The denied face

Denial and absence in contemporary portraits. Just a new trend of artists or a real social rebellion?

There is a work by Adrian Ghenie, “Pie Fight Study,” in which a well-dressed man is destroying his own face: the figure's hands sink into the oil paint-literally-to drag the color mixture into a lump of matter. There is no anger in his gesture, no pain. Only tension gathered in a self-manipulation that returns an icy coldness, certainly disturbing. Looking at it, the impression is that the artist is inviting us to confront a humanity dissolving before our eyes. It seems that the man, by extension, embodies a dark human desire that is opposed to the primal instinct of preservation, as if to erase any possible “portrait,” understood as an aesthetic act.

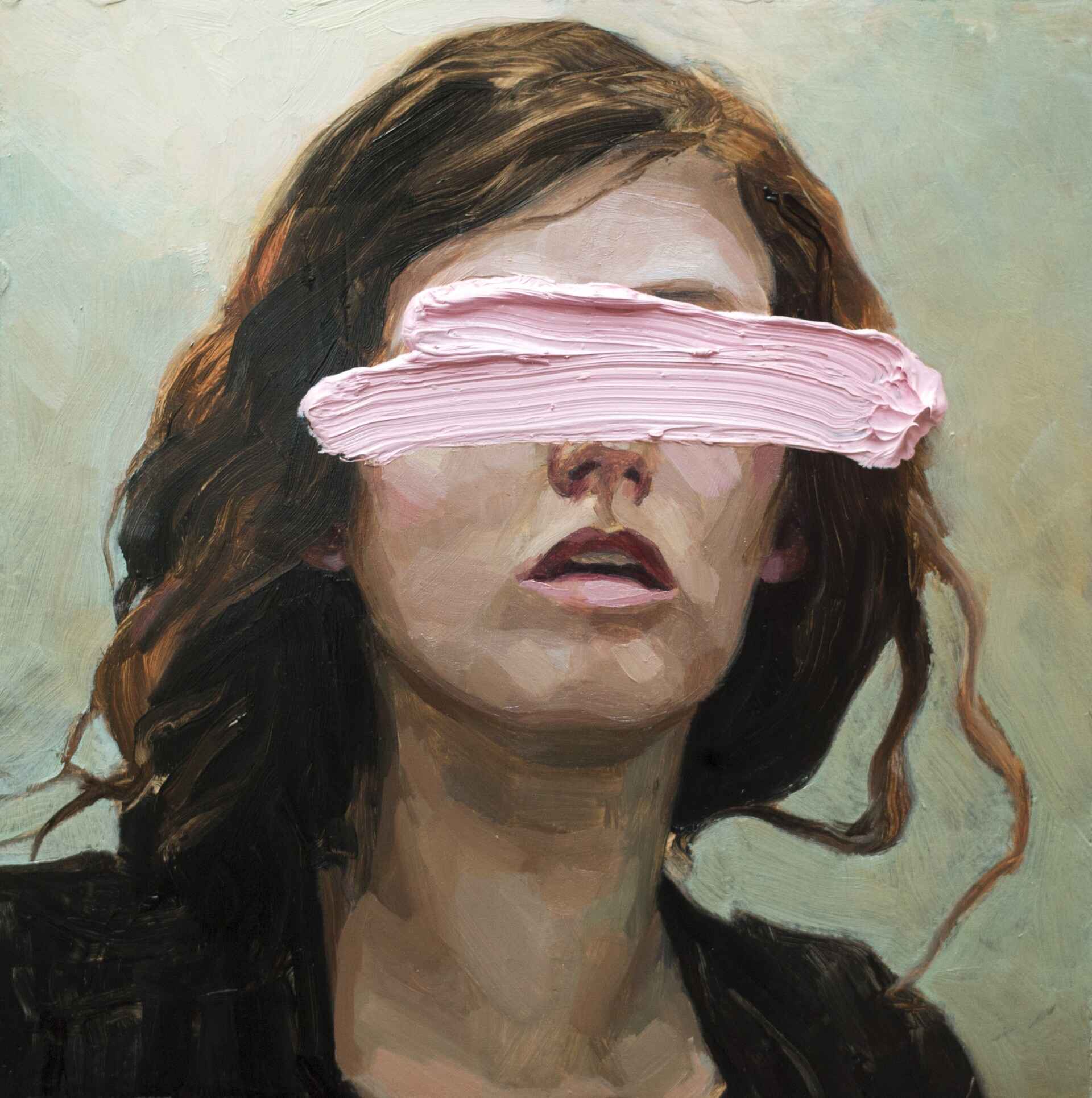

The work of Ghenie, a very talented Romanian artist, is just one of the many examples of a trend that, recently, has been gradually emerging in figurative painting: “faces,” amidst erasures, censorship, distortions and metamorphoses, are gradually disappearing from contemporary canvases. It must be said that there are, as is natural, numerous perspectives to analyze this curious “trend”: the most mischievous, to begin with, might dismiss the matter by asserting that artists are simply incapable of painting human faces with dignity. It seems to me, in all honesty, a legitimate but captious assumption, especially in the pictorial quality expressed in the works of artists who deliberately choose to “censor” faces within their works. I find it hard to believe that a very skilled painter like Henrietta Harris, just to take one example, would choose to obscure the faces featured in her “Fixed It” series to compensate for technical gaps.

Henrik Uldalen, Rift , 2016-2021, Oil on wood, 30 x 30 cm, Courtesy of JD Malat Gallery

Henrik Uldalen, Rift , 2016-2021, Oil on wood, 30 x 30 cm, Courtesy of JD Malat Gallery

I consider it more plausible, if anything, that contemporary artists are rebelling against the historical centrality of the portrait in order to explore new stylistic and conceptual possibilities. For centuries, perhaps millennia, the face has been the symbol of individuality excellence. Not only: the portrait, when commissioned by monarchs, religious authorities and aristocrats, acted as a veritable status symbol of the economic power and authority of those who could afford the work of an artist. And even moving away from the logic of the ‘court painter’, portraits have almost always served to capture the essence of the subject, rendering a vision that celebrates the person and the personality. This narrative today seems to have definitively entered a crisis. Artists who choose to remove faces in their work do not just destroy a symbol: they transform it into a void, into an invitation, perhaps to rethink what it means to be human, yearning for a universality of art that clashes with the individualistic fragmentation of a hyper-subjectivised society.

Henrik Uldalen, Trance, 2018, Oil on Wood, 120 x 180 cm, Courtesy of JD Malat Gallery

Henrik Uldalen, Trance, 2018, Oil on Wood, 120 x 180 cm, Courtesy of JD Malat Gallery

Now, I seem to be restating the obvious: but do we really live in an era where the human face dominates any form of visual communication? From selfies to hyper-realistic AI-generated avatars, from 9:16 videos (the perfect format for a close-up) to profile pictures, the face has become the symbol par excellence of our technological ‘individuation’ understood, precisely, as the triumph of the individual. It is the focal point through which we construct identities, convey emotions and create connections and parasocial relationships. Faced with this overexposure, artists seem to respond with an act of visual revolution.

Henrik Uldalen, above all, has become very famous (especially online, and this is something we will return to in a moment) for his hyperrealist portraits in which faces, painted with absolute mastery, are dissolved in abstract brushstrokes, almost as if to ‘prove’ a crucial term that what we see is ‘only’ the surface of a canvas. His painting is not a traditional portrait, but a dialogue between technical perfection and the negation of identity. Likewise, his gesture is also conceptual (and very ‘practical’): in a world where the face dominates communication, erasing it means shifting attention to something else - the quality of the medium, the act of painting itself. Showing a perfectly painted face is no longer enough to capture the attention of digital users: artists must immediately return the technical value of their work, and they do so by openly showing the process, the materiality, the imperfection ( although intentional and artificial, when all is said and done).

Henrik Uldalen, Untitled, Oil on Wood, 180 x 120cm, 2019, Courtesy of JD Malat Gallery

Henrik Uldalen, Untitled, Oil on Wood, 180 x 120cm, 2019, Courtesy of JD Malat Gallery

When Uldalen dissolves the faces of his figures, he invites us to look beyond the subject, guiding our gaze towards the painting itself: the way the colour spreads across the canvas, the movement of the invisible hand that creates - and sometimes destroys. This focus on the medium is a way of standing out in a visual landscape dominated by the digital image, a return to materiality in an age of virtuality. As art critic Rosalind Krauss rightly observes, contemporary figurative art increasingly tends to focus on the ‘specificity of the medium’: on painting's unique ability to communicate through materiality and texture. In digital hyperreality, where everything is immaterial and reproducible, artists reaffirm the physical presence of the work, and do so by making the painterly gesture visible.

Henrik Uldalen, Exhale, Oil on Wood, 150 x 300 cm, 2018, Courtesy of JD Malat Gallery

Henrik Uldalen, Exhale, Oil on Wood, 150 x 300 cm, 2018, Courtesy of JD Malat Gallery

But if the face disappears, can one still speak of a ‘portrait’? The figurative distortion of the face, even its partial dissolution in pictorial matter, is only one of the many expressive possibilities emerging in the contemporary figurative trend. As mentioned, hiding the face is not simply a denial, but also - sometimes, at least - a conscious strategy to amplify the universal meaning of a work. In any traditional portrait, the face always tells a specific, implicit, story: the painting defines and crystallises a unique identity of a recognisable individual. It is, in the viewer's mind, an ‘other than oneself’. Eliminating the face, with all the technical possibilities attached to this censorial practice, necessarily dissolves the individual dimension, transforming the subject into a symbol, into a kind of open container in which the spectator can project himself.

Hélène Delmaire, Glitch II, oil on wood, 2018

Hélène Delmaire, Glitch II, oil on wood, 2018

From a psychological point of view, this phenomenon can be explained through the theory of symbolic identification. Already Carl Jung, speaking of universal archetypes - collective images that inhabit the human unconscious - explained that the symbolic power of a visual text manifests itself most intensely when it is linked to a specific individual. A ‘denied’ face, in this sense, becomes an idea, a representation of the human condition shared on a narrative and phenomenological level. The absence of distinctive features allows the viewer to enter the work without the barriers that a specific identity might erect, creating a deeper empathic bond.

Bobbi Esser, The World at Our Command, 245 x 300 cm, Oil paint on canvas,2024, Courtesy of Unit Gallery

Bobbi Esser, The World at Our Command, 245 x 300 cm, Oil paint on canvas,2024, Courtesy of Unit Gallery

Neuroscience supports this intuition. Studies on the activation of brain areas during the observation of works of art, such as those conducted by Oshin Vartanian (which we have already discussed in other articles in the magazine), show that vagueness or ambiguity in a visual representation stimulates greater activity in centres related to imagination and personal projection. In other words, what is not faithfully connoted to formal reality - such as a hidden or erased face - invites the viewer to complete the image with their own thoughts, emotions and memories. The work, following this principle, turns into a psychological mirror - an ‘aesthetic’ place in which everyone can recognise a part of themselves. Paradoxically, therefore, a work that refuses to represent a specific face manages to speak directly to collective humanity. Eliminating individuality, put in these terms, is not a loss, but a conquest: the subject becomes the symbol of a universal experience, capable of evoking emotions and meanings that transcend the boundaries of the painted person. It is a form of democratisation of art, which no longer belongs to the subject portrayed, but to anyone who observes it.

Hélène Delmaire, Still Life With Flowers IV, oil on wood, 2015

Hélène Delmaire, Still Life With Flowers IV, oil on wood, 2015

Finally, censoring the face is also a way of questioning the power dynamics behind its representation. Social media, to return to the hyper-connected contemporary landscape, are never really neutral: they reward certain types of faces, certain standards of beauty, certain ways of showing off. To deny the face is to deny these dynamics, to refuse to participate in a system that reduces the individual to a consumable image.

In this sense, artists are not just reacting to a dominant aesthetic: they are constructing a ‘political’ and cultural critique. In a world where the face is commodified, erasing it means affirming the value of the invisible, the inaccessible, the unspoken: considering the visual infodemy of the digitised world, this is quite a revolution.

Cover image: Hélène Delmaire, Marie (eyeless girls series), oil on wood, 2017

Creative, teacher and expert in visual culture, Alessandro Carnevale has worked on TV for several years and has exhibited his works all over the world. In 2020, the Business School of Il Sole 24 Ore included him among the five best Italian content creators in the artistic field: on social media he deals with cultural dissemination, covering a wide spectrum of disciplines, including the psychology of perception, semiotics visual, aesthetic philosophy and contemporary art. He has collaborated with various newspapers, published essays and written a series of graphic novels together with the theoretical physicist Davide De Biasio; he is the artistic director of an open-air museum. Today, as a consultant, he works in the world of communication, training and education.