THE MURDER OF FRANCESCA ALINOVI

A brilliant and controversial art critic, the behind-the-scenes of DAMS, her bond with emerging artists. The murder that shocked the city of Bologna in the 1980s.

It’s the morning of January 23, 1997, in Barcelona. The weather is milder than in other European countries this time of year, perhaps thanks to the sea nearby, whose currents carry away the winter dampness. We’re in the Penuela neighborhood, where the steep streets rising from the Manzanares to the Puerta del Sol echo with the sounds of late-night bars, the clinking of beer glasses, and the aroma of tapas that fills the air. In this corner of the city—where poverty and the dreams of pseudo-artists intertwine—a man walks: cigarette in mouth, sunglasses on, tall and slender posture. His fine, straight hair just brushes the collar of his shirt. He’s thinking about his morning, unaware that in that very moment, his life is about to change forever.

Suddenly, a voice interrupts him: “Documentación, por favor.” His passport is in order, nothing to worry about. But the voice continues, sharp: “Nombre y apellidos, por favor?”

The man begins to feel suspicious, but his voice remains calm. “Giampiero Contini,” he replies. He doesn’t have time to say anything else.

Immediately, his hands are seized, his arms bent into an unnatural position. Caught. Arrested.

The police know that is not his real name—and after years of investigation, they’ve finally found him.

Thus ends a story that began on June 15, 1983, in Bologna.

But let’s take a step back.

Francesca Alinovi

Francesca Alinovi

Bologna, Saturday, June 11, 1983, around 6:30 p.m.

A large crowd has gathered at Galleria Neon, the exhibition space founded and directed by Gino Gianuizzi—a true hub of experimentation, where many artists we know today exhibited at least once. That evening, two shows are opening, both curated by Francesca Alinovi, a young curator making her way in the treacherous world of contemporary art. Her hair is tousled, as always; she’s wearing black leather pants, and her body radiates a magnetic boldness that’s clear to anyone watching her.

People are chatting, drinking, laughing. In Bologna, when Francesca organizes something, the crowd always shows up—maybe because of her DAMS lectures, which some describe as real happenings, or maybe for her uncanny eye for discovering emerging artists, or those pieces of art criticism that strike and stir the soul.

Whatever the reasons, one thing is certain: she’s a rare, magnetic being.

That night is a celebration—time to revel in the success of the exhibitions.

Francesca is alive, punk—not just in her look, but in her way of facing life. And so, everyone dances with her until the early morning. Tired and giddy from the night’s buzz, they head home. Francesca hosts a few artist friends.

In Bologna, in June, it’s already warm enough to sleep with the windows ajar. Sure, there’s no sea here—but this isn’t Barcelona.

The alarm doesn’t ring too late on that Sunday. Then a shower, to wash off the remnants of the night. Francesca returns to her room and stands in front of the closet.

“How do you choose the clothes to wear for your final hours of life?” She doesn’t know, and few in life ever bear the fear—or privilege—of knowing.

Unaware of her fate, she picks a striped shirt with a vest over it, white pants, and patent leather boots. She looks in the mirror, smiles. She likes what she sees. A glance at her wrist—her Rolex. She never takes it off. Always on her left wrist, a faithful ally against any missed appointment.

She’s late. Francesco is probably already waiting.

“Or maybe being his usual idiot self, he’s not ready either.”

Francesco. Francesco Ciancabilla. Some call him her protégé. They shared a complicated, difficult relationship.

A year earlier, in her diary, Francesca wrote:

“Francesco, a dark-haired alter ego (...), a love straight out of a Pasolini story. Love, folklore, romantic painter, a boy (...). He reminds me of my barefoot, gypsy childhood self. (...) He’s the male version of me—who I wish I could’ve been. (...) I like him as if I’ve never had a crush before.”

But time changes things. That cursed time.

“What I feel goes beyond infatuation. I want to attack him.”

But a few months before the murder, her writing turns bitter:

“The eternal nothingness of a relationship that can never be. I kissed him, caressed him, but he gave me nothing.”

And again:

“A historic date—from February 13, 1981, to March 9, 1983. Stop. I’ve stopped loving him.”

“Hooray, hooray, for the first time I saw him as a moron.”

Francesco also lives in the center of Bologna, with a roommate. Both use heroin. For Francesca, this is devastating. It angers and worries her. Every time he injects that “shit” into his veins, something in him dies.

Still, she sees him for what he could be: a great artist. She discovered him during her classes at DAMS. She had an eye, a sharp instinct. She immediately sensed the boy had talent.

But with that talent came passion. Unrequited love. Maybe only hinted at, maybe misleading, but eventually rejected.

And Francesca suffered. She withered.

“Saying I’m unhappy doesn’t even begin to describe my unhappiness. To keep loving Francesco when he cannot love me. Alone, alone, alone. Me, alone. Me, loving and unloved.”

Francesco Ciancabilla

Francesco Ciancabilla

Within a year, everything changed. Francesca acted erratically. There were arguments. Even physical altercations—bruises that should have been warnings, signs that what they shared—whatever it was—wasn’t love. But judging from the outside is always too damn easy.

Now, he’s there. In front of her. At the door.

And now, nothing makes sense anymore.

They walk back to Francesca’s place. They'll spend the whole afternoon together. Then he has to catch a train to Pescara to visit his family. He invited her, but she declined.

That’s how this Sunday will go.

At 7:30 p.m., Francesco leaves the home of the woman he always called his best friend and heads to the station.

It will be the last time they see each other.

Monday. The DAMS lecture hall is packed with students. They’re waiting for Professor Alinovi’s class. The customary academic quarter passes—she doesn’t show. Tuesday comes and goes too. That Rolex, once ticking through Francesca’s countless appointments, now seems to have stopped.

Three days have passed since her sister last heard her voice on the phone. The worry mounts.

On the morning of June 15, family and friends alert the fire department. They go to Via del Riccio 7, climb to the second floor, and—with the help of the carabinieri—break down the door.

Francesca is there. On the floor. Still wearing her white pants, vest, striped shirt, and boots. Her body bears dozens of wounds: 47 stab marks. Only one, however, was fatal.

Two pillows cover her face—they were used to smother her, to steal her last breath.

She bled out and suffocated. A slow, cruel death.

The wounds are shallow. Investigators are puzzled, suggesting the weapon was small and wide—like a cheese knife.

Nothing is missing. The place is tidy. No signs of forced entry. Francesca knew her killer. She let them in. Willingly.

Her friends say she was cautious—she always checked the window before opening the door. No way she let in a stranger.

But in the bathroom, on the windowpane, a message appears:

“YOUR ARE NOT ALONE ANY WAY”.

An obvious grammatical error. But the meaning is clear: “You are not alone, anyway.”

A haunting, ambiguous phrase: is it a threat or a comfort?

Strangely, none of the artists who stayed over that Sunday morning remember seeing it. Unlikely, since the window reflected clearly in the bathroom mirror.

It would later emerge that the same phrase—"Your are not alone any way"—had been written days earlier by a friend on the mirror, a gesture of support during a tough time.

The theory is it was erased and rewritten—this time on the glass. Maybe now with a new meaning. But who did it?

Francesco is quickly found and questioned. He was the last person to see her alive. He pleads innocence (and maintains it for life): says he left while Francesca was still alive.

A handwriting analysis rules him out as the author of the bathroom message. But what about everything else? What happened that afternoon?

On that Sunday, before Francesco left for the train, Francesca made several phone calls to her sister and some friends. She said she wasn’t alone.

Suspicion falls on him.

What follows is a flurry of forensic analyses.

But it’s the '80s—technology is limited, margins of error are wide.

The autopsy and the Rolex (a self-winding model that runs only with wrist movement) both place the time of death before Francesco left the house.

Too many clues point to him: the unreciprocated love, the fights, even over selling his paintings—that as the artist said — always shoud have been more to quickly earn money, his drug use.

Everything seems to pin him down.

But is he really the killer?

There’s no hard evidence. Witnesses who saw him leave and reach the station describe him wearing the same clothes—analyzed by investigators and found free of any blood. No scratches or wounds on his body—odd, if he had killed Francesca with that knife.

No concrete proof, only a pile of clues.

So, he’s held in pre-trial detention. Francesco spends two years in jail, awaiting trial.

On January 31, 1985: acquitted for lack of evidence. Francesco is released.

Less than a year later, on December 3, 1986, the Court of Appeals overturns the verdict: guilty of voluntary manslaughter. Fifteen years in prison, sentence reduced due to a psychiatric evaluation.

The report states that if Francesco committed the murder, it was in a state of temporary insanity—a fit of rage (that’s the phrase, right?).

A man kills a woman. An act rooted in patriarchy and power imbalance.

But it’s the '80s, and those words don’t exist in the justice system’s vocabulary.

Was justice served?

Hard to say. Maybe the Court had its reasons. Francesco’s actions—disappearing, crossing borders, living as a fugitive for ten years—validated their doubts.

Until that day in Barcelona, January 23. Interpol found him during a probe into fake documents. He was hiding behind a false identity.

After serving his sentence, he was released in 2006.

Francesco Ciancabilla has always claimed he’s innocent.

In cases like these, the victim often fades to the background—becomes a figure to sanitize, to idealize.

But Francesca Alinovi wasn’t like that. She wasn’t afraid to get her hands dirty in the prose of the world. She dove into society’s veins: watching, seeking, suffering, struggling.

To many, she was one of the most promising Italian art critics of the past forty years.

She was murdered at 35, while working as a researcher in Aesthetics at DAMS in Bologna.

A curator and theorist, known for her fieldwork, she had been assistant to Renato Barilli, one of DAMS’ founders.

After several trips to New York, she introduced Keith Haring to the Italian art world. She wrote for magazines like Flash Art, Domus, and more.

She was a pioneer in championing artistic avant-gardes and the blending of painting, theater, sculpture, music, and comics.

Keith Haring, Untitled (Painting for Francesca Alinovi), 1984.

Keith Haring, Untitled (Painting for Francesca Alinovi), 1984.

In New York, she immersed herself in the underground art scene, which deeply shaped her curatorial vision. Among her most important exhibitions: Pittura Ambiente (1979), and posthumously, Arte di frontiera: New York graffiti (1984). She was also the theorist behind Enfatismo, an art movement born around Bologna’s Galleria Neon.

Her death is a profound loss for the world of contemporary art.

A murder that never found a clear truth, leaving us lost in smoke—of contradictions, suspicions, and perhaps, tragically, gendered violence.

Though I never met her—by age, I couldn’t—I encountered Francesca at university, through old exam readings, discovering her words with curiosity and admiration.

Beyond the blood, pain, and possible brutality that marked her death, I like to remember her with this story:

Keith Haring once wrote in his diary that the best interview of his life was with Francesca Alinovi—for the empathy and care she showed him.

To thank her, he dedicated one of his most beautiful works: Untitled (Painting for Francesca Alinovi), 1984.

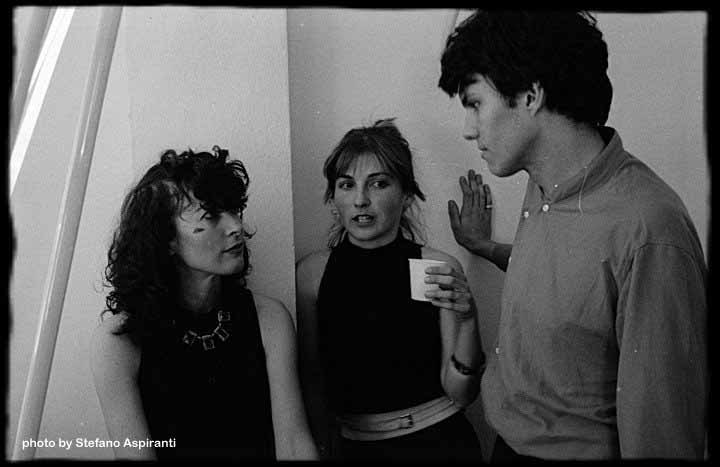

Cover Image: Francesca Alinovi e Francesco Ciancabilla - Photo by Stefano Aspiranti

Alessio Vigni, born in 1994. He designs, edits, writes and deals with contemporary art and culture.

He collaborates with important museums, art fairs and artistic organisations. As an independent curator, he works mainly with emerging artists. He recently curated “Warm waters” (Rome, 2025), “SNITCH Vol.2” (Verona, 2024) and the exhibition “Empathic Dialogues” (Milan, 2024). His curatorial practice explores the relationship between the human body and the social relationships of contemporary man.

He writes for several specialised magazines and is author of art catalogues and podcasts. For Psicografici Editore he is co-author of SNITCH. Dentro la trappola (Rome, 2023). Since 2024 he has been a member of the Advisory Board of (un)fair.