The art of immediacy. Processing Fluency Theory, cognitive challenges and aesthetic pleasure

In 1927, in the heart of a Berlin in cultural turmoil, noted German psychologist Max Wertheimer received a strange letter that would forever change the course of his career. The letter came from an old friend of his, Otto Baumer, an art enthusiast and collector who, fascinated by the new art movements of the time, was trying to understand why certain works immediately caught the public's attention.

Max Werheimer (1880-1943)

Max Werheimer (1880-1943)

Otto Baumer had just visited an exhibition of abstract art and noticed a curious phenomenon: people stopped longer in front of a small group of works, devoting only a few seconds of their time to the others. Intrigued, he wrote to Wertheimer to ask if there was a psychological explanation to account for the visitors' peculiar reaction.

Radtachistoskop

Radtachistoskop

Wertheimer, at the time already established in the scientific community for his work on Gestalt psychology, had always been fascinated by the way we perceive shapes and images, and Baumer's letter ignited a spark of curiosity in him. Not only did he reply to his friend, but he decided to explore the question further, convinced that behind that question lay a psychological truth about human nature.

“Dear Otto,” he wrote, ”your remark struck me deeply. I wonder if immediate perception is not an intrinsic aspect of our psyche. Perhaps what seems immediately comprehensible to the eyes is what our minds recognize as a universal pattern.”

Baumer's letter was a kind of catalyst for Wertheimer. Over the next few months, the psychologist began to frequent museums and art galleries assiduously, observing the behavior of visitors with great care. During one of these visits, he came across a work by Kandinsky: he noticed that, despite its apparent complexity, the painting seemed to elicit an immediate response from visitors. He wondered if it was the use of colors or the arrangement of shapes that made the work so “pleasing” and immediately appreciated by the audience.

Vassily Kandinsky, 1923, Composition 8, Oil on canvas, 140cm x 201cm, Musée Guggenheim,New York

Vassily Kandinsky, 1923, Composition 8, Oil on canvas, 140cm x 201cm, Musée Guggenheim,New York

“It's like a melody we already know,” Wertheimer thought, an insight that prompted him to consider how our minds can be predisposed to find beauty in what resonates and reverberates as a familiar element. Seventy years later, after a long tradition of studies on aesthetic perception and cognitive psychology, his ideas would find a solid foothold in the research conducted by Rolf Reber, Norbert Schwarz, and Piotr Winkielman, who in 2004 formalized Processing Fluency Theory, a theoretical model that I applied extensively in writing the incipit of this article.

Here, to understand it, the whole story about Wertheimer, the letter from Baumer, the insight in front of the Kandinsky painting: nothing like that ever happened. The tale, however “plausible,” is a figment of my imagination. Mind you, it is true that Gestalt psychology (of which Wertheimer is one of the founding fathers, along with Wolfgang Köhler and Kurt Koffka) has extensively studied the perceptual relationship that is established between work and viewer, but to claim that there is a direct connection between Gestalt psychologists and Processing Fluency Theory is a conceptual stretch. Why all this “theatrics,” then? To show that Reber, Schwartz and Winkielman's theory, formulated in the early 2000s, is very current and concrete, and its applications in the aesthetic sphere (which we will talk about in a moment) are indeed manifold.

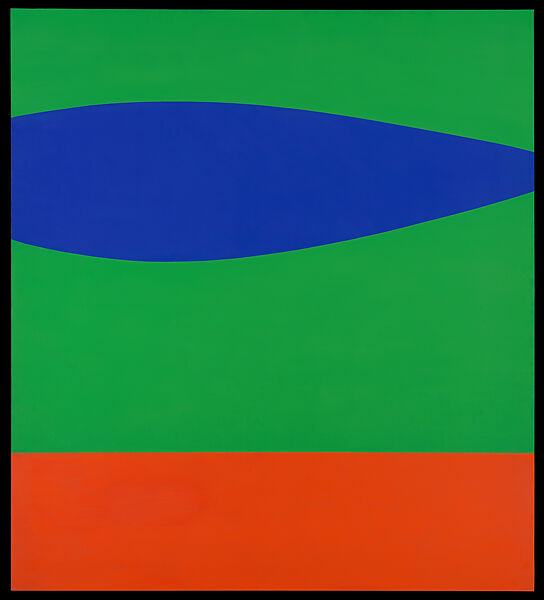

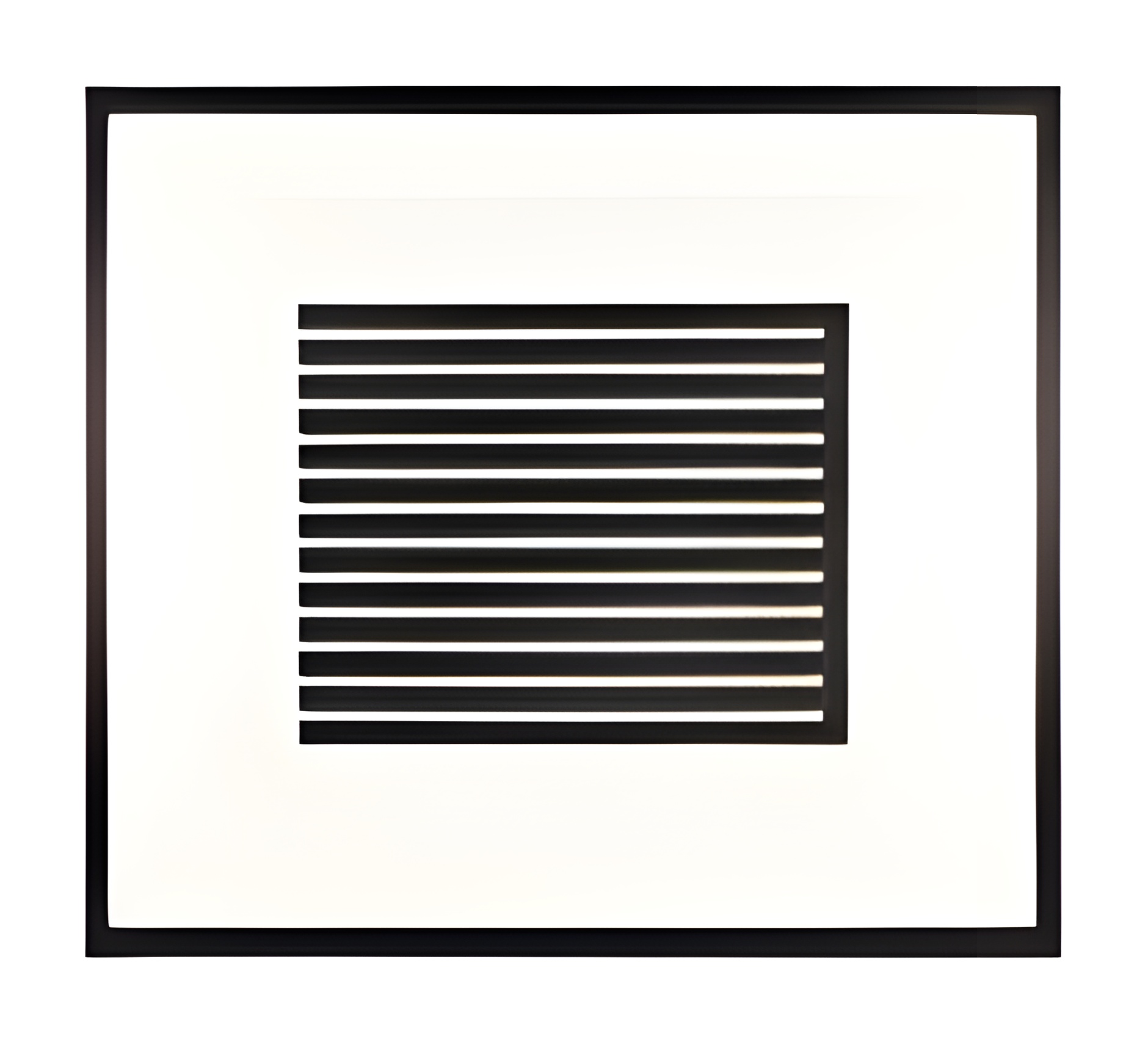

Donald Judd, Untitled, 1991

Donald Judd, Untitled, 1991

Now, “processing fluidity theory” is a psychological model that explains why we find some experiences more pleasant than others, based on the ease with which information is processed by our brains. The theory suggests that stimuli that are easily processed turn out to be more pleasurable than complex, heterogeneous, ambiguous stimuli. Aesthetic pleasure, consequently, is defined according to the cognitive dynamics of the perceiver and not as an objective quality of the stimulus. The term processing fluency refers to the metacognitive experience of ease or difficulty with which new data are processed, referring to the (almost always unconscious) perception of one's own cognitive flow: in preference judgments a high degree of fluency corresponds to a high degree of preference. This is because the experience of “fluency” is accompanied by feelings that tend to be positive.

Let's go back to the incipit of the article: the anecdote about Max Wertheimer and the letter is a storytelling technique based on a narrative pattern as simple as it is widespread, to which-and here we come to processing fluency-we are largely accustomed. Personal anecdotes, to wit, immediately create an emotional connection with the reader; even if fictitious, the story evokes an era rich in intellectual ferment, into which a “narrative engine” (the letter) is inserted that traces a pattern in which a single detail breaks the balance of the text, and instills a doubt that we feel the need to want to clarify. Starting a story with a mystery element stimulates the reader's curiosity, who loses sight of the scientific “subtext” of the article: in the first few paragraphs, your goal was not to delve into a complex psychological theory, but to solve a mystery. This is a narrative mechanic found in millions of fairy tales, novels, movies and documentaries: we are so accustomed to this pattern that we cognitively process it with extreme fluency, increasing the “aesthetic” pleasure inherent in the enjoyment of the content.

Canonical narrative scheme

Canonical narrative scheme

There is a vast literature showing that, in an infinite variety of fields, stimuli processed with difficulty tend to be evaluated negatively, while the evaluation of stimuli of easy cognitive processing undergoes - conversely - a positive influence. A few examples: stocks with hard-to-process names are considered less competitive in the marketplace (Alter and Oppenheimer, 2006); aphorisms using easy-to-process linguistic forms tend to be considered truer (McGlone and Tofighbakhsh, 2000); even, simply being repeatedly exposed to an assertion increases the ease with which it is processed and, consequently, the likelihood that the assertion will be considered true (Reber and Unkelbach, 2010), which come to think of it is the principle of political slogans or advertising claims, no more and no less.

Jenny Holzer, Slogan

Jenny Holzer, Slogan

Art, of course, has also been the subject of study. Indeed-to pick up on the incipit-it all stems from there. Despite the fact that Wertheimer never had any enlightenment from looking at a Kandinsky painting, throughout the 20th century aesthetics and psychology were repeatedly intertwined in an attempt to find a scientifically accurate answer with respect to how we evaluate and perceive artistic “beauty.” One of the key experiments in understanding Processing Fluency Theory was conducted by Rolf Reber and his colleagues in 2004. The study involved a sample of undergraduate participants, chosen for their familiarity with aesthetic evaluation tasks and willingness to participate in psychological studies, who were shown a set of images designed to vary in complexity. The experiment was divided into two main phases: in the initial phase, ease of processing was manipulated through visual contrast. Some stimuli were presented with high contrast (to make them more or less visible); concurrently, the time of exposure to the stimuli also varied: some participants saw the stimuli for a short period, others for a longer period.

In the tests, replicated with numerous different groups to ensure the reliability of the experiment, strict controls were implemented to ensure that other subjective factors, such as individual preference for certain types of images, did not influence the results. What emerged? That stimuli presented with high contrast (and therefore easier to process) were rated as significantly more pleasant than those with low contrast. Similarly, subjects found stimuli exposed for longer periods more pleasurable than those exposed for shorter periods. In addition to the aesthetic ratings, participants were asked to judge their ease of processing the stimuli to see if they perceived differences in fluency: surprisingly, almost all people were conscious of their cognitive activity.

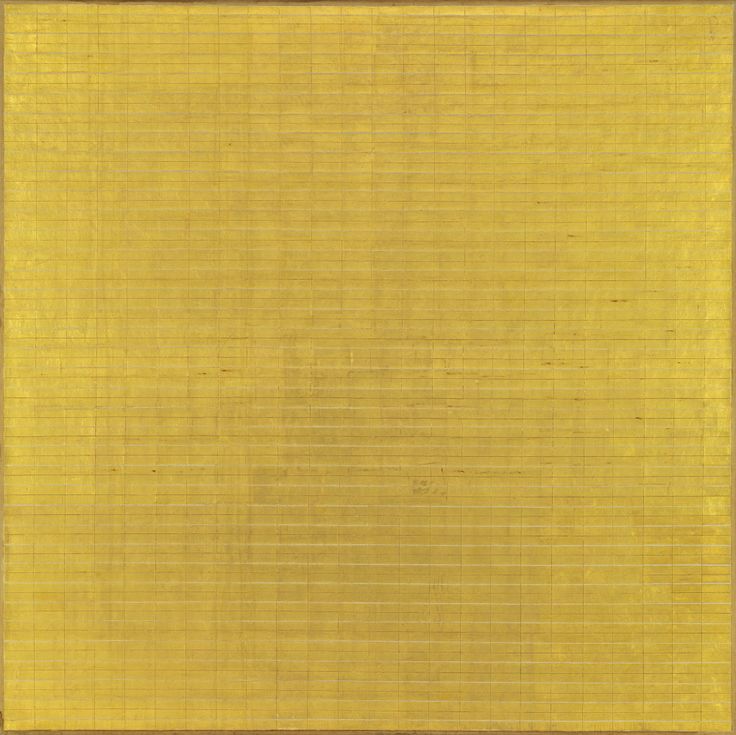

A superficial reading of the experiment may lead us to think that the perceived “beauty” in a work depends on its simplicity. Not so: complex works can be widely appreciated; PFT suggests only that they require a different kind of cognitive engagement, often supported by an understanding of context or prior knowledge of art. Every artistic language possesses a grammar that, while seemingly complex, becomes more pleasing as the viewer becomes accustomed to interpreting its inner workings “code.” This concept was explored in 2005 by Halberstadt and Winkielman, who found that ambiguous visual stimuli become more pleasurable when repeated. Repeated exposure reduces the cognitive effort required to process the information, increasing familiarity and perceived pleasantness.

There is, of course, much more. According to the model of visual aesthetic processing proposed by Leder, Belke, Oeberst, and Augustin, exposure to an artistic stimulus provides the perceiver with a challenging situation for the mind: in practice, in order to overcome the perceptual obstacle, the observer must cognitively classify, understand, and master the work. It is success in this process that provides the motivation to seek further exposure to artistic stimuli. Over time, this kind of motivation increases interest in art in general: this explains why some people shy away from art enjoyment, while others become increasingly passionate about it. For Kubovy, moreover, the emotions that characterize the pleasures of the mind, of which aesthetic pleasure is necessarily a part, emerge when our expectations are betrayed, and errors in “anticipations” are transformed into a stimulus for the search for new interpretations. This, at least in part, explains the planetary success of the avant-gardes and all the “rupture” movements that have followed throughout history.

Anish Kapoor, Sky Mirror

Anish Kapoor, Sky Mirror

Thus, while we value stimuli that are easy to process, we also value stimuli that present a cognitive challenge to both our sensory perception and our understanding. To read this dichotomy from a bioevolutionary perspective, both behaviors possess a fundamental adaptive quality. The advantage in appreciating easy-to-process stimuli lies in the fact that familiarity is often associated with “safety,” and the perceived ease of processing is often indicative of its success. Conversely, the positive effect of appreciating stimuli that are difficult to process is that it induces us to engage in exploratory behavior, which is essential for the acquisition of new knowledge.

Yayoi Kusama, Infinity Mirrored Room - The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away

Yayoi Kusama, Infinity Mirrored Room - The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away

Art, after all, is a real “gym” for our minds. And the theory of processing fluency-complementary, not opposed, to the pleasure inherent in cognitive challenges-demonstrates that we can “train for complexity.” In a historical period characterized by an information overdose, where the proliferation of slogans and fake news can direct political and social choices of fundamental importance, aesthetic perception is rediscovering itself as a crucial factor in consciously dealing with an infosphere saturated with stimuli, among which it is very difficult to find and rediscover real “value.” Everything seems to be reduced to sterile background noise, incapable of producing meaning: on the contrary, however, art can still do so. Through aesthetic enjoyment we can learn to embrace the complexity of our reality and, little by little, move nimbly in a hyper-connected, hyper-complex world. Provided, this goes without saying, that art really becomes part of our lives again.

Creative, teacher and expert in visual culture, Alessandro Carnevale has worked on TV for several years and has exhibited his works all over the world. In 2020, the Business School of Il Sole 24 Ore included him among the five best Italian content creators in the artistic field: on social media he deals with cultural dissemination, covering a wide spectrum of disciplines, including the psychology of perception, semiotics visual, aesthetic philosophy and contemporary art. He has collaborated with various newspapers, published essays and written a series of graphic novels together with the theoretical physicist Davide De Biasio; he is the artistic director of an open-air museum. Today, as a consultant, he works in the world of communication, training and education.