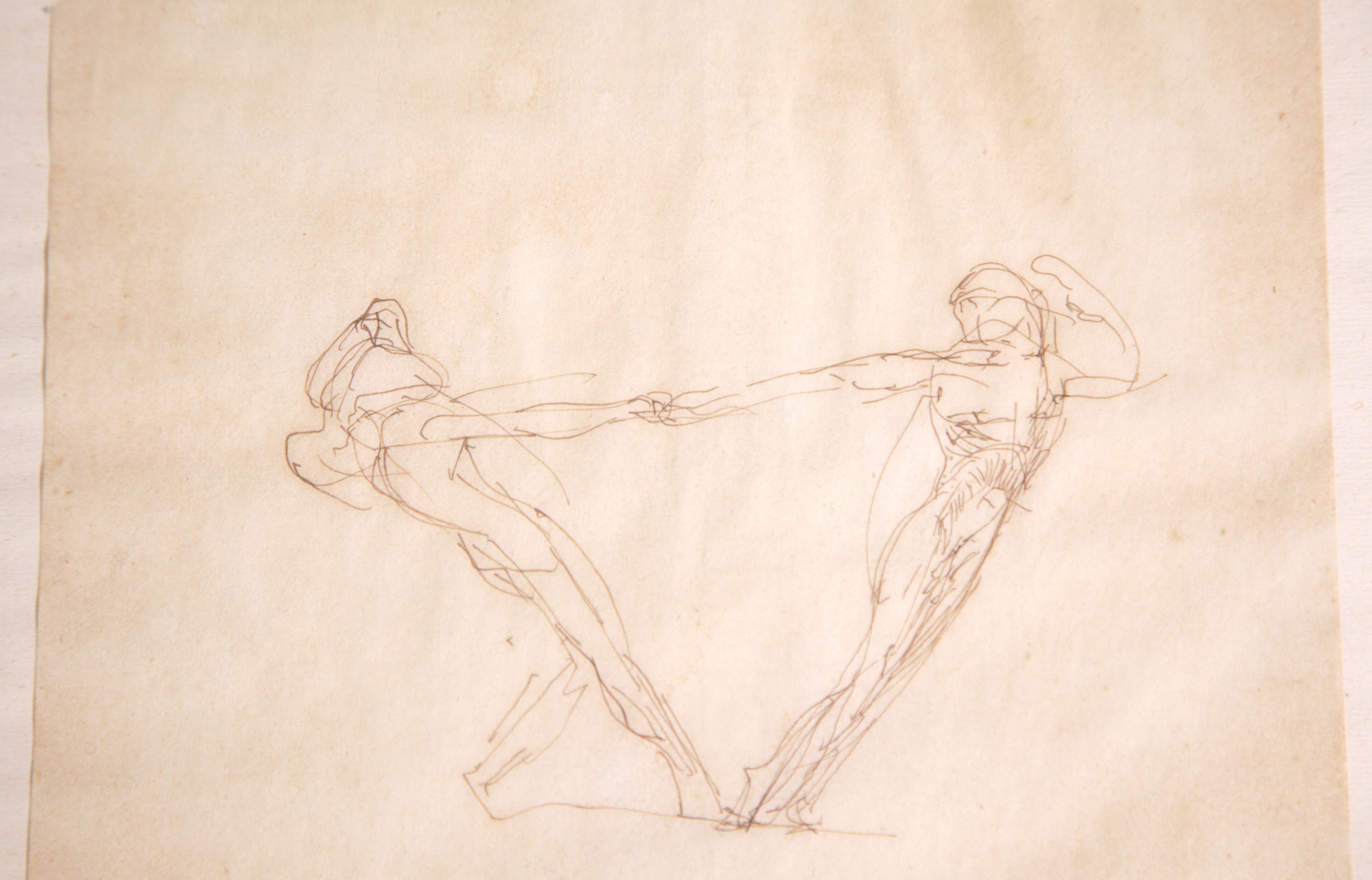

“One of his mysterious, geometric pieces. Then there’s Umberto Cavenago, another friend. Also a drawing by John Wesley—when his show was held at the Fondazione Prada in Venice, I worked on the chronology for his major monograph, which he really liked. Not contemporary, but I also have a small drawing by Giulio Aristide Sartorio, given to me by his son for a paper I wrote on the artist’s work, back in my university days—I'm quite attached to it.”

Other works?

“Certainly Marco Bagnoli again, and then Alberto Garutti, with a crystal piece that only lights up at night—linked to the time we did a project in Fabbrica, in the municipality of Peccioli, Tuscany, which marked a major turning point for him. Then Giulio Paolini, with whom I’ve shared several projects, Michele Zaza with an installation involving photography and wood inserts, and also Giorgio Vigna and Tadashi Kawamata, who built me a small table. And a small photo of me, heavyset, by Erwin Wurm, whose exhibition I curated at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney.”

So artists, then, are generous?

“Younger ones, not so much. With some lovely exceptions. I have a little piece I adore by an artist I never even worked with, but who wanted to gift it to me—his name is Simone Settimo.”

Cover image: Antonella Soldaini in her home-studio in Rome.

Lorenzo Madaro is curator and professor of History of Contemporary Art at the Brera Academy of Fine Arts in Milan, where he also teaches Museology of the Contemporary.

He is a regular contributor to the daily newspaper ‘La Repubblica’ and the weekly ‘Robinson’ of the same publication. For the Milan pages of the newspaper, he has edited columns dedicated to artists' studios in the city, galleries and the archives of artists and designers. He collaborates with the Poli Biblio-museali di Puglia and Flash Art and is a member of the scientific and curatorial committee of the Fondazione Biscozzi Rimbaud in Lecce. Recent exhibitions he has curated include: Dimensionare lo spazio (A Arte Invernizzi, Milan, 2024), Yuval Avital. Bosco di Lecce (MUST, Lecce, 2023) Umberto Bignardi. Di nuovo a Roma (Galleria Valentina Bonomo, Rome, 2023); Pino Pinelli (Dep Art Out, Ceglie Messapica, 2023), Mimmo Paladino. He will have no title (Palazzo Parasi, Cannobio, 2023); Bringing everything back home (Museo delle Navi Romane, Nemi, 2023); Federico Gori. L'età dell'oro (Museo nazionale di Taranto, Taranto, 2022 - winning project of the PAC competition of the Ministry of Culture); Sebastiao Salgado (Castello di Otranto, Otranto, 2022), Andy Warhol (Monopoli, Castello Carlo V, 2022), Stati della materia (Gagliardi and Domke, Turin, 2021); Gianni Berengo Gardin. True Photography (Castello, Otranto 2020); Umberto Bignardi Sperimentazioni visual a Roma (1963-1967) (Galleria Bianconi, Milan, 2020); Silenzioso, mi ritiro a dipingere un quadro (Galleria Fabbri, Milan, 2019). He has collaborated with MAXXI (Rome), Quadriennale di Roma, Treccani Literature Festival and other institutions.