Everyday Lusaka Gallery: The Politics and Poetics of the Quotidian

Art of the quotidian between memory, space and resistance

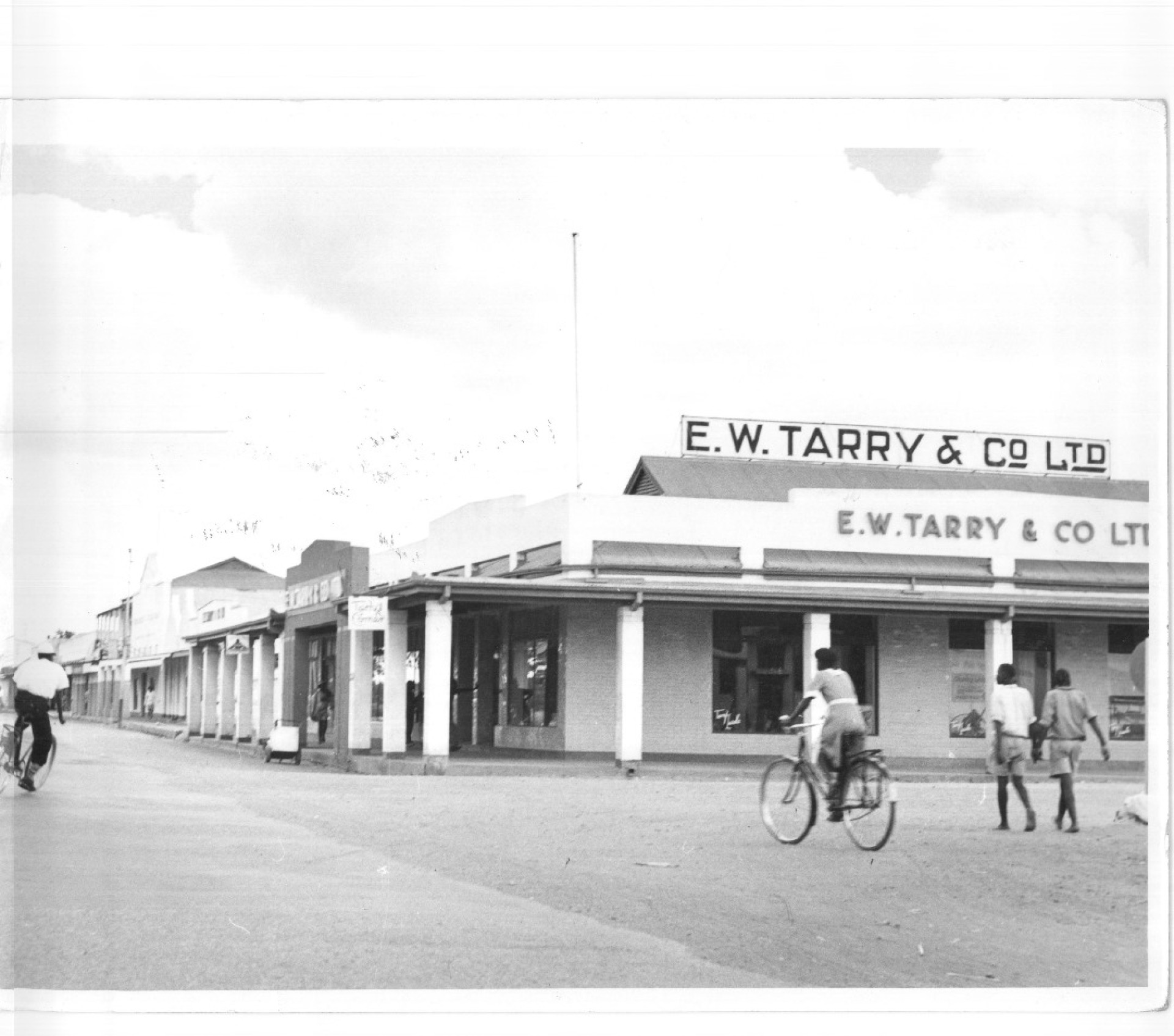

Nestled in the E.W. Tarry building just off Cairo Road in Lusaka’s Central Business District stands the now-yellow-pillared home of Everyday Lusaka Gallery. Founded by Indian-Zambian curator and archivist Sana Ginwalla, the gallery has become one of several flourishing artistic spaces redefining how Zambia’s capital city sees itself—and how it is seen by others. As the Zambian contemporary art scene continues to morph and evolve—marked by a growing number of independent spaces, curatorial initiatives, and cross-disciplinary practices—Everyday Lusaka contributes a perspective attuned to the textures of ‘everyday’ life. The gallery leans into the subtle, drawing critical attention to what is often overlooked yet deeply formative in how we live and relate. This centering of overlooked moments and quotidian beauty through visual arts and critical exhibition-making is embedded in the practice of the gallery’s founder and head curator. For Ginwalla, visual culture is a living archive—a way to ask questions rather than assert answers. Her curatorial practice is shaped by a deep sensitivity to what it means to belong, to remember, and to imagine otherwise.

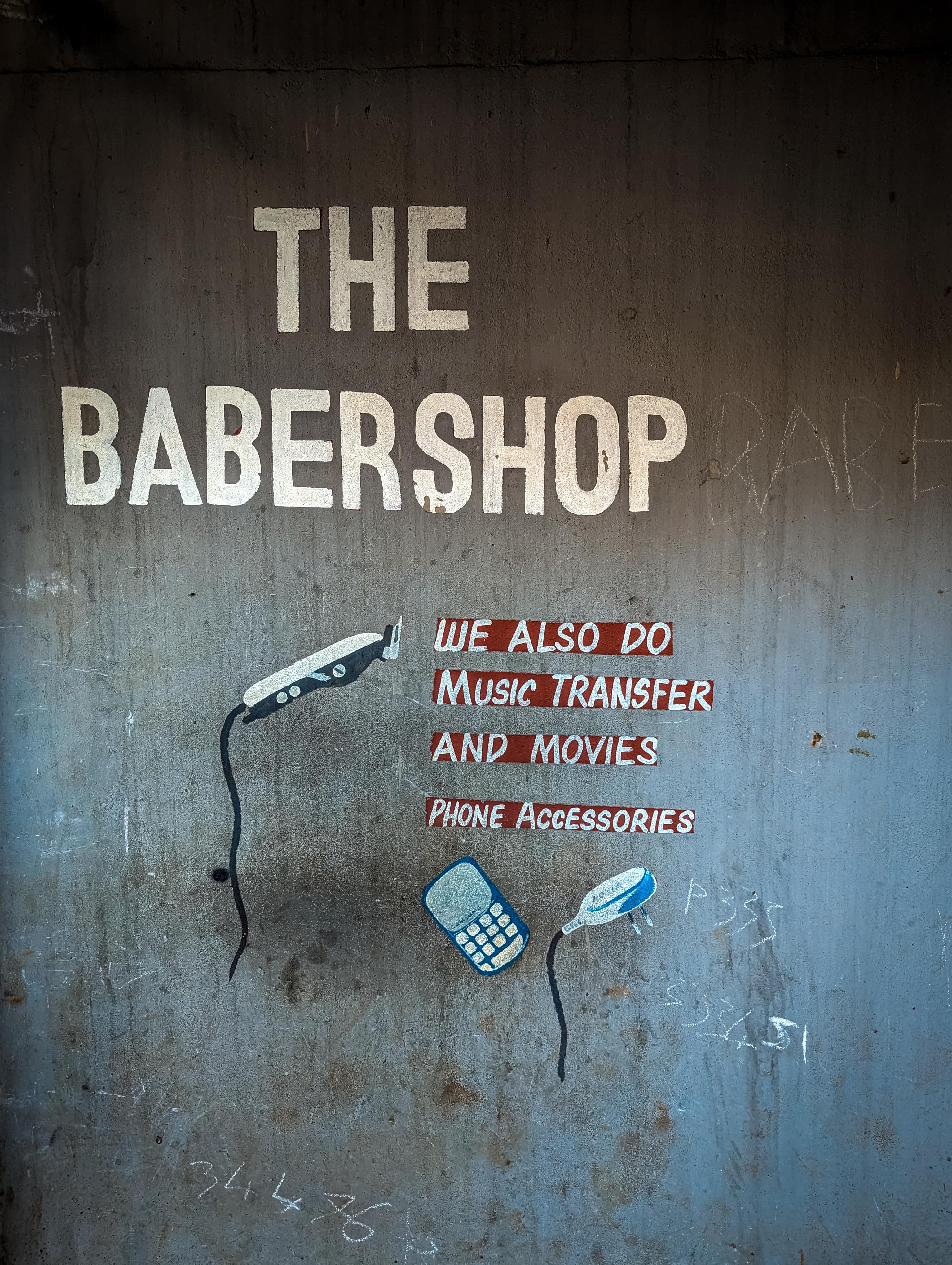

Everyday Lusaka began not as a gallery, but as an evolving photographic archive capturing the city’s textures, signage, infrastructure and fleeting moments of daily life. At its core was a desire to center images—and by extension, stories—often undervalued in contemporary image-making in Zambia. What began as a personal and observational practice soon became communal, inviting others to view the city through a similarly attentive lens. In documenting the ordinary, the Everyday Lusaka community reoriented how shared moments in the city are perceived: a weathered wall bearing decades of paint, a handwritten sign taped to a wooden pole, the geometry of a quasi-brutalist skyline. This distinct visual language laid the foundation for what would become the Everyday Lusaka Gallery. The transition from digital project to physical space was not simply one of location, but of experience—tactile, dialogic, and alive. The gallery opened as a site where these everyday observations could be held, expanded upon, and shared in new forms. It reflects a belief that the visual is not just about aesthetics, but about how we remember, relate, and make sense of place.

By situating itself in Lusaka’s Central Business District—rather than in the more affluent or often inaccessible neighborhoods where many of the city’s art spaces are located—Everyday Lusaka challenges the spatial politics of exhibition-making. Its presence on Cairo Road dissolves many of the formal and informal barriers that distance people from art, positioning the gallery within the city’s daily rhythm rather than apart from it. In doing so, it gestures toward the legacy of Mpapa Gallery (1978–2002)—Zambia’s first independent art space—also located in the CBD and similarly attuned to the nuances of the everyday. Reaffirming this spatial commitment, Ginwalla writes: “In opening our gallery in a seemingly inconvenient or unideal space, Everyday Lusaka contests the idea of where art would conventionally be encountered in the city. Daily, the energy, sounds and people of Lusaka and its streets permeate into the gallery space. This is a space where all kinds of people walking the streets, looking for and selling various items, will stumble upon art. After all, if art is a universal language, should it not be accessed by everybody?”

E.W Tarry Building in 1950, Photograph Courtesy of National Archives of Zambia.

E.W Tarry Building in 1950, Photograph Courtesy of National Archives of Zambia.

The gallery offers a space for experimentation and critical engagement—attuned to the layered realities of the city and those who move through it. These nuances are charted in its exhibition and programming catalogue, which deepens the gallery’s curatorial inquiries, often situating the local within broader continental and global questions of movement, memory, and belonging. One such inquiry unfolds in Ulendo: Searching for Belonging, a solo exhibition by visual artist Daudi Yves. Here, personal and collective reflections converge around life in Lusaka—and Zambia more broadly—through the perspective of forcibly displaced communities. As Amouraé Bhola-Chin writes in the exhibition catalogue: “Emerging in an era marked by conflict, genocide, and widespread social upheaval, Daudi M. Yves’ debut solo brings our attention to forcibly displaced communities in Zambia. With roots stemming from Congo, Daudi M. Yves pays tribute to his onwards journey that caused him and his loved ones to find refuge in Zambia.”

In the piece Long Live, Yves uses oil and charcoal on sunflower-yellow fabric to render an image of Patrice Lumumba, the first Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of Congo, anchored against a Lusaka street sign bearing his name. Known for his uncompromising anti-imperialist stance and pan-African politics, Lumumba—like many radical freedom fighters across the continent—was assassinated in 1961. His death marked a turning point in the political and humanitarian instability of the DRC, a crisis that continues to unfold. Today, Zambia hosts over 102,000 forcibly displaced people, the majority from the DRC—making Yves’ reflections both deeply personal and urgently relevant. The artist reflects: “Wars and conflicts are constant... [But] archiving the time, and existing in it, gives voice to those like me. Art, in itself, is a service.” Yves’ words offer a critical entry point into understanding how the work navigates both personal testimony and historical witnessing. Long Live is not merely a tribute to Lumumba’s legacy, but a layered act of remembrance that folds together past and present, public iconography and private loss. The choice of medium—fabric marked by oil and charcoal—evokes both the fragility and resilience of memory. The sunflower-yellow cloth becomes a tactile register of warmth, longing, and resistance. It holds the image of a leader who once stood for unity and liberation, now re-situated in a city that shelters those fleeing the very consequences of such ideals being denied.

In bringing Lumumba into Lusaka’s urban landscape, Yves collapses colonial conceptions of geographical and temporal boundaries, inviting viewers to consider the ways in which coloniality shapes contemporary experiences of exile, identity, and home. The road sign bearing Lumumba’s name is not incidental—it is a signifier of how the city carries traces of other struggles, other dreams. Having been one of the key members of the anti-colonial Front Line States coalition, which included Angola, Botswana, Lesotho, Mozambique, Tanzania and Zimbabwe, Zambia was committed to hosting and supporting liberation movements across the region. Lusaka became home to a number of liberation movements in exile, assuming an active role in cross-border solidarity. Hinged upon its history as a catalyst and supporter for many of the liberation movements across the continent, the infrastructure of the city reflects its position as a mediator state. A number of roads bare the names of radical freedom fighters other than Lumumba, such as Dedan Kimathi, a Kenyan political thinker and leader of the Kenya Land and Freedom Army during the Mau Mau Uprising (1952–1960) and Thabo Mbeki a politician who served as the president of the African National Congress (1997–2007) and president of South Africa (1999–2008).

It is in these layered surfaces, these small but potent visual placements, that Yves constructs a visual language of survival—one that resists erasure and demands recognition. Long Live is one of several works in Ulendo that foregrounds the entanglements between personal histories and continental politics. In this way, Yves’ practice mirrors the gallery’s broader ethos: attentive to the everyday, alert to the forces that structure it and committed to holding space for stories that might otherwise be overlooked. In tracing these stories—of movement, memory, refusal, and becoming—the exhibition affirms the role of contemporary art as a vessel for reimagining shared realities. Through works that are both intimate and expansive, Daudi Yves echoes the gallery’s commitment to holding space for complexity: of displacement and rootedness, loss and resilience, quiet observation and political urgency. In doing so, the exhibition—and the gallery that holds it—makes visible the quieter infrastructures of care, resistance, and imagination that pulse through Lusaka’s streets and beyond.

This commitment to layered and situated storytelling also shapes the gallery’s curatorial approach beyond its physical space in Lusaka. Earlier this year, Everyday Lusaka presented Yves’ Long Live at the India Art Fair in February 2025 as part of the exhibition The Colour Beyond the Colour Line, hosted by Strangers House Gallery in Mumbai. Co-curated by Ginwalla, George Varley, Shamooda Amrelia and Prabhakar Kamble, the presentation expanded on the ideas rooted in Ulendo: Searching for Belonging, extending them into a transcontinental dialogue on displacement, identity, and postcolonial memory. The contributions—ranging from textile to installation—were anchored in multidisciplinary practices that sought to express, in the curator’s words, “a new radical impetus through material, politics, and aesthetics.”

In extending its curatorial work beyond Lusaka, the gallery affirms the urgent need for parallel visions of the future—and alternative ways of being—to collide and converge. Through collaborative spaces and critical exhibition-making across the globe, Everyday Lusaka joins a growing movement that sees contemporary art as a vital site for imagining and building more just, expansive, and interconnected worlds. Here the archive is not static; it breathes, questions, and moves with those who make and inhabit it. Opening up space for reshaping how the future might be felt, imagined, and built—tenderly and together. In this way, Everyday Lusaka challenges dominant hierarchies of knowledge and power—not by positioning itself in opposition, but by quietly carving out alternative ways of seeing, remembering, and building. It centres art not just as representation, but as active participation in the shaping of how histories are held and how futures are imagined.

Cover image: Daudi Yves Gallery shoot

Chona’s current artistic practice is expressed through earth-based alchemy, a process which involves using natural materials such as plants and soils in producing bodies of work which combine ancestral baTonga knowledge and contemporary experimental techniques. Visual poetry is another expression of Chona’s artistic practice. Collages are used as mediums alluding to the intersections of ancestral histories, the present-day and the future of baTonga. Anthropological photographs are often used alongside objects, images and histories of personal accord.Her research and curatorial practice are geared towards the unearthing and exploration of themes of identity, memory, and resistance grounded in a sense of storytelling and healing through alternative mediums. In its entirety Chona’s practice is grounded in the self-composed methodology of Radical Zambezian Reimagination.