Has the Turner Prize suddenly become relevant again?

The Turner Prize, a prestigious annual award celebrating four cutting-edge UK artists, has never shied away from controversy. Past winners have frequently divided public opinion, with examples like Damien Hirst’s shark in formaldehyde and Martin Creed’s empty room where the lights flicked on and off sparking debates about what counts as art. Even Tracey Emin’s ‘My Bed’ - a nominee rather than a winner - provoked headlines questioning its artistic value. Despite the controversy, the Turner Prize got people talking about contemporary art beyond gallery walls and into their living rooms, reaching audiences who might not typically visit museums.

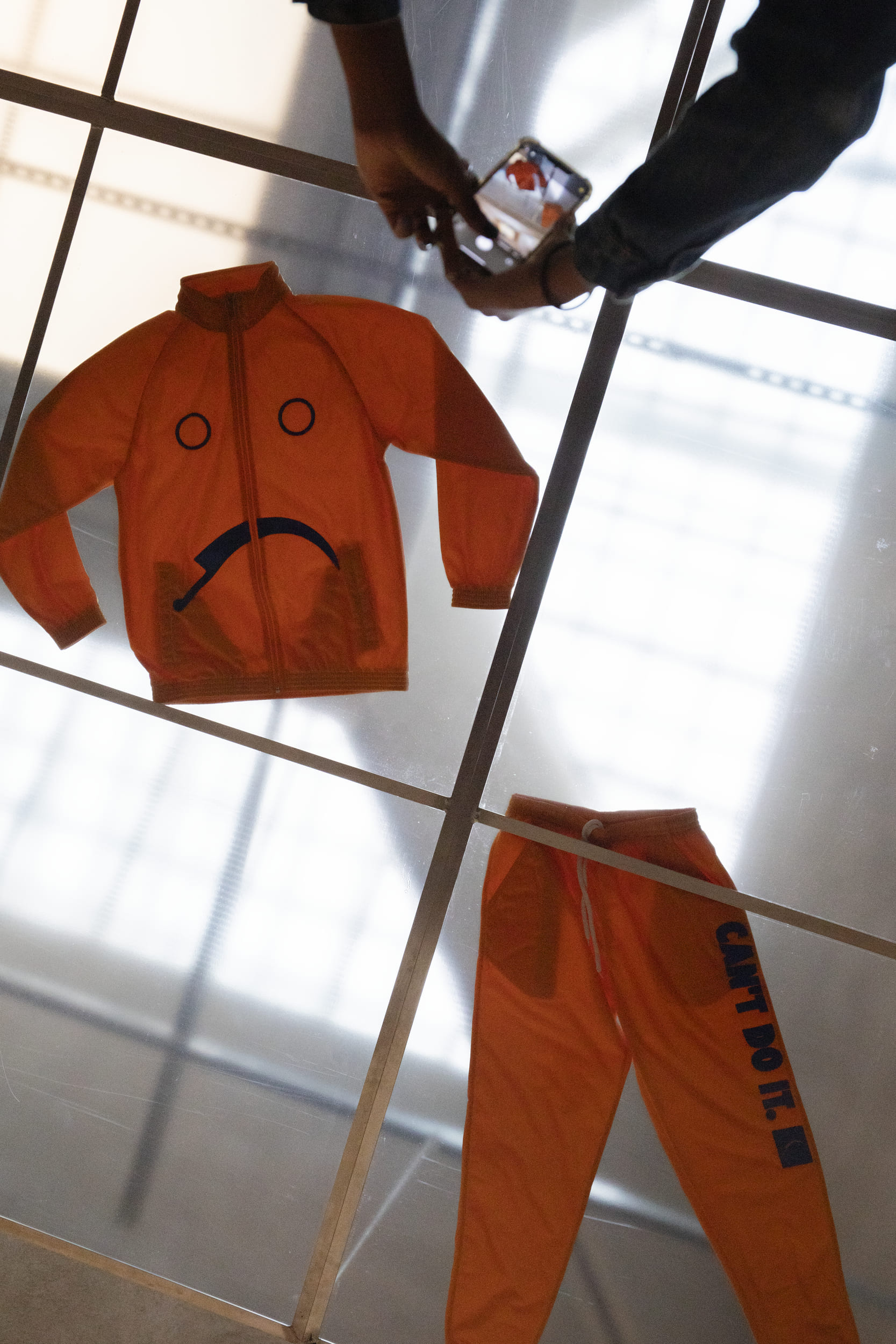

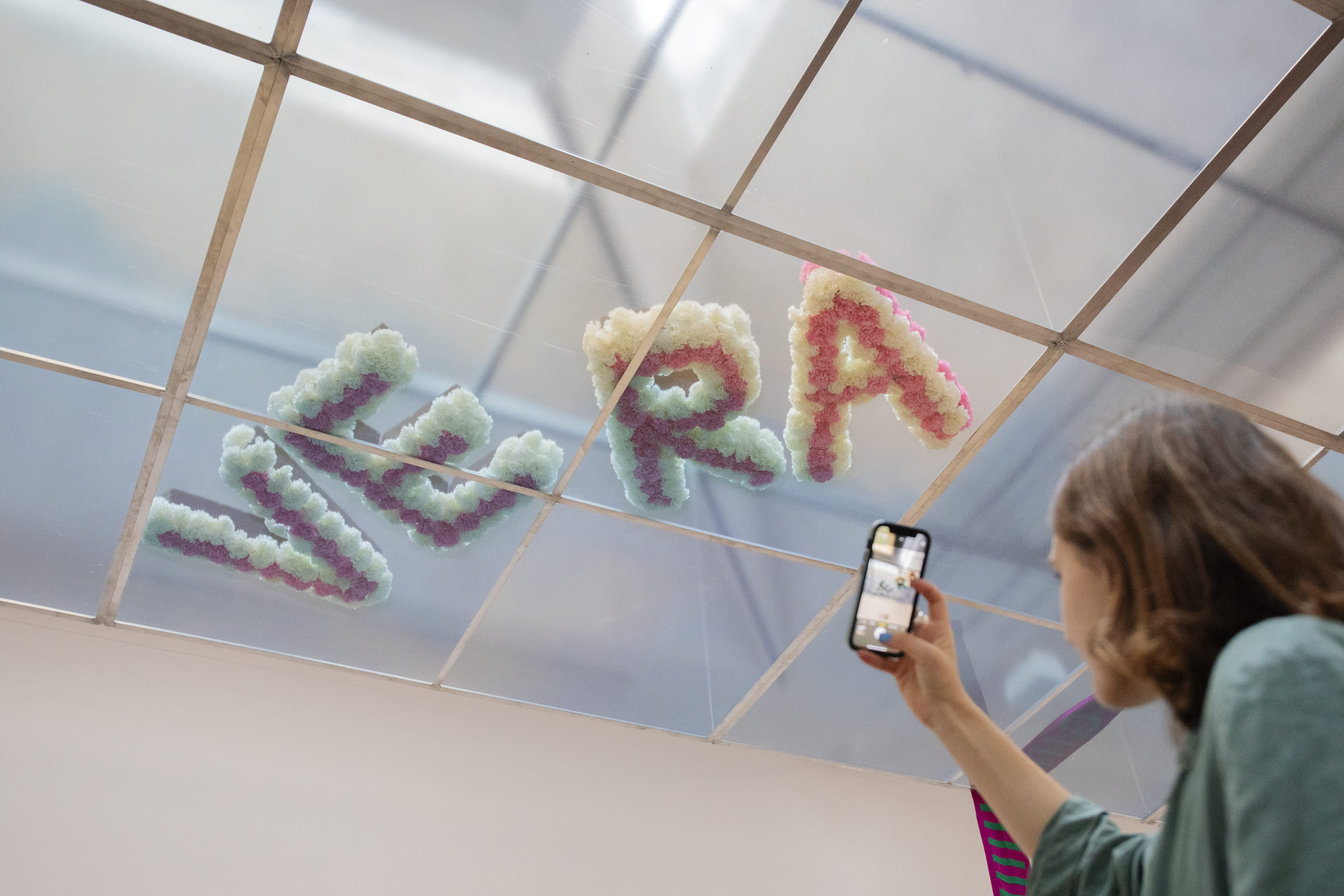

Tate Britain. Photo Rikard Osterlund

Tate Britain. Photo Rikard Osterlund

But has it lost its edge? Is it no longer relevant? Does the public even care anymore?

There’s a strong argument for questioning the Prize’s relevance today given early winners like Anish Kapoor (1991), Antony Gormley (1994), and Steve McQueen (1999) rose to prominence and became household names, celebrated in sculpture and film. Yet after Grayson Perry (2003) and Jeremy Deller (2004), the prize's influence seemed to wane, and recent winners have struggled to leave a lasting impact.

After these came artists who even after winning the prize many years ago failed to make a lasting impact on contemporary art. Does anyone even know what Tomma Abts (2006), Richard Wright (2009), and Duncan Campbell (2014) are up to right now, or remember their work?

While the Turner Prize’s recent significance may be debated, its history is inseparable from the broader transformation of UK contemporary art in the late 90s and early 2000s. Before this period, contemporary art was relatively obscure. The sensationalism of the Young British Artists (YBAs) and the opening of Tate Modern in 2000 revitalised public interest. Today, visiting galleries is much more mainstream in the UK than thirty years ago, though gallery audiences remain predominantly white and middle-class.

This year’s shortlist at Tate Britain marks a refreshing turn. The four shortlisted artists each offer compelling works unified by themes of identity—a timely reflection of their experiences and histories.

Pio Abad takes a deeply researched approach to British colonialism, exploring it through a personal lens - influenced by growing up in the Philippines, a nation colonised by the USA. His work touches on the lingering legacy of empire, reflected in people and places. In one poignant piece, he reimagines a deer-hide map gifted by Native Americans to King James I, portraying it as though it’s bleeding to symbolize colonial devastation. Abad's work underscores that the colonial era isn’t just a distant past but an ongoing influence on our daily lives - what we eat, where we live, and the objects in our museums.

Jasleen Kaur’s installation is more playful as it looks back on memories of growing up in Glasgow with most notably a giant doily thrown over a Ford Escort. Mixing in religious symbolism and everyday items like turmeric it showcases the influence of growing up in Scotland and being of South Asian heritage. It’s a fun presentation but also reflective of the struggle with identity anyone faces when they grow up with two different cultures and must live as what’s often referred to as ‘third culture kids’.

In a more immersive piece, Delaine Le Bas invites viewers into an installation of hanging textiles, creating a space for performance, sound, and costumes. Drawing on her British Roma heritage, Le Bas brings attention to a marginalized community, often stigmatised and overlooked in the art world. Her work embodies the resilience of the Roma people and the reclamation of identity, reminding us that not all minority groups are defined by skin colour.

Claudette Johson is arguably the most accomplished of the four with a recent major exhibition at The Courtauld of paintings of over-sized black figures. It’s the simplest conceptually as it wants to bring black figures to the fore given they’ve been under-represented in Western art history, as she asserts ‘‘Black people have existed in the past, exist now, and will exist in the future, that we belong to all times”.

It’s by no means a five-star exhibition and Claudette Johnson and Pio Abad’s works have a clearer message to them, but it’s the first year in a while where it feels like every artist deserves to be here on their merits.

Previous years have felt like they were trying to reclaim relevance and ended up feeling gimmicky with all film artists (2018), having all four artists win (2019), shortlisting only collectives (2021) or worse having some artists present that felt like they were there to make up the numbers.

However, this year I think any of the four could be worthy winners and the idea of identity isn’t just relevant in contemporary art but to the UK’s wider sociopolitical climate where politicians have been stoking fires with anti-migrant rhetoric and where riots across the country have been fuelled by racist fervour.

This is a difficult time for the UK as it has to decide what kind of country it will become as it confronts the dark past of the British Empire and I hope it becomes the multi-cultural society I think it can be. It’s an important conversation happening across the country and these four artists are part of it.

The Turner Prize format itself is still imperfect and improvements could be made by making it free to enter every year - it’s ticketed at Tate Britain but was free when it was at Towner Art Gallery in Eastbourne last year. I’ve also long advocated that visitors should pick the winner - given the jury picked the shortlist - each visitor should be given one vote. This approach could foster greater local engagement, as it would have been meaningful for residents of Hull, Derry, or Margate to pick the winner when the Prize was hosted in those cities. This would also help repair the image of contemporary art as elitist and dominated by London’s influence.

Though the Turner Prize may never recapture the past celebrity-fueled buzz - Madonna is unlikely to be awarding future prizes, as she did in 2001 - it seems to be moving in the right direction. With this year’s cohort of artists, the Prize is addressing timely, thought-provoking themes, and one can only hope it continues to embrace this level of quality and relevance.

Turner Prize 2024 is on show at Tate Britain until 16 February 2025, with the winner announced on 3 December 2024.

Cover image: Installation view, Claudette Johnson’s presentation in Turner Prize 2024 at Tate Britain 25 September 2024 – 16 February 2025 ©Tate

Tabish Khan is an art critic specialising in London's art scene and he believes passionately in making art accessible to everyone. He visits and writes about hundreds of exhibitions a year covering everything from the major blockbusters to the emerging art scene.

He writes for multiple publications, and has appeared many times on television, radio and podcasts to discuss art news and exhibitions.

Tabish is a trustee of ArtCan, a non-profit arts organisation that supports artists through profile raising activities and exhibitions. He is also a trustee of the prestigious City & Guilds London Art School and Discerning Eye, which hosts an annual exhibition featuring hundreds of works. He is a critical friend of UP projects who bring world class artists out of the gallery and into public spaces.