From the Golden Ratio to Social Intelligence

The invisible impact of art

Soap, worn sheets, a metal spoon: Jesse Krimes had nothing else. He worked in the half-light, late at night, moving slowly to make noise. Under his mattress he had hidden hundreds of newspaper clippings: he collected faces, mostly. Mug shots that accompanied crime news articles. Or landscapes, images of a world that existed only beyond the bars and concrete walls that surrounded him for more than a year. During the day he would steal some other inmate's hair gel. Occasionally they would catch him, but when he explained what he was in for, they would take him for a fool and leave him alone. At night, when everyone else was asleep, he would press the pictures onto the gel-covered soapsuds with a spoon. Slowly the pictures would transfer onto the whitish surface, leaving an ethereal, almost invisible trace. But beautiful, in its way.

After a few months of experimenting, he decided to switch to sheets. The risk of being discovered increased, and with it the time needed to imprint the images from the cutouts onto the fabric. Half an hour per cutout, sometimes more. The new ‘canvases’ were bulkier, more and more difficult to hide. But Jesse was bold. He had found a couple of guards willing to help him, perhaps out of pity, perhaps to share a memorable feat. Perhaps, simply, to kill the boredom. Over the course of a year, he managed to smuggle dozens of canvases to the outside world, to collect them and assemble them together into a single work, once he had left the penitentiary. This is how the monumental work Apokaluptein:16389067 was created, consisting of 39 panels made on sheets provided by the prison. The title comes from the Greek word ‘apokaluptein’, which literally means ‘to reveal’, and Krimes' identification number in the Federal Bureau of Prisons, 16389067.

Apokaluptein:16389067 © Jesse Krimes

Apokaluptein:16389067 © Jesse Krimes

Apokaluptein:16389067 was exhibited in several venues, including the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University, where it was presented as a powerful critique of the commodity culture that fuels criminal behaviour and the system that punishes transgression without seeking reform. Today, Krimes - yes, that is his real surname - is a firmly established international artist: after serving his sentence for drug possession and dealing, he was able to exhibit his work in such prestigious institutions as MoMA PS1, the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Palais de Tokyo.

Apokaluptein:16389067, MoMA PS1 Installation, © Jesse Krimes

Apokaluptein:16389067, MoMA PS1 Installation, © Jesse Krimes

His is just one of the many stories of convicts who have found the path to redemption in art. Jimmy Boyle, above all, is perhaps the artist with the world's most notorious criminal past: born and raised in Gorbals, one of Glasgow's most violent neighbourhoods, as a young man he earned the grim reputation of ‘Scotland's most feared gangster’. Sentenced to life imprisonment for murder in 1967, imprisonment within the walls of Barlinnie prison inexorably marked his life. For the better, one might say. In the claustrophobic space of isolation - in which he was often confined - he began to explore creativity as a mental and spiritual escape route. Thanks to rehabilitation programmes and the support of some progressive educators, he was offered access to artistic materials. After an initial phase of rejection, Boyle began sculpting using the simplest tools: pieces of wood, metal fragments and scraps salvaged from prison warehouses. The crude, improvised materials reflected the rawness of his experience, but under his hands they were transformed - paradoxically - into sculptures that spoke of humanity, pain and aspirations for freedom.

Jimmy Boyle sculpture

Jimmy Boyle sculpture

His works convey a perfect synthesis of suffering and desire for redemption. Each creation seems to show the vulnerable side of a man who, throughout his life, had been defined only by violence. Boyle sculpts distorted human figures, dramatic expressions that evoke intense introspection, in which an echo of hope reverberates. Despite the physical and material limitations of prison, his art gradually gained the attention of critics and the outside public. After his release from prison in the 1980s, Jimmy continued to explore and develop his art, participating in countless exhibitions and promoting prison reform as an activist. His sculptures have become symbols of a path to redemption - an intimate testimony to the power of art that allows anyone to leave a trace of ‘beauty’, transforming - why not - an entire life journey.

Jimmy Boyle sculpture

Jimmy Boyle sculpture

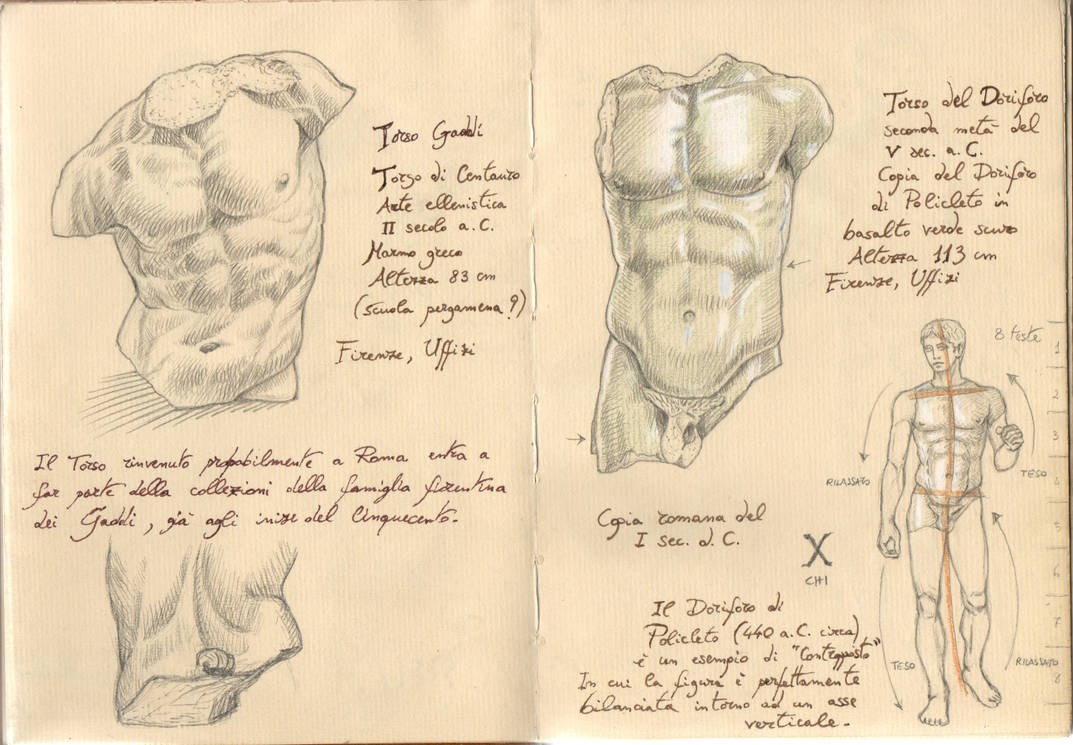

Now, there are countless virtuous examples demonstrating the positive impact of artistic culture within complex social fabric. And this, paradoxically, may have a somewhat ‘biological’ origin. Let me explain: in 2007, Di Dio and Rizzolatti, two Italian neuroscientists, conducted a study that brought Polyclitus' Doriphorus, the symbol of classical beauty, from museums to research laboratories. The sculpture, famous for its perfect proportions based on the golden ratio, was used to investigate the perception of ‘objective’ beauty in the human brain. The participants - 14 people with no specific artistic expertise - were monitored with functional magnetic resonance imaging while observing three different images of the sculpture: one was the original, while the remaining two had been modified to artificially alter the proportions of the figure.

The results showed that viewing the Doriphorus in its original form activated the frontal lobes - especially the ventromedial area - with high intensity. When the participants viewed the distorted version, however, the reactions in these areas were almost imperceptible, while the activation of the insula and, albeit weakly, also the premotor areas of the frontal lobe, anterior to the primary motor cortex, were evident. This suggests that the brain ‘innately’ recognises and responds positively to visual stimuli that follow harmonious proportions, regardless of the participants' cultural background.

In other words, the beauty of the Doriphorus is also perceived as intrinsically pleasing and ‘correct’ on a neurological level. For the sake of completeness, it is only fair to specify that the experiment showed that the innate recognition of proportionate shapes does not necessarily coincide with an aesthetic preference. When participants were asked to choose the version they preferred, in fact, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), a brain area involved in decision-making, critical evaluation and inhibition of immediate emotional responses, was activated in their brains. In essence, when the participants had to make a conscious judgement on the work, the activation of the DLPFC reflects the cognitive and rational analysis of aesthetics, which goes beyond the simple recognition of the internal harmony of forms: when faced with a specific request, therefore, higher cognitive processes come into play that modulate the aesthetic experience in an extremely complex way.

Human brain diagram

Human brain diagram

The most fascinating aspect, however, is another. During the observation of the deliberately disproportionate works, as I mentioned, there was a weak - but not insignificant - activation of the premotor areas in the brains of the experiment participants. It is possible that by visually analysing anomalous or ‘wrong’ proportions, the brain attempts to mentally compensate or ‘correct’ the figure by recalling motor simulation mechanisms. The premotor areas, in fact, are involved in movement planning, but at the same time play a role in the recognition of familiar forms: their activation could therefore indicate a sort of ‘effort’ of the brain in processing images that are incongruent with perceptual expectations.

But that's not all: the activation of the premotor areas also reflects an instinctive response that prepares the body for fight or flight, supported by the production of neuroactive molecules that determine and stimulate a ‘violent’ response. Conversely, the observation of harmonic images predisposes the brain to the higher cognitive functions of creativity and abstract thought. Correlating the results of Rizzolatti and Di Dio's study with the analysis of medical cases of subjects who suffered brain lesions in the areas predisposed to recognising ‘beauty’ (above all, the inferior orbitofrontal cortex), in which aggressive and antisocial behaviour was found to occur, we can deduce that the observation of harmonious images contributes to some extent to operating an inhibitory control on the brain areas that trigger violent reactions.

In 2017, scientists from the School Of Social Policy & Practice at the University of Pennsylvania published the results of a significant study that examined the impact of arts and cultural activities on low-income neighbourhoods in large American cities, focusing in particular on the most problematic areas of New York City. The project involved a network of academic researchers, local cultural organisations, public administrations and educational institutions, collaborating with actors such as the New York City Department of Education and non-profit organisations committed to promoting the arts as a tool for social change. The objective was to assess whether and how the presence of cultural activities in specific communities could influence socio-economic factors such as crime rates and school success.

SIAP used a methodology based on the analysis of data collected in neighbourhoods with varying levels of participation in arts activities. The analysis integrated socio-demographic data with information on crime, school drop-out rates and academic achievement. Among the main findings of the study, it was found that areas with a more vibrant arts scene tended to show a significant reduction in crime rates: in three years, homicides were reduced by 14%; violent crimes by 18%. Not only that: In terms of education, areas with a strong presence of cultural initiatives boasted a 10% increase in the number of students achieving significantly better results in exams in literature and English language, art and mathematics. It seems quite clear, therefore, that there is a close connection between exposure to and active participation in artistic activities, aesthetic contemplation and a general improvement in the socio-cultural fabric in which these practices are most prevalent. Here: to sum up what has been discussed so far, I want to tell you the incredible story of Phineas Gage.

Phineas Gage

Phineas Gage

It is the mid-19th century. Gage is a foreman of railway workers in Vermont: everyone knows him as a competent, respectable and socially well-connected man. His life changes dramatically on 13 September 1848, when an accidental explosion during a blasting operation causes an iron bar about three feet long and three inches in diameter to shoot through his skull. The bar perforates the left zygomatic bone, passes through the left frontal lobe and exits through the top of the head.

Miraculously, Gage survives the accident and does not lose consciousness. The doctors are amazed by his ability to speak and move immediately after the trauma - but as time passes, drastic changes in his personality and behaviour emerge. Phineas becomes short-tempered, impulsive, incapable of making long-term plans and of taking any responsibility for his actions, which increasingly border on the acceptable.

Simulated Connectivity Damage of Phineas Gage

Simulated Connectivity Damage of Phineas Gage

His case demonstrated for the first time that there are areas of the brain that specifically regulate personality and social behaviour. Prior to that, relatively little was known about the role of different brain regions: damage to the frontal lobe, in particular the prefrontal and ventro medial areas, made it clear that these parts of the brain are crucial for impulse control, decision-making and emotion regulation. Much more recently, neuroscientists Hanna and Antonio Damasio studied seven patients with brain impairments similar to Phineas Cage's. Expanding the scope of their investigation, they found that none of them showed any conscious or unconscious reaction to viewing pleasant images (even artistic ones, of course) or, conversely, to viewing horrific images.

The ability to respond to an aesthetic stimulus thus seems closely related to the ability to develop any kind of ‘social emotion’. If we still have any doubts about the value of art in our contemporary world, it would be useful to reflect on these borderline cases - which, even in their absolute exceptionality, manage to shed light on the deepest neurological mechanisms that unite, for better or worse, all human beings.

Cover image: Doriphoros of Polyclitus

Creative, teacher and expert in visual culture, Alessandro Carnevale has worked on TV for several years and has exhibited his works all over the world. In 2020, the Business School of Il Sole 24 Ore included him among the five best Italian content creators in the artistic field: on social media he deals with cultural dissemination, covering a wide spectrum of disciplines, including the psychology of perception, semiotics visual, aesthetic philosophy and contemporary art. He has collaborated with various newspapers, published essays and written a series of graphic novels together with the theoretical physicist Davide De Biasio; he is the artistic director of an open-air museum. Today, as a consultant, he works in the world of communication, training and education.