How I learned to stop worrying and embrace immersive art experiences?

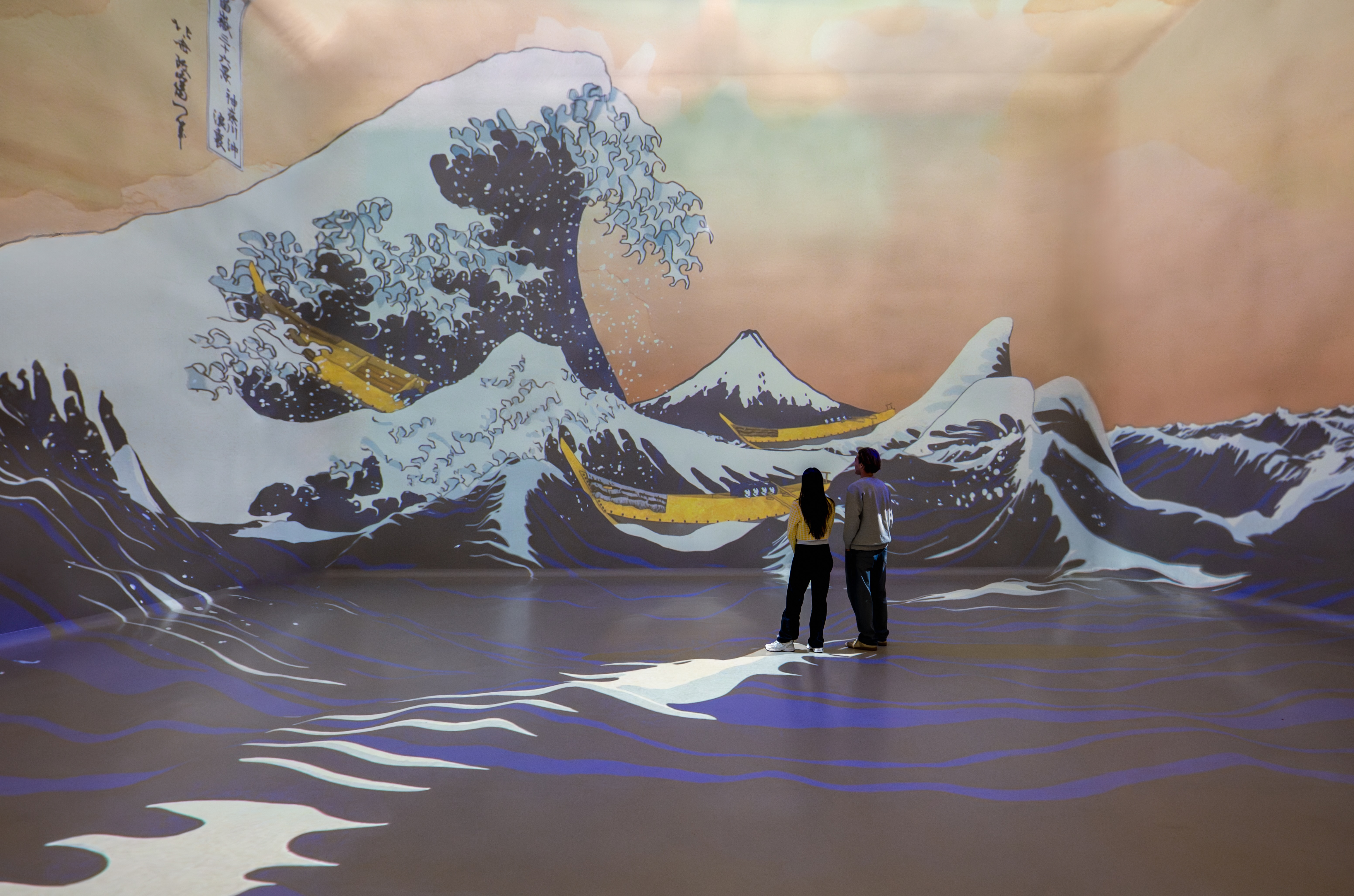

I’m sitting down and staring at Hokusai’s famous artwork the Great Wave off Kanagawa, where a large wave subsumes a boat with Mount Fuji in the background. However, instead of looking closely at a framed woodblock print the Great Wave is all around me and it’s building and rolling across the walls - accompanied by dramatic music.

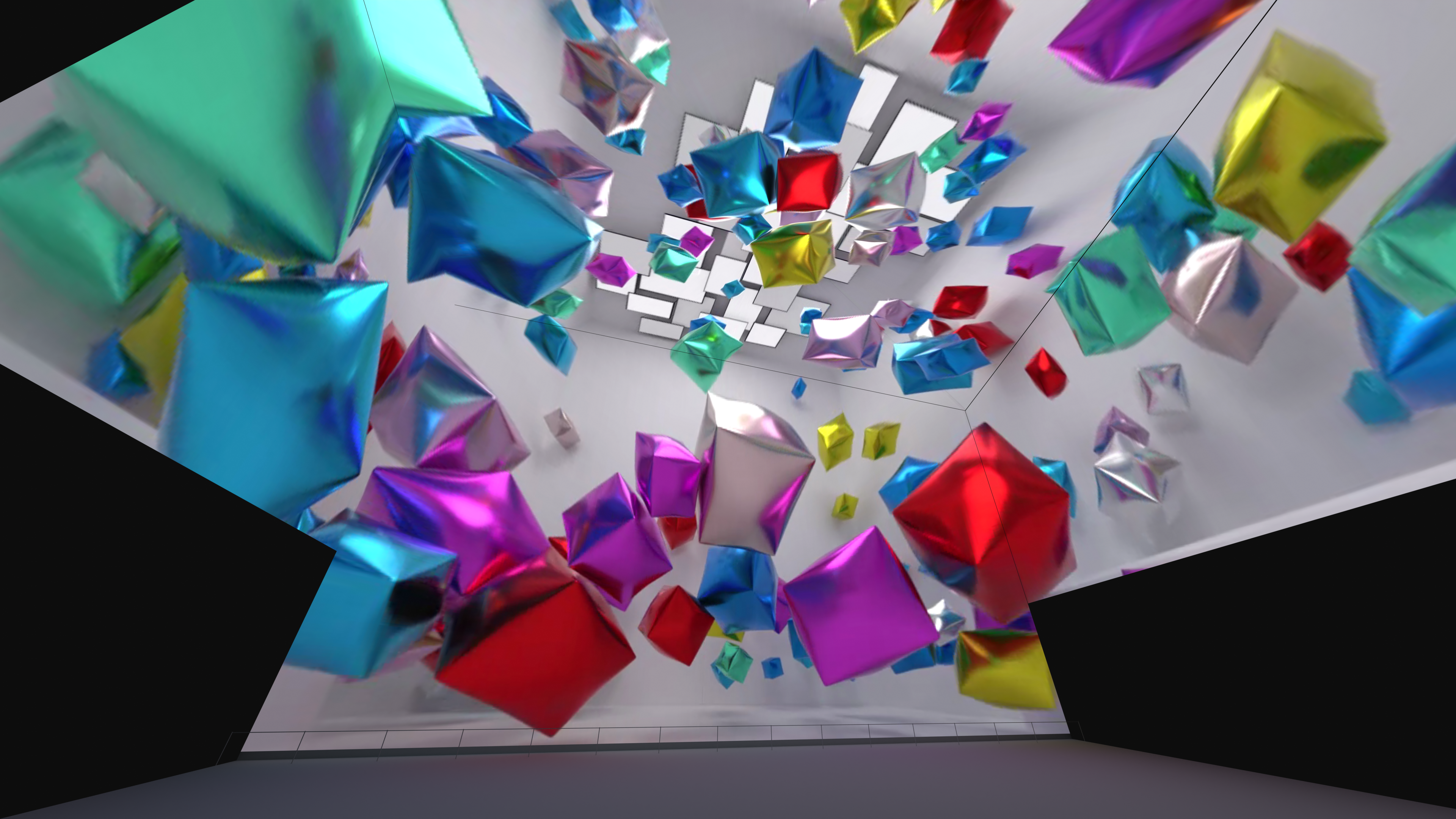

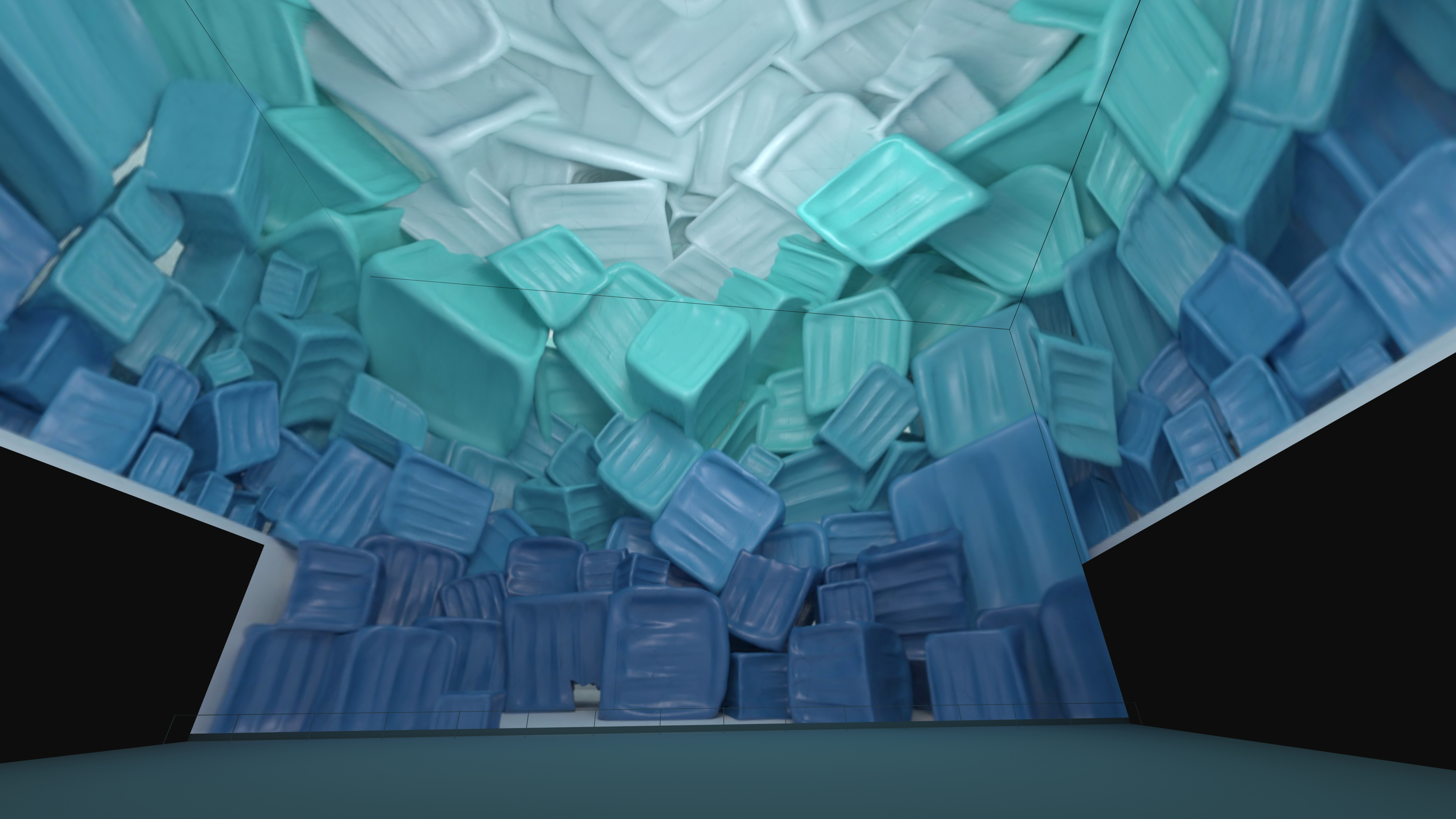

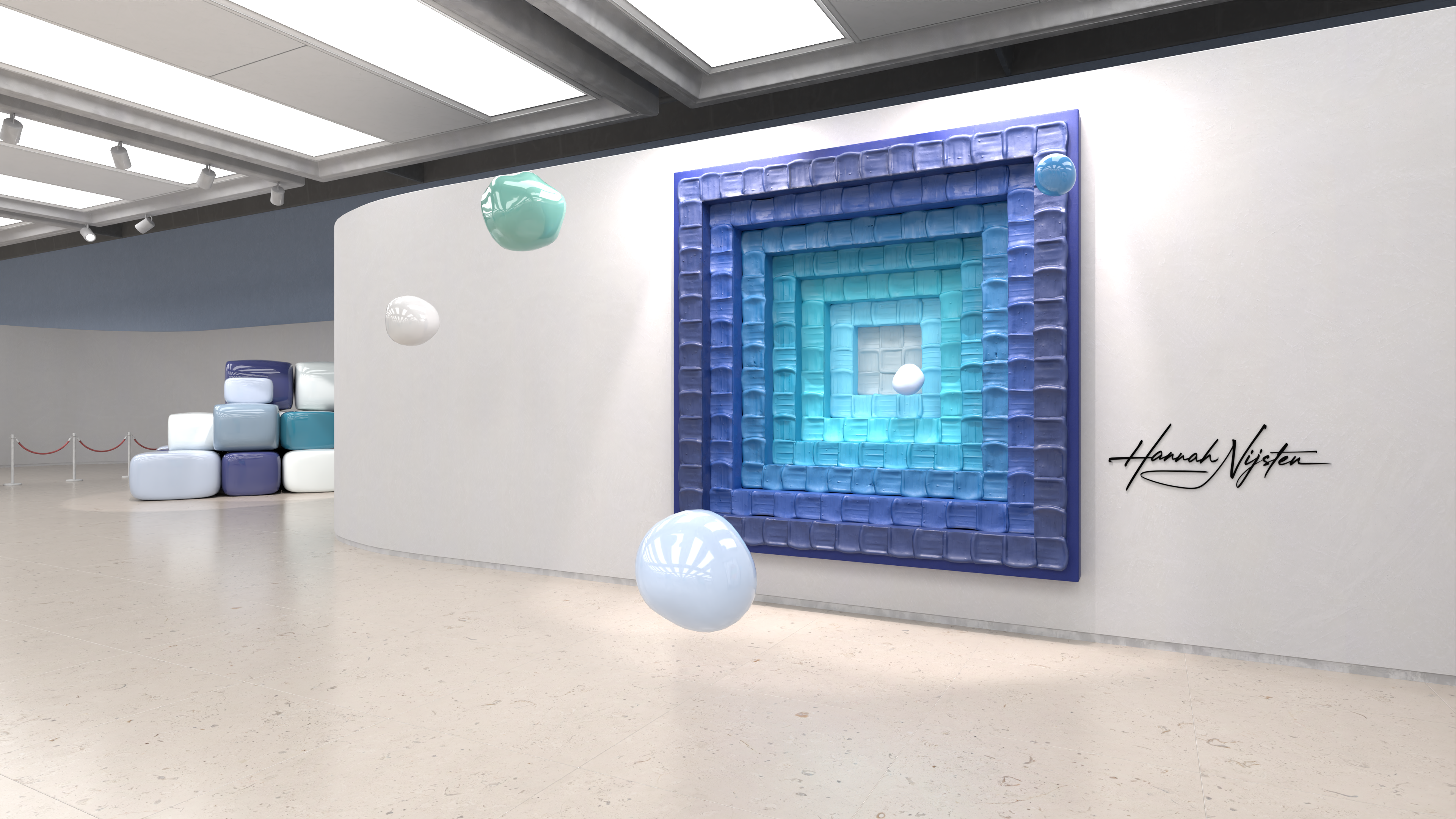

I’m inside Frameless, an immersive art experience in London that uses digital projectors to take classic artworks and animate them so that we can sit or stand in a room and be surrounded by an immersive environment based on paintings by Vincent Van Gogh, Rembrandt, Hilma Af Klint and many more.

It’s not the only immersive art experience in town and new ones pop up regularly, the latest one to open is Moco London and it’s only a few doors down from Frameless, though Moco already has branches in Amsterdam and Barcelona.

Here in London we also have Lightroom, which has a David Hockney immersive experience, that’s returned for a second run due to its popularity and the always-on and outdoor Outernet screens next to Tottenham Court Road. On the more science-like side of immersion, we also have Twist Museum and Paradox Museum - the latter has 16 incarnations worldwide from Las Vegas to Shanghai.

It’s a global phenomenon that also includes Atelier des Lumieres outside Paris and the global franchise ‘Museum of Ice Cream’, which I’m surprised hasn’t yet established a foothold in London and wouldn’t be surprised if it did in the next couple of years.

We haven’t even touched on the temporary immersive experiences but one thing is for certain, as soon as one opens critics like me are lining up to pour scorn on them. Florence Hallett writing for ‘the i’ said a Van Gogh experience was “voyeuristic, distasteful and spectacularly uninformative” and Eddy Frankel writing for Time Out, reviewing the recently opened Moco Museum, referred to immersive art in general as “London is just entering its lobotomy era”. I’ve also savagely critiqued similar exhibitions and said of a Bob Marley exhibition at Saatchi Gallery “you may enjoy parts of it, but you’ll feel emptier after and hate yourself for it”.

The above are valid critiques and I have witnessed many a terrible immersive art experience. However, when I look at the families, couples and solo visitors in most of these immersive exhibitions they look happy - snapping away content for social media and not grumbling about the fact they’ve shelled out £20 or more per ticket. It made me ask myself, what if I’m wrong?

Not that it’s wrong for art critics to be critiquing an immersive experience when they feel it’s sub-par, but that art critics are part of a system that writes for people who are already discerning when it comes to art. These immersive experiences often appeal to those who find traditional galleries and museums hard to access or as places that are ‘not for them’.

As Frameless Art Curator, Rosie O’Connor states: “We know that people who visit galleries as children are more likely to consume culture as they reach adulthood, but they can struggle with the height of the paintings and inaccessible language rooted in the art world. At Frameless the whole experience has been designed to be entertaining and accessible to all with an aim to spark an interest in these magnificent artworks and to hopefully even inspire visitors to seek out the original versions”. That’s a great goal that anyone who thinks art should be everyone can get behind.

We should talk about price as many of these immersive experiences are expensive, largely due to the technology used, London rental costs and other overheads. Both Frameless and Moco London start around the £20 mark for adults, but that’s similar to most major museums where exhibition tickets are now regularly north of £20. Though it’s important to note that some like Outernet London are publicly accessible to anyone and are there’s no charge.

Making art accessible is a key goal of mine and many other art professionals, and we should be open to celebrating any novel attempts to make art accessible even if it doesn’t fit into the traditional museums and galleries model that we’re used to.

Statistics from 2018-19 from the UK’s Department of Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS)1 showed that just over 50% of adults had visited a gallery or museum at least once in the last year and this number is lower among Asian (43.7%) and Black (33.5%) people. The difference is even starker when you look at professional occupations (66%) and more manual occupations (36%)2. It shows that there is a large untapped group of people not engaging with visual art and if these people who don’t frequent galleries and museums prefer an immersive art experience, then I’m all for it.

Established London institutions like Tate Modern and The National Gallery will put on press views where critics and other journalists can see an exhibition before it opens to the public to get write-ups about their exhibitions, while it’s telling that immersive experiences focus more of their time and budget on influencers and social media marketing.

Some of the approaches used by immersive experiences have been adopted by the more traditional institutions and Tate Modern often has influencer views running concurrently with press views when the exhibition is particularly visually appealing - ‘Instagrammable’ is the new phrase that’s often used to describe such art.

Art is not alone in this move towards experiences and this wider trend of people shifting their spending away from goods to experiences has affected the wider arts, shopping centres, restaurants and many other sectors as they all move towards providing memorable experiences to all visitors. It’s a phenomenon that’s often referred to as the experience economy.

If we stick with Tate Modern as an example it has hosted a Yayoi Kusama Infinity Rooms that was extended several times, due to popular demand, so it ran for three years instead of the originally planned twelve-month run. It has also brought in interactive artworks over the Summer holidays so families can get hands-on with creativity - with Oscar Murillo’s installation occupying the Turbine Hall space in Summer 2024.

Val Ravaglia - Curator, Displays & International Art at Tate Modern adds that “At Tate Modern, it has been our continued ambition to programme exhibitions and displays that engage a younger and more diverse audience, which has been effectively realised with exhibitions focusing on immersive and interactive art experiences over the last few years, especially the Turbine Hall commissions, recent exhibitions of work by Olafur Eliasson and Yayoi Kusama, and our UNIQLO Tate Play programme. This kind of art practice is not by any means a new phenomenon, but a continuation and development of ideas that artists have employed for years to make the presence and movements of the audience an integral part of their works”.

We’ll likely see the lines blur further between traditional art space and immersive experiences as they both tap into the demand from visitors for unique experiences and while cynics may see this as a dumbing down of arts and culture it doesn’t have to be seen in that way and this approach is a reflection that the arts have been and largely remain elitist.

We’ve seen this at Outernet which has worked with established art institutions. Alexandra Payne, Creative and Content Studio Director for Outernet London says: “... we've been committed since opening our doors almost 2 years ago to championing the importance of public art within the urban landscape. We are now the UK's number 1 visited cultural attraction due in large part to us providing free accessible art and experiences … This unique position has resulted in meaningful partnerships with some of London's most established art institutions such as The Tate, Saatchi Gallery and The Serpentine as they recognise our ability to reach a diverse audience and the value our platform brings to the art world”.

There’s space for film buffs to gain value from action movies and avant-garde cinema, music fans to enjoy both pop and classical and for readers to consume both page-turners and more challenging reads. Likewise, there should be space for the visual arts to contain a spectrum of art and art experiences. The easier access points to an art form may act as a gateway to the more challenging elements - i.e. people who read page-turner thrillers may then try out a classic novel.

Based on excellent visitor numbers to blockbuster exhibitions at major museums there’s no suggestion that art experiences are stealing audiences from the more traditional art institutions. They may even be opening up art to demographics who have never felt comfortable engaging with art in a traditional setting and that can only be a good thing.

Tabish Khan is an art critic specialising in London's art scene and he believes passionately in making art accessible to everyone. He visits and writes about hundreds of exhibitions a year covering everything from the major blockbusters to the emerging art scene.

He writes for multiple publications, and has appeared many times on television, radio and podcasts to discuss art news and exhibitions.

Tabish is a trustee of ArtCan, a non-profit arts organisation that supports artists through profile raising activities and exhibitions. He is also a trustee of the prestigious City & Guilds London Art School and Discerning Eye, which hosts an annual exhibition featuring hundreds of works. He is a critical friend of UP projects who bring world class artists out of the gallery and into public spaces.