Art is dead. Dead and buried.

For some 200 years, it seems, at least if you read Hegel. And with him the multitude of critics, philosophers and intellectuals who have taken up his words - sometimes misrepresenting them, and not a little - to issue an apocalyptic sentence that sounds so good it has become a slogan.

Here, 'slogan': a dangerous term, which alone should be enough to warn anyone who masters a little complexity. Enough slogans, then (which sounds a lot like a slogan, I realise) - let's leave those to politics and marketing, and try to analyse the meaning ofnwords for a moment.

From Truisms (1977–79), 1982 Installation: Messages to the Public, Times Square, New York, 1982 © 2024 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY Photo: John Marchael

From Truisms (1977–79), 1982 Installation: Messages to the Public, Times Square, New York, 1982 © 2024 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY Photo: John Marchael

Art is dead, we said. Good. If so, there should be a corpse somewhere on which to perform an autopsy. The circumstances of the alleged death are unclear, and open up further questions: did Art die of natural causes? Or was she murdered? And by whom? Very difficult to establish without a body to study. So complex that some might begin to doubt the very existence of this phantom art.

The equation, after all, is simple and straightforward: if art is dead, and it would seem so, given that we have been reading about it for two centuries, then art is something perfectly definable, something that everyone knows a priori. Indeed, this is precisely the coyness with which Benedetto Croce summed up his concept of Aesthetics: “art”, he said, ”is what everyone knows exactly what it is”. And in these words echoes a common and collective feeling that gives art its own, autonomous dimension, which, indeed, is spontaneously recognised by anyone who encounters it. Mystery solved, then? Not quite.

Giovanni Anselmo, Invisible

Giovanni Anselmo, Invisible

On re-reading the chaotic trajectories of contemporary art - another ambiguous word, given that every art form of mankind has been contemporary for those who have lived through a certain historical period - and the difficult relationship of the public with such artistic manifestations, the question becomes increasingly complicated. There is very little that is spontaneous in the artistic recognition of a Picasso or Warhol, just to give two illustrious examples. Now, not having the pretension here to go back over a hundred years of the avant-garde, nor to go into a cloying art history lesson, the only thing I can invite you to do, at the moment, is to think once again about words.

When defining the rupture of the order promoted by the artists of the early 20th century, we often come across a rather evocative phrase: digested avant-garde. The term is perfect for describing the processing phase necessary for the re-absorption of the avant-garde revolutionary movements within that collective feeling mentioned earlier. The digestion may be more or less long, but eventually any artistic 'transgression' loses its shocking (and repelling) value until it is perfectly integrated into the art market and, little by little, into the collective aesthetic imagination.

Damien Hirst, The Physical impossibility of Death in someone living

Damien Hirst, The Physical impossibility of Death in someone living

Galleries and museums all over the world are filled with excrement and rotting corpses.

Artist's shit is sold by the pound, Hirst's carcasses are auctioned for millions. Thus, perhaps definitively, the idea that the work of art possesses value in itself dissolves: there is no formal characteristic sufficient to create an ontologically valid distinction to separate art from non-art. This is the lesson of the entire 20th century: a century - a century! - of theoretical and conceptual experimentation that we should by now have largely digested.

We have to take shit from shit, in short. And change the Crocian paradigm: 'art', in the words of Dino Formaggio, “is everything that men decide to call art”.

I honestly can find no better summary to describe the entire artistic production of any historical era. Do you know why? Because in that decider the necessarily relational dimension of any form of aesthetics, contemporary or otherwise, immediately emerges. Art is always a communicative system based on the relationship between artist, work and viewer. It is we, all of us, who unequivocally arbitrarily ascribe the symbolic, cultural and aesthetic value of an object we choose to call "work".

The relativistic drift of such an assumption is just around the corner, I make no secret of it. To say that "art is all that men call art" is, first of all, to accept the assumption that art can be totally useless. If, on the other hand, we believe that art has a purpose, we implicitly admit that there is a scale of values in art that makes works more or less valuable. Which I certainly agree with, but who decides that? Who chooses what is good art?

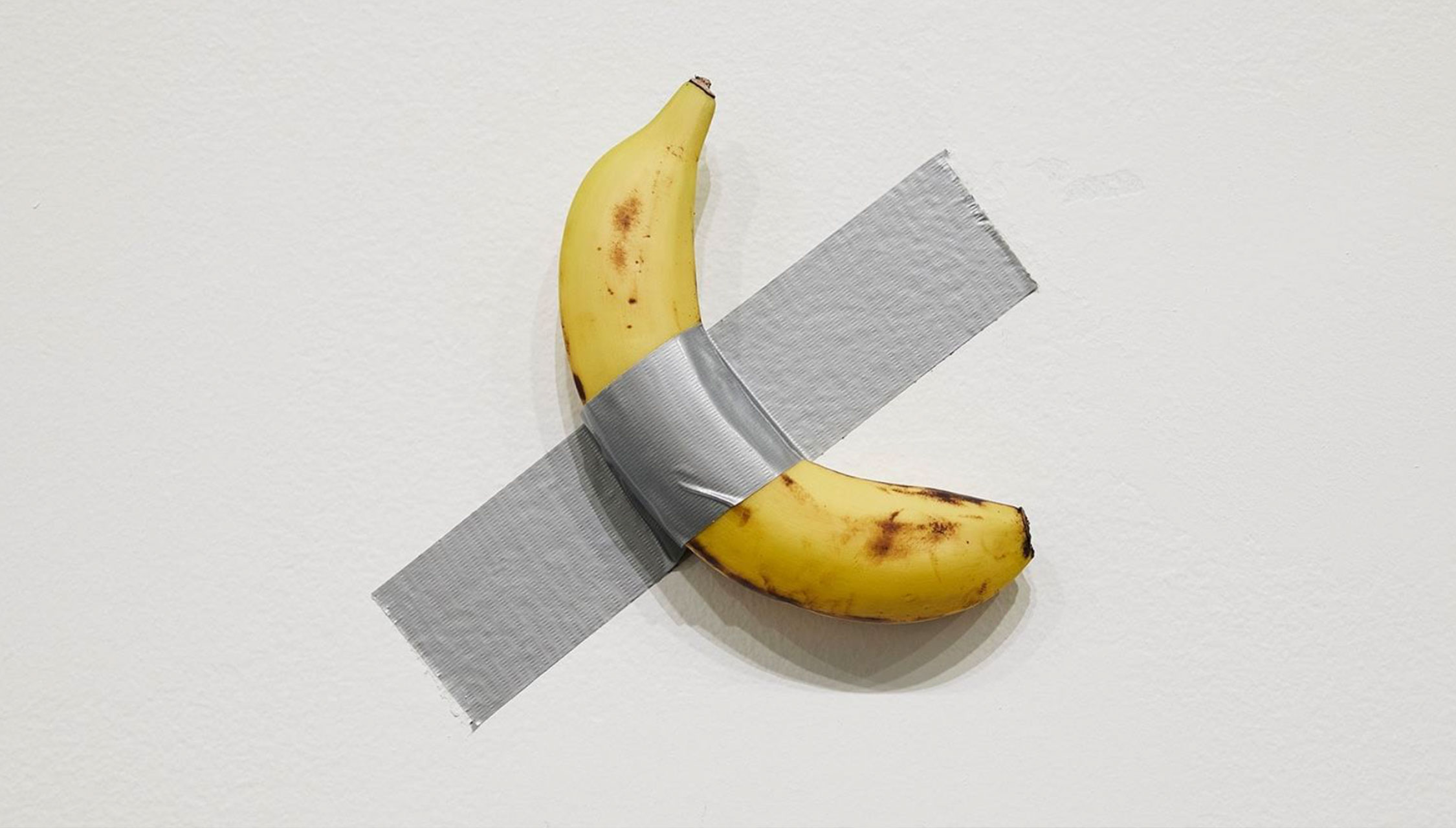

Again: us. It is not enough for me to call an object art for it to become art. There must be other people willing to do the same thing, and they must be equally willing to actively acknowledge its value. With all the short-circuits that this assumption entails. I, or any other guy, do not have the same decision-making power as an established artist or critic. When Maurizio Cattelan tapes a banana to the wall and a collector spends $120,000 to buy it, the whole political dimension of the Art System clearly emerges.

Mind you, I am not using the term "political"in a derogatory way. Cattelan's Comedian is an eloquent synthesis of the intersubjective process that determines the value perception of a work: the general public is outraged when reading the news of the banana purchase, the artist (who has made provocation his stylistic hallmark) smiles, the buyer and the gallery owner are happy to have closed the deal. Art is also market, whether we like it or not. Art, again, is a political process, in which we are all invited to participate. And if we remove ourselves from the debate, someone else will decide for us. However, the definition of Formaggio, which I defend, should not slip into a permissive laxity that demeans art itself: on the contrary, it should stimulate the activation of theoretical debate and a relentless search for new creative solutions. It should at least reaffirm to the public its own strength, determining a conscious and less passive fruition: all far more difficult and certainly more "useful" enterprises than claiming to establish what is or is not art, creating delimitations that will always be questionable after all.

The misunderstanding of the Hegelian prophecy of the death of art must finally be disproved, or at least corrected, once and for all. The philosopher, at the turn of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, spoke of the decreasing centrality of art in the feeling of successive historical ages, without ever expiring in such a definitive judgment. Art is not dead: rather the human beings who keep it alive have been replaced. But replaced by whom? By an audience divided into two souls. A minority and (sometimes) smug niche of enthusiasts, insiders and collectors, directly involved in the world of contemporary art; and a silent mass of disillusioned and disinterested, who still have not digested Duchamp's ready-made or Fontana's cut-outs. Unwittingly, by removing themselves from the collective debate, the latter offer enormous decision-making power to the former, who - even to the tune of million-dollar checks - forage a System increasingly distant from daily life, eliminating any perception of the value of art, beyond the exorbitant figures that are occasionally relaunched in the newspapers after a few auctions at Christie's.

When was the last time contemporary art was even discussed in a bar? Maybe in 2019: again, I think of Cattelan's banana. David Datuna peeled one off and ate it in public, despite its prohibitive cost. He became known on Instagram as the hungry artist: the work, after all, was meant to be replaceable. A performance - I'm sure - that pleased the vast majority of people who perceived no artistry in Comedian.

In contrast, the "Just Stop Oil" activists daubing a Van Gogh (or rather, the glass protecting the work) seemed to greatly irritate the crowds, despite the fact that the cause for which they are fighting is shareable and quite urgent. Not only that: on a symbolic level, pouring paint on the glass that protects the masterpieces of art history recalls the impossibility of artistic creation in a world moving toward self-destruction. If each artist lays down in the work the hope of surviving himself, the public - here really understood as humanity, in its entirety - should at least worry about securing a future to enjoy such creations. Yet people are outraged, proving that art still possesses enormous symbolic, cultural and cultic value.

Here, let's take the daubed Sunflowers: who decided to inscribe Van Gogh's art among the World Heritage? We did. Humanity itself. And it was certainly not an easy process. Vincent sold only one painting in his entire life. For years his works have been widely despised: the Sunflowers are still the same, it is the audience that has changed, quite apart from the political process (in the most genuine sense of the term) that has allowed the work to absorb and simultaneously emanate that layering of affective, formal, qualitative, mythic and symbolic meanings that we perceive to have been violated by the soup thrown by the activists.

Art is not dead. Certainly, however, it is agonizing. It affects people's lives very little. Who, perhaps out of exhaustion, choose not to decide -- to quote Dino Formaggio one last time - what to call art. Is it possible to reverse the paradigm? I believe it is. Art must invade the present, besiege existence, preside over unexplored spaces. It must return to people's lives. Because untethered from life, art is at best nothing more than a mere object.

Cover image: Maurizio Cattelan, Comedian

Creative, teacher and expert in visual culture, Alessandro Carnevale has worked on TV for several years and has exhibited his works all over the world. In 2020, the Business School of Il Sole 24 Ore included him among the five best Italian content creators in the artistic field: on social media he deals with cultural dissemination, covering a wide spectrum of disciplines, including the psychology of perception, semiotics visual, aesthetic philosophy and contemporary art. He has collaborated with various newspapers, published essays and written a series of graphic novels together with the theoretical physicist Davide De Biasio; he is the artistic director of an open-air museum. Today, as a consultant, he works in the world of communication, training and education.