Giulia Cenci and the new exhibition "the hollow men" in Florence

Giulia Cenci’s visionary art blends nature, metal, and contemporary unease in her solo exhibition at Palazzo Strozzi.

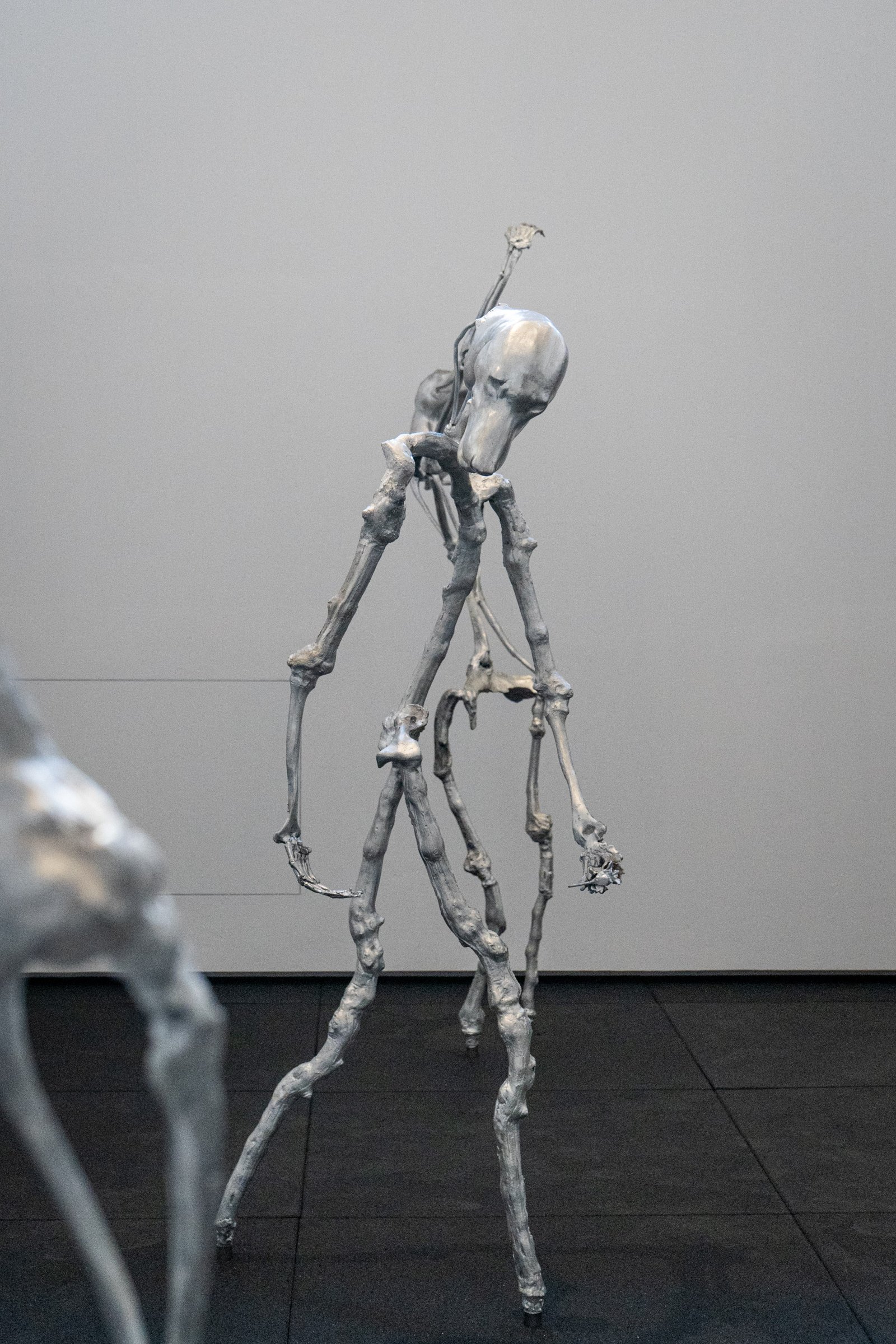

In the countryside of Cortona, Giulia Cenci and her team are at work at the farm she’s transformed into her full-production art studio. A wood-burning stove fires an oven for casting metal, an assistant lights a welding torch, and piles of bones made of silvery aluminum lie in mounds on the floor. Some have already been soldered together to create her phantasmagorical figures — with the tapered heads of wolves atop impossible skeletons that twist and gesture, like the many haunting yet lively figures that populate her solo show at Palazzo Strozzi — now on view until August 31.

In their upright stance, there is something human about the bodies, but the beastly head distorts that perception: the sculptures are both — eliminating the division between animal and human, with flowers bursting randomly from a hand or a hip. “It’s how I see the world,” says Cenci, on video call, in a black tank top with her enormous fluffy white dog Pina at her side, as she strolls through the fields of her art-making farm where she grew up and recently returned, after years in Berlin. “In a place like this, you share life with a series of companions — animals, trees, plants — so it’s not that I’m creating an unrealistic category,” she says. “It’s the division humans make between these categories that I find unrealistic.” Formed from metal scrap reclaimed from industrial scrap, and therefore made of machines, the sculptures further erase category boundaries.

Giulia Cenci. Photography by Giorgio Perottino

Giulia Cenci. Photography by Giorgio Perottino

Even the emotions in the works blur boundaries we usually hold distinct: the sculptures sprightly and full of life, yet also full of morbidity; they might first appear melancholic and slightly unsettling, but then reveal moments of joy — a dance step, a hand held. Is that creature smiling? “Even if they are completely inanimate, just the position of the head or the hand can indicate an almost existential state,” the artist explains.

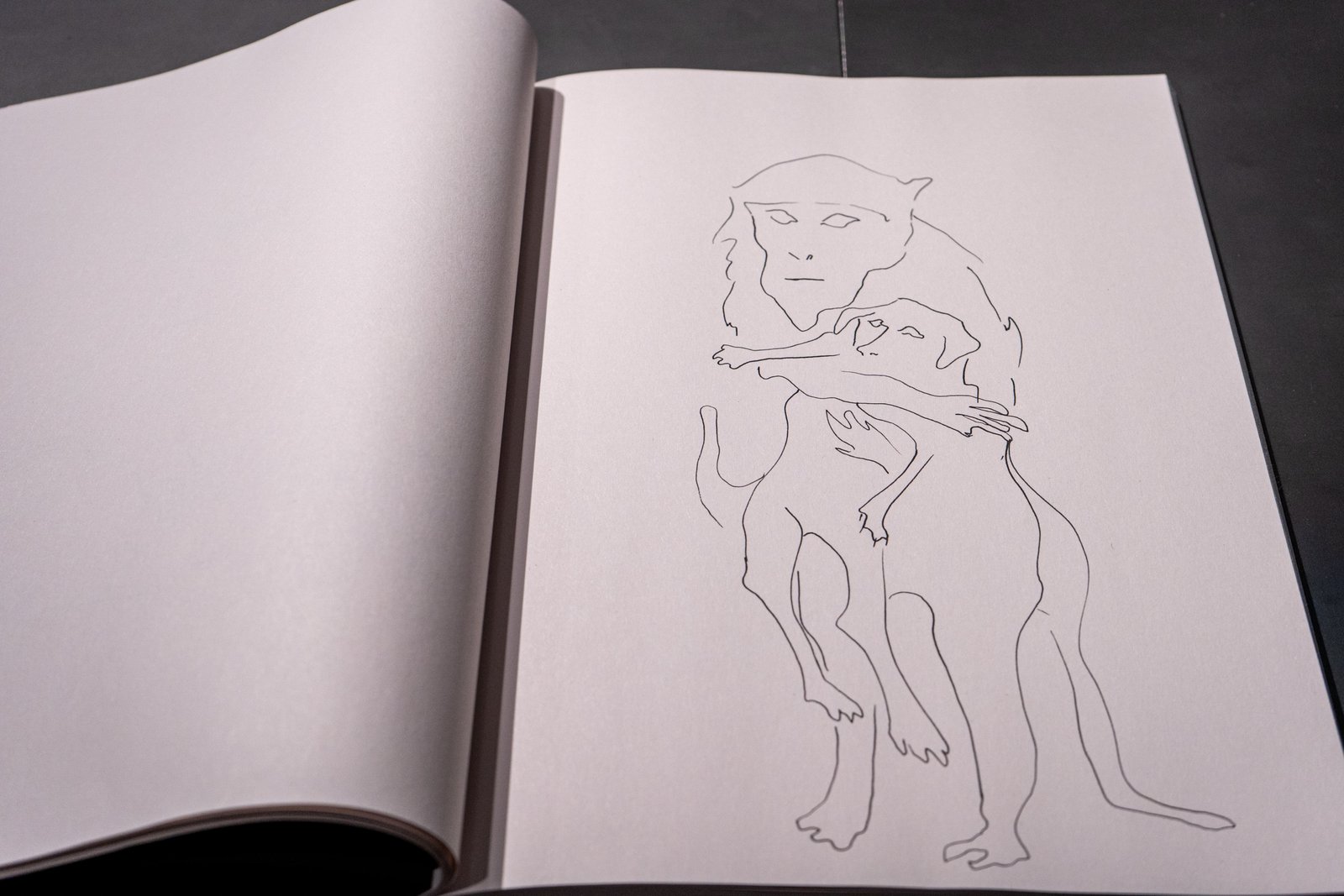

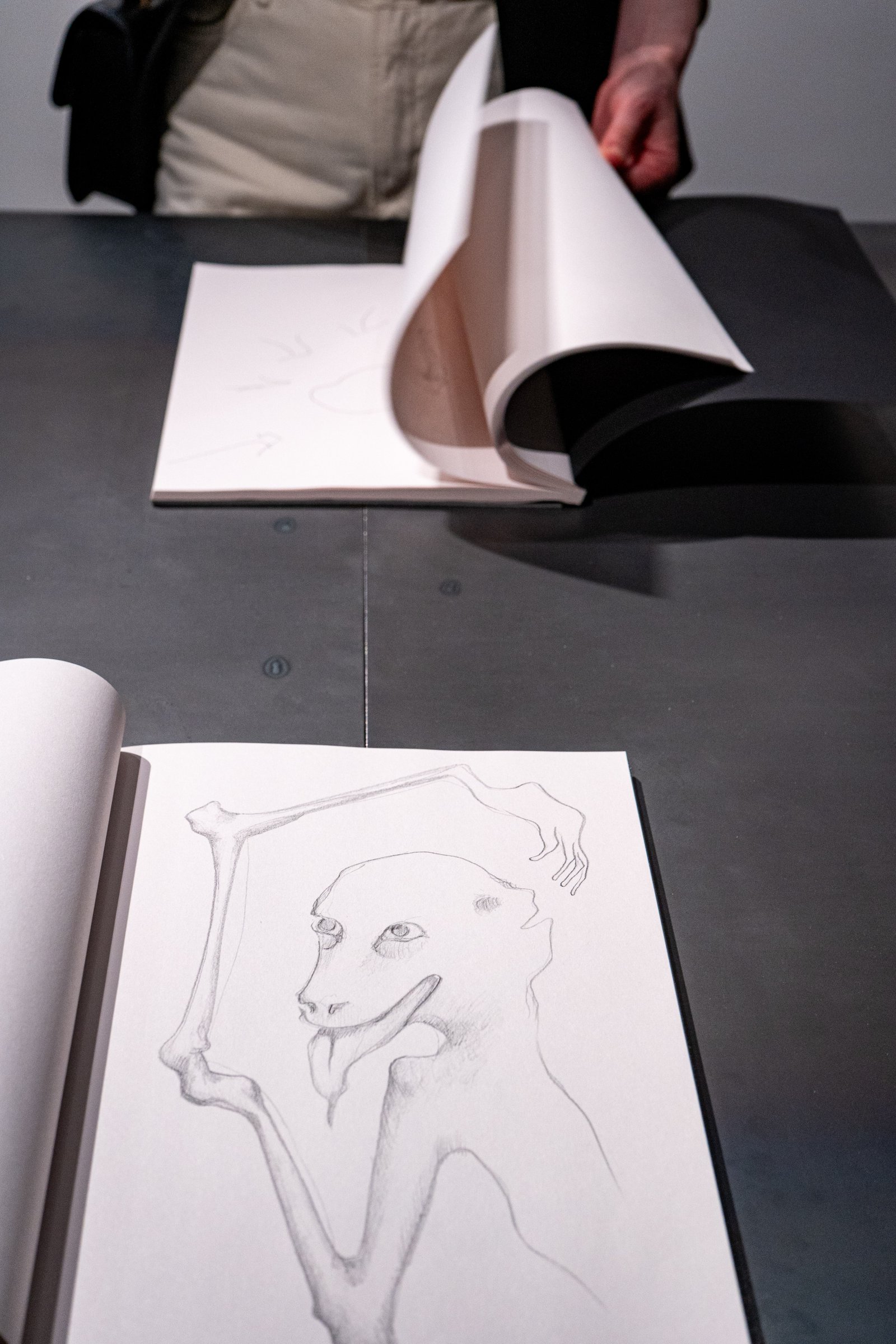

the hollow men, the show by Cenci, is the inaugural exhibition of Project Space — a sign of the rising recognition for Cenci, who was recently signed to the prestigious Massimo de Carlo gallery. Project Space is dedicated to new voices in contemporary art, and set within Florence’s Palazzo dei Strozzi, a museum renowned for its presentations of blockbuster artists — Tracey Emin is currently on view; past artists include Jeff Koons, Anish Kapoor, Anselm Kiefer, Olafur Eliasson, and many more. Where there was once a museum gift shop, today there are two rooms for new art — one large and towering, where Cenci’s hollow men dance and totter around a seemingly infinite screw from the ceiling to the floor of an all-black chessboard; while the other room is small and intimate, where a spectral figure seems to hang on the wall, shrouded in silvery mesh. On a long table, Cenci’s sketchbooks form part of the exhibition, and visitors can flip through perhaps hundreds of her drawings — playful, dark, otherworldly, and always vaguely recalling and blending familiar creatures and bodies: a troubled fantasy domain reflecting our real domain.

Florence, with its tourist masses, its crush of visitors pressing through the Renaissance streets to take pictures of what they already saw on their phones posted by someone else, animates the works with “egomania and tech-fueled self-absorption,” as Cenci says of the crowds — a group united principally by their desire to all do and see and photograph exactly the same things, in stark contrast to the individual searching and groundbreaking imagination that guided Florence to Renaissance breakthroughs in art and thought. the hollow men, a title drawn from a poem by T.S. Eliot, evokes the disorientation and moral blindness that overtook humanity in the wake of World War I’s unthinkable violence — and suggests we’ve never truly stepped off that treadmill of destruction or ceased our habit of blindly following others.

At her farmhouse though, Cenci has created a fertile haven for creativity and craft. Where art today is so often a work imagined and commissioned by the artist, but ever more rarely fabricated by the artist, Cenci believes “art reveals itself in the act of making it. Every step — even every mistake — can spark unexpected results and fresh ideas about what the final work should be.”

She begins her sculptures with sketches and physical piles of castings, which she assembles to form emotions, ideas, and enigmatic representations — but for her, creation doesn’t end with an idea; it deepens through the act of making. “The creation process is much freer, and surpasses the initial idea. The physical act of crafting something with your hands opens up new directions and insights,” she says. “If you instead merely commission a work, you lose that phase of bringing it to life which is so rich in possibilities — and art is really about possibilities.”

Cover image: Giulia Cenci, the hallow men, Project Space, Palazzo Strozzi, Florence, photograph by Pontus Berghe

Laura Rysman is a regular contributor to The New York Times, as well as the Central Italy correspondent for Monocle, and a contributing editor to its sister magazine, Konfekt. An American journalist and a longtime resident of Italy, she writes about the country's art, fashion, and travel scene, with a particular focus on the creativity, craft, and culture of Italy.