The Folk Renaissance: Tradition, Nature, and Cultural Resistance

From seasonal rituals to traditional crafts, more and more young people are turning to folk heritage as a way to reconnect with themselves and the world in an age of disconnection.

“All of my friends seem very interested in the moon at the moment”, I told my cousin as we sat down to dinner. I had just finished Ben Edge’s Folklore Rising, a book about the author’s travels around the UK visiting and then painting folk festivals and traditions, and had started tracking my period with Stardust, an app that tells you what house the moon is currently in as well as your menstrual phase, so I was also feeling more lunar-curious than before. We discussed the shift we were seeing in the young women around us: whether it was coming from a place of spiritual inquisitiveness, or seeking to balance our hormones, or to find a work-life balance that didn’t make us feel like a cog in a machine, we were all looking for something more than - or certainly different from - what capitalism was selling us as a “good life”.

Over on Instagram, I was discovering more artists, accounts, and brands immersing themselves in folklore and traditional crafts. From @thechurchkneelerarchive sharing images of church kneelers woven with everything from Bible quotes to Mickey Mouse, to perfumery Ffern launching their ‘Ffern Folk Foundation’ awarding grants of £50,000 to British folk art practitioners, tradition was “in”. My algorithm may well have been adjusting to my own interest in all-things-folk, but heritage crafts and nature-focussed mythology appeared to be having a comeback. Once a niche field of interest, shelves of bookshops were now filling up with titles about folk craft and pagan calendars, including historical reinterpretations like Queer as Folklore by Sacha Coward and volumes of folk-inspired illustrations like Folkish by Victionary, and online creators were making folk tales their focus, sharing to hundreds of thousands of followers in the case of Movern Graham.

Dr Guy Hayward, who also shares his folk practices online, is the co-founder and director of the British Pilgrimage Trust, which works to make pilgrimage - which Hayward defines as “a journey on foot to holy/healthy/holistic/welcoming places, bringing your own beliefs” - more accessible. During these pilgrimages, Hayward sings, “drawing on the folk and sacred music of the British Isles to animate the landscape with story and memory”.

He seems to agree with my theory that we are seeking out traditions that connect us with nature as a remedy to the fast-paced and corporately appraisable way we have found ourselves living our lives. “There’s a growing awareness that something vital has been lost in our relationship with the natural world and with our own inner lives”, Hayward tells me, “as global systems shake and digitised life accelerates, people are turning to what feels grounded and enduring. Folk traditions offer us continuity, ancestral connection, and the acknowledging of seasonal rhythms. They’re embodied and local — an antidote to abstraction and alienation.”

“Folk histories and traditions offer a counterweight to modern disconnection,” he says, quoting the growing numbers of people attending pilgrimages and other traditional celebrations and events as evidence for this folk resurgence, “there’s a quiet hunger for belonging — not just to place, but to time.”

Lally MacBeth, an artist, curator, and author of ‘The Lost Folk’ (and the founder of @thefolkarchive which runs the account for the church kneelers), spoke to me about the revival she has been witnessing, which “feels very young, inclusive and open which is really exciting, and I think is incredibly hopeful for the future of folk.” MacBeth pinpoints living by the calendric year - marking the changing seasons with celebrations and rituals deeply rooted in nature - as a selling point for new enthusiasts: “the fact that each year on May 1st you can dance around a maypole, that at Summer Solstice you can wake at dawn to watch the sun rise and that in December you can Wassail an apple tree - all offer a sense that despite everything the world keeps turning. In a world of instability this can feel very grounding.”

These traditions, MacBeth believes, offer us hope in “tumultuous times”, offering us “the sense that we can make a difference in the world - sometimes 'folk' can be projected as something silly or odd but I think it has the potential to be really radical in the way it moves conversations forwards, particularly around climate and ecology. Through celebrating seasonal customs we can bring greater awareness to the changing planet and it can help us think of positive solutions to how we tackle things like food insecurity, global warming and increased environmental disasters.”

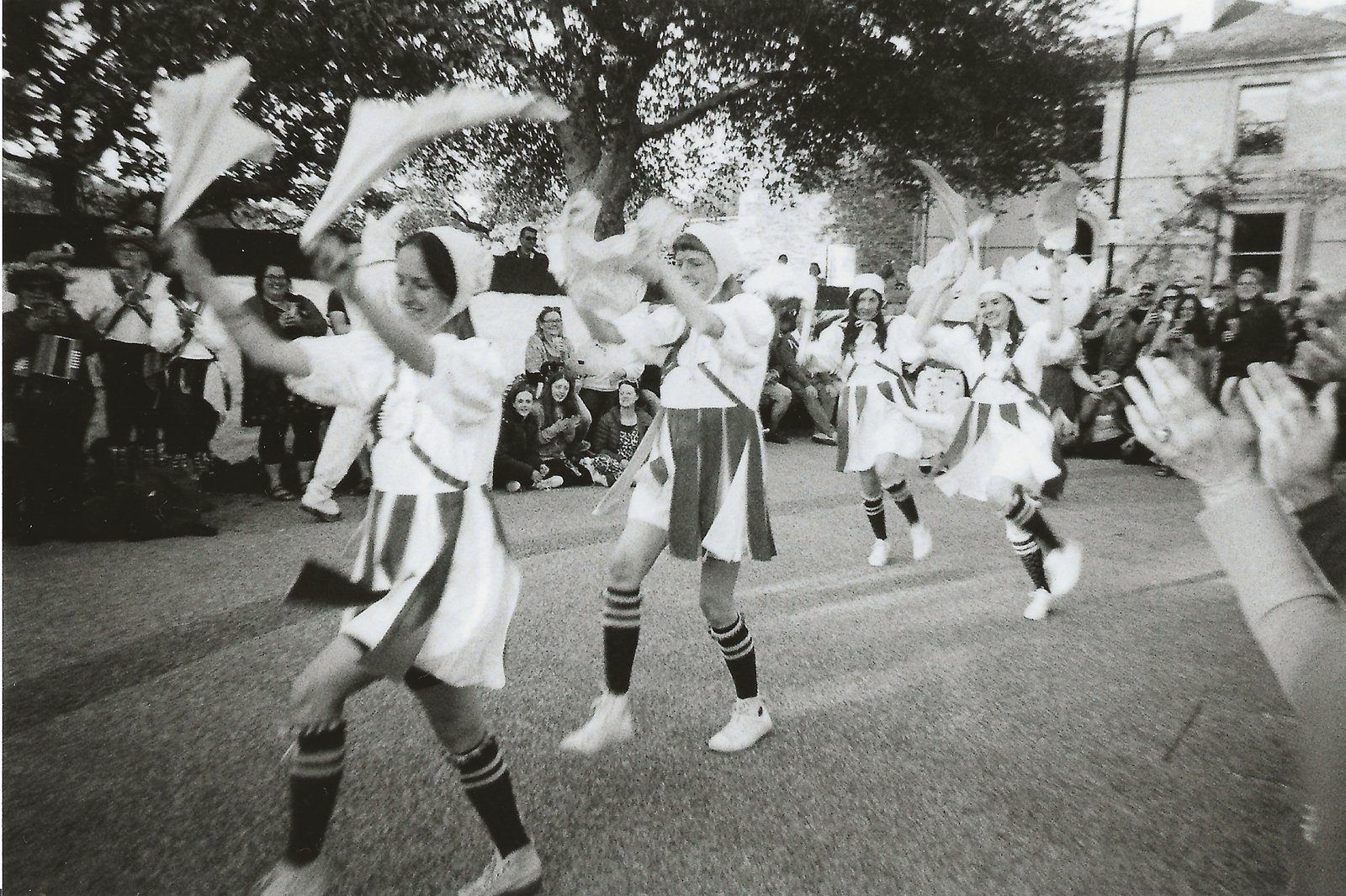

Lally MacBeth - The Mock Morris performs Fishsticks & Fiddlesticks at Lanyon Quoit, 2020

Lally MacBeth - The Mock Morris performs Fishsticks & Fiddlesticks at Lanyon Quoit, 2020

This same radicalism is at the heart of Common Folk Collective’s mission on the Wirral peninsula. The collective explores local folk culture, alternative histories, and supports community arts through performances, exhibitions, and workshops, aiming to “recover, reimagine, reclaim, and re-politicise folk for both old and new audiences.” Co-founder Rachel Collett spoke to me about the political foundations of the folk revival happening in the UK: “Capitalism has alienated us from one another and from our customs, histories, and environment. People are desperate for connection. Unfortunately some people are finding that in toxic ways, like far-right politics. So in many ways, the folk revival is an important counter to the rise of dangerous right-wing nationalism. We are part of a movement that is pushing back against the co-opting of Englishness, trying to reclaim and recover a national identity that isn’t exclusionary or reactionary.”

While ten years ago folklore and traditional crafts may have seemed an endangered interest on the verge of extinction - held up by a handful of kooky barefoot pensioners - the pandemic seems to have changed things. A glimpse into a world not dictated by productivity, and feelings of insecurity generated by global turbulence, have left people yearning for alternative ways to connect, worship, and structure our lives. A return to folk ritual isn’t a regression, however, as young people prove that they are innovating on tradition (often out of necessity as many rituals have been lost to history) to create their own empowering practices. This isn’t simply a return to folk tradition, but truly a renaissance, morphing to fulfil our fundamental, ancient needs in a modern world.

Cover Image: Lally MacBeth - The WAD dancing at a Morris gathering, Helston, Cornwall, May 2024

Verity Babbs is an art historian, presenter, and comedian from the UK. She hosts live art-themed comedy nights 'Art Laughs' which perform regularly at London's National Gallery, and she has appeared on BBC Radio 4 and BBC News. She has written for several arts publications including the Guardian, RA Magazine, Hyperallergic, and Artnet News, and has worked as a presenter for Tate, London Art Fair, and Elizabeth Xi Bauer gallery.