Brain Rot: a cultural diagnosis

"Brain Rot" isn’t just a word. First, because there are two words—so it would be more accurate to call it a phrase—but more importantly, because “brain rot” has become the merciless yet strikingly effective cultural label of 2024.

Named Word of the Year by Oxford University Press, publisher of the Oxford English Dictionary, "brain rot" conjures a disturbingly organic image that captures—quoting directly—the "alleged deterioration of a person’s mental or intellectual state, largely as a result of excessive consumption of material (currently, in particular, online content) considered trivial or unchallenging."

At its core, Brain Rot is the name of a (self-)diagnosed illness that no one believes they personally suffer from. We are all highly skilled at recognizing its symptoms—provided they appear in others: reduced attention spans, compulsive consumption of Shorts, Stories, and Reels, and the loss of awareness of time spent on social media. We know the problem exists (because it most certainly does), but we don’t think it applies to us. Not that dramatically, at least. Or does it?

Let’s take a step back: where did the term Brain Rot originate? The word itself has been around for centuries, but on the internet, the phrase has taken on a relatively new meaning. Specifically, starting in the early months of 2024, the hashtag #brainrot was shared thousands of times on TikTok becoming viral. In the videos that sparked the trend, young people—often very young—would share accounts of strange (and sometimes tragically comical) behaviors they had experienced after spending hours scrolling content on the platform. Some confessed to mistaking a TV remote for their smartphone, while others described reflexively trying to interact with inanimate objects as though they were touchscreen displays. The hashtag soon transcended TikTok’s borders, “infecting” (interesting how internet terminology mirrors medical jargon) other platforms until it caught the attention of Oxford Press, which shortlisted it as one of the terms that best represent the year now drawing to a close as I write.

The growing awareness of the risks and “toxic” dynamics associated with the obsessive consumption of short (or ultra-short) videos—a hallmark of social media’s current content landscape—has turned Brain Rot into a true snapshot of 2024. Born jokingly on the internet, the phrase has absorbed a broader cultural—and, to some extent, even scientific—weight that made it more than worthy of being named Word of the Year. Now, let’s take a moment to unpack what’s really at play here from a psychological and neuroscientific perspective behind this hyperbolic image of a decaying brain.

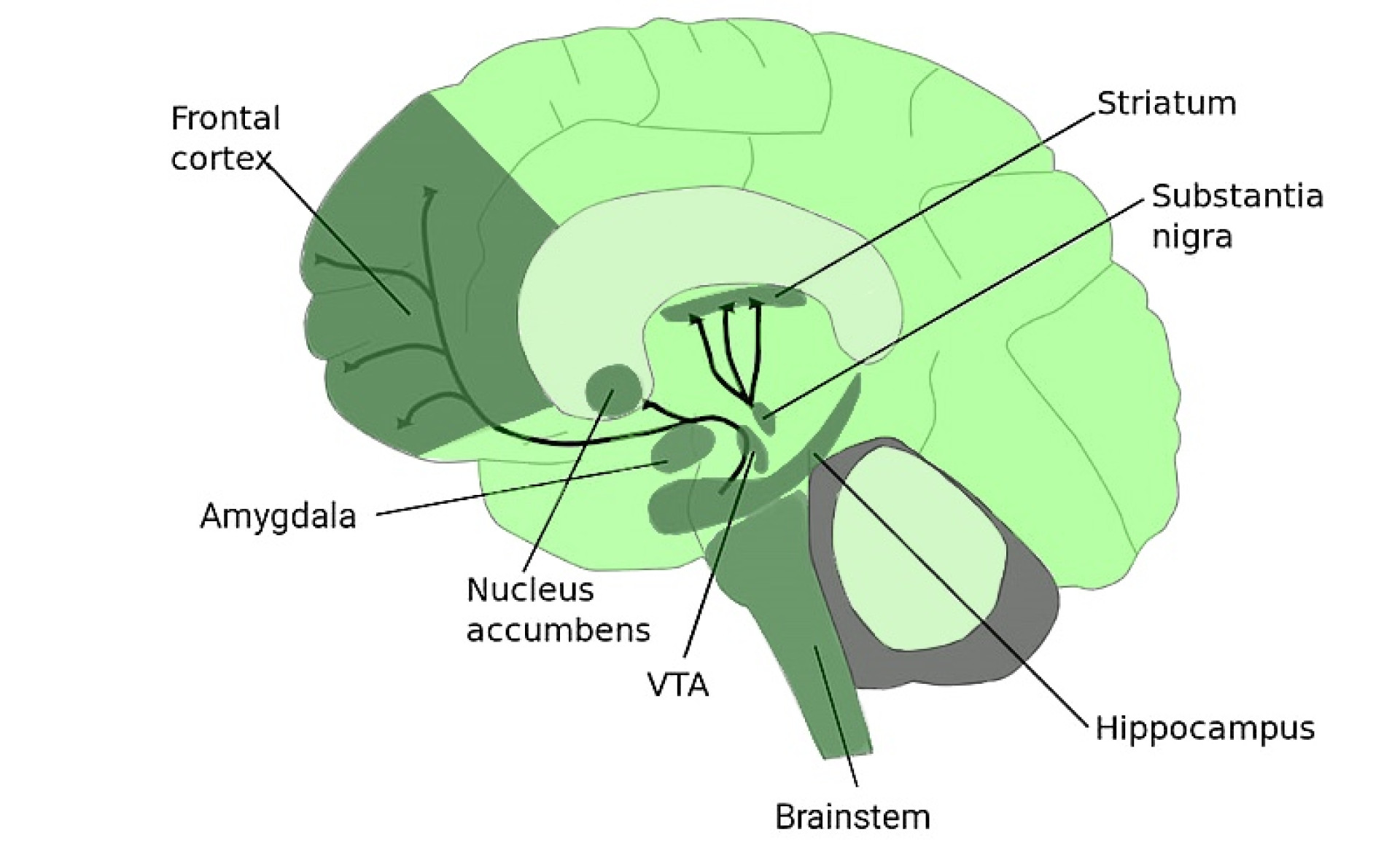

When we watch a Reel, a Short, or a TikTok, our brain activates a complex reward system that engages one of the oldest neural networks in the human mind: the reward circuit. This system, which has played a crucial role in the survival of our species from an evolutionary standpoint, includes structures like the nucleus accumbens, the ventral tegmental area, and the prefrontal cortex. It is responsible for our ability to seek, obtain, and experience pleasure from things that “gratify” us. The brain’s intrinsic purpose here is to boost positive feelings after performing essential activities like finding food, building social relationships, or succeeding in tasks we might broadly define as “vital.” Today, however, online content exploits this system in ways our brain—evolutionarily speaking—isn’t equipped to handle.

Dopaminergic circuit

Dopaminergic circuit

Simplifying the matter a bit, we can say that every time a video manages to entertain us, our nucleus accumbens releases dopamine, the neurotransmitter responsible for regulating pleasure and motivation. Dopamine, in behavioral terms, reinforces the value of the action that triggered its release, actively pushing us to repeat the experience.

During the passive consumption of short videos, this dynamic is amplified by their structure: they start with an effective visual hook that immediately grabs our attention; they unfold in just a few seconds, resolving an emotion or curiosity quickly and compellingly; and, as soon as they end, they leave us ready to jump to the next piece of content with a simple swipe of a finger. This highly engaging mechanism creates a continuous cycle of instant gratification, where each video delivers a small dose of dopamine that keeps us—quite literally—hooked to the platform.

Dopamine formula

Dopamine formula

There’s another aspect to keep in mind: it’s not just the momentary pleasure that makes this content so captivating, but also (and perhaps even more so) the anticipation of what comes next. Think of that Campari commercial with the handsome guy in Victorian attire asking, “And what if the anticipation of pleasure were itself the pleasure?” Well, that’s exactly the principle at play. Every time we scroll to the next video, our brain enters a state of active anticipation, preparing itself to receive a new reward. The very act of scrolling becomes enjoyable in itself because it fuels curiosity and stimulates the brain’s reward circuit.

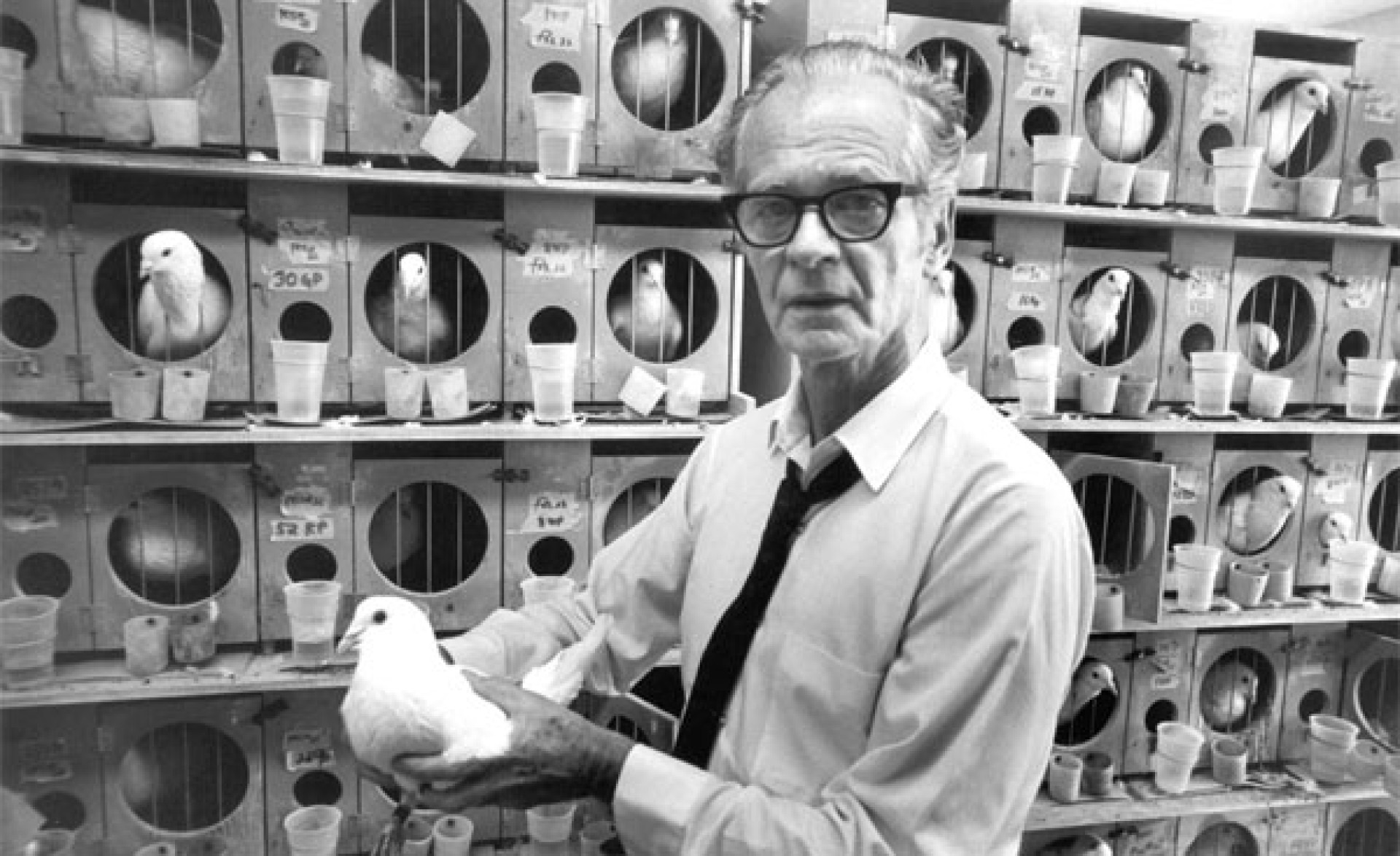

But that’s not all: anyone with a basic understanding of psychology might already see a link to the concept of intermittent reinforcement, studied by B.F. Skinner in his experiments on operant conditioning. Put simply, unpredictable rewards—those that arrive at relatively random intervals—are far more effective at creating addiction than constant, predictable ones.

Think about a scrolling session on social media: not every video is going to be incredibly entertaining or stimulating, and yet the possibility that the next one might be “the right one” keeps us swiping. Then, every once in a while, a particularly satisfying video rewards our effort, reinforcing the behavior.

B.F. Skinner

B.F. Skinner

A nearly identical mechanism, for comparison, is used in slot machines, where the prospect of winning keeps players glued for hours (while, as is tragically well known, emptying their pockets). On social media, scrolling becomes a form of “mental gambling,” where the reward comes in the form of entertainment, emotional response, or satisfied curiosity.

This subtle link to gambling addiction brings us to the decidedly darker side of the cognitive-behavioral dynamics associated with compulsive digital content consumption. Perpetual scrolling causes the brain to develop a form of tolerance known as dopamine downregulation. After receiving quick, frequent micro-rewards, dopamine receptors become less sensitive: in simple terms, we need increasingly intense stimuli to feel the same pleasure we experienced initially. This partially explains why activities that require more time and effort—like reading a book, watching a movie, or contemplating a work of art—tend to feel less rewarding compared to consuming short videos. Our brain is, quite literally, getting accustomed to such a high level of stimulation that everything else, by comparison, seems boring.

The phenomenon of tolerance also has a direct impact on our ability to experience lasting satisfaction. As I mentioned earlier, each scrolling cycle becomes less fulfilling than the last, generating a form of chronic dissatisfaction: even when we encounter enjoyable content, the positive feeling is almost always fleeting because the brain is already primed to receive the next stimulus.

This state mirrors what is seen in substance addictions, where tolerance to a psychoactive compound drives individuals to expose themselves to progressively higher doses to fill a void that only seems to grow more and more. Of course, the compulsive consumption of digital content is not comparable—fortunately, I’d say—to alcohol, drug, or gambling addiction in terms of psychophysical damage. Still, the sensation encapsulated by the term Brain Rot is a real and tangible side effect of a relatively new dynamic.

Ludopatia

Ludopatia

The mental fatigue that accompanies a long scrolling session, then, is the result of a heavy cognitive and sensory overload. Each digital content piece requires the brain to process visual, auditory, and emotional stimuli in rapid succession, consuming vast amounts of cognitive energy. Unlike slower, more focused activities, such as reading, drawing, or writing, the consumption of short videos stimulates constant shifts in attention, alongside rapid processing of information. After a certain period, our brain becomes “saturated,” leading to a sense of emptiness and fatigue, despite the body having made no physical effort.

Moreover, the hyper-stimulating nature of fragmented digital content inhibits the relaxation of default neural networks, the same ones that activate during moments of calm or introspection. These are crucial circuits for mental recovery, as they allow the brain to reorganize and consolidate information. However, if the brain never has the time to “switch off,” the result is a fatigue similar to what one feels after a day of intense work, yet lacking the natural sense of fulfillment that accompanies efforts yielding a tangible result. It may sound a bit neomarxist, but Brain Rot is, in effect, a contemporary form of alienation.

So how do we break free from this? It’s not that simple. And it’s not enough to say, “delete your social media.” Because while it’s true that most online content functions like a digital drug, we can’t deny that there are also invaluable pieces of content out there, capable of enriching our view of the world with fresh, original, and interesting perspectives. In my view, the only solution is to work through subtraction. Eliminate the superfluous, limit scrolling for its own sake, identify a few interesting sources (or seek them out, but in a more active and mindful way), and invest energy in consuming high-quality content. We need to make an effort to dive deeper, especially. Because the best Shorts, Reels, and TikToks do this: they spark a curiosity. The worst thing we can do, when engaging with these tempting and seductive contents, is think that they can “solve” the topic they address (and I’m already talking about informative, educational, or artistic content of value). Let’s take them for what they are: little postcards from infinite universes waiting to be explored. But let’s take them as an invitation, not as an all-inclusive guided tour.

At the same time, and I say this again without fear of falling into empty rhetoric, let’s try rediscovering the value of art. It’s very simple, after all: while short videos offer immediate, shallow gratification, art creates an experience of immersion, reflection, and deep connection. We’re not talking about a merely aesthetic contrast, but also—and above all—a neuropsychological one. Art requires our brain to slow down, contemplate, and focus. All things that compulsive digital content consumption, as we’ve seen, tends to suppress. In contrast, during the contemplation of a work of art, our brain activates a very complex process that involves areas responsible for sustained attention, memory, and symbolic understanding, such as the prefrontal cortex and the anterior cingulate gyrus.

This is a form of mental “training” that undoubtedly requires an initial effort, but it rewards us with a sense of satisfaction and completeness that is impossible to achieve through passive consumption. It’s similar to what happens during meditation or intense physical activity, all actions capable of restoring neurochemical balance, reducing stress, and improving overall well-being. And this parallel with physical exercise becomes especially evident in the post-contemplation satisfaction. Just like a challenging run leaves the body tired but revitalized, engaging with a work of art may initially seem cognitively “costly.” However, dedicating time to art allows us to access a deeper level of contemplation and appreciation – both intellectually and emotionally – generating a sense of fulfillment that lingers long in the mind.

In the end, we need to slow down. Subtract, eliminate the superfluous. Minimize the “digital noise” and reclaim small moments of silence and contemplation. Easier said than done, I know. But I want to revisit the concept I mentioned earlier: digital content, the truly valuable kind, should invite us to find time to delve deeper, contemplate, and reflect. In fact, I’ll rephrase: “finding” time is a deeply misleading term. We already have the time – despite living in the constant illusion that we don’t – we simply throw it away. Try opening Instagram and checking your daily usage time for the app: all the data is there, day by day, usually for the past week. For me, it’s always a surprise to discover how many minutes—sometimes hours—I spend on the platform. There it is, Brain Rot. And I don’t want to come off as pure and righteous in a sick world. Everyone uses social media, and there’s so much, so much interesting stuff there: I myself (like any other contributor to Spaghetti Boost, by extension) hope to create valuable content. Again, the solution is to minimize the background noise. To avoid becoming deafened. And, above all, with a brain “rotting”.

Creative, teacher and expert in visual culture, Alessandro Carnevale has worked on TV for several years and has exhibited his works all over the world. In 2020, the Business School of Il Sole 24 Ore included him among the five best Italian content creators in the artistic field: on social media he deals with cultural dissemination, covering a wide spectrum of disciplines, including the psychology of perception, semiotics visual, aesthetic philosophy and contemporary art. He has collaborated with various newspapers, published essays and written a series of graphic novels together with the theoretical physicist Davide De Biasio; he is the artistic director of an open-air museum. Today, as a consultant, he works in the world of communication, training and education.