Prison Times: the design of penal spaces in Milan

How Dropcity’s exhibition project turns the prison into a subject of cultural reflection — blending social critique, design objects, and invisible architecture.

When I lived in Venice—referring to the island, not the mainland—during my first year at university, I had a small single room in a shared apartment just steps away from the city’s male prison. On Saturdays, while hanging clothes out the window, I would sometimes hear the shouts or cries of inmates’ relatives and friends who had come to greet them and tried to strike up a conversation with those inside. Venice’s prison is unique in this regard: some of its cells face the fondamenta (a Venetian term for the walkway running along a canal or rio), and this makes it easier to establish communication between inmates and people outside. They can see you, but you can’t see them. My former flatmates, or any women passing along that fondamenta, would often receive unsolicited comments or catcalls from the inmates. An unusual dynamic emerged between that prison and life outside its walls. Unique, even.

Santa Maria Maggiore Men’s Prison, Venice

Santa Maria Maggiore Men’s Prison, Venice

I often found myself wondering what life was like inside: what the spaces were like, the cells, the social dynamics within. In the less touristy bacari (a type of traditional Venetian tavern), on certain evenings, I encountered people who had "stayed" in Venice’s prison. Some I trusted to be telling the truth; others, I could verify through a particular detail. On their hands—or on other easily accessible parts of the body for self-tattooing—I’d sometimes spot a shape made up of five dots: four forming a square, and one in the center. Some inmates, particularly those with a few years of experience behind bars, would tattoo this symbol on themselves while in prison. The square, which sometimes appears as a continuous line, represents the cell; the central dot stands for the inmate, locked within those four walls. A kind of testimony to their past.

Few opened up in any real depth, but some, emboldened by one too many spritzes, let a few details slip. A few of these men described the conditions in the Venice prison’s cells—places dominated by mold and rats. Only the cells facing the fondamenta—those from which inmates could call out to friends, family, or wives—were considered “better,” but they could only be obtained through a “nonstandard” procedure.

One man once said: “You’ve got to take a long ride to get one of those upper, sunny cells.” I’m simply reporting what he told me, with no evidence to support it. But with the phrase “take a long ride” that former inmate was alluding to immoral acts that I prefer not to detail, in order to avoid censorship or warnings from those associated with the facility.

This introduction, which I felt important to include at the beginning of this piece, highlights the pitiful state of Italian prisons. Antigone, a human rights organization, published a year-end report on the state of correctional institutions in 2024 with alarming data. As of December 16, 2024, the prison population had reached 62,153, against an official capacity of about 47,000.

This brings the overcrowding rate to 132.6%, with critical peaks in institutions like San Vittore in Milan (225%) and Canton Mombello in Brescia (205%). The real capacity has decreased over the years due to neglect and lack of maintenance, rendering the facilities increasingly dilapidated and unlivable.

The report also highlights a rise in critical incidents: 88 suicides were recorded in 2024—a tragic record—and a total of 243 deaths. Incidents of self-harm, suicide attempts, and assaults are also on the rise. Although there are some positive signs in the areas of prison labor and vocational training, they remain insufficient to offset the overwhelmingly negative picture. For instance, training opportunities reach only 6% of the prison population nationally, with significant regional disparities. And it’s not just the inmates—between 2011 and 2022, 78 prison officers took their own lives. Yet these issues seem to be of little concern to our political class, which continues to worsen the situation with increasingly repressive security bills. What many fail to understand is that investing in prison systems, improving conditions, and applying incarceration that is not punitive but rehabilitative and geared toward social reintegration, is not a sign of weakness, but of strength and civilization.

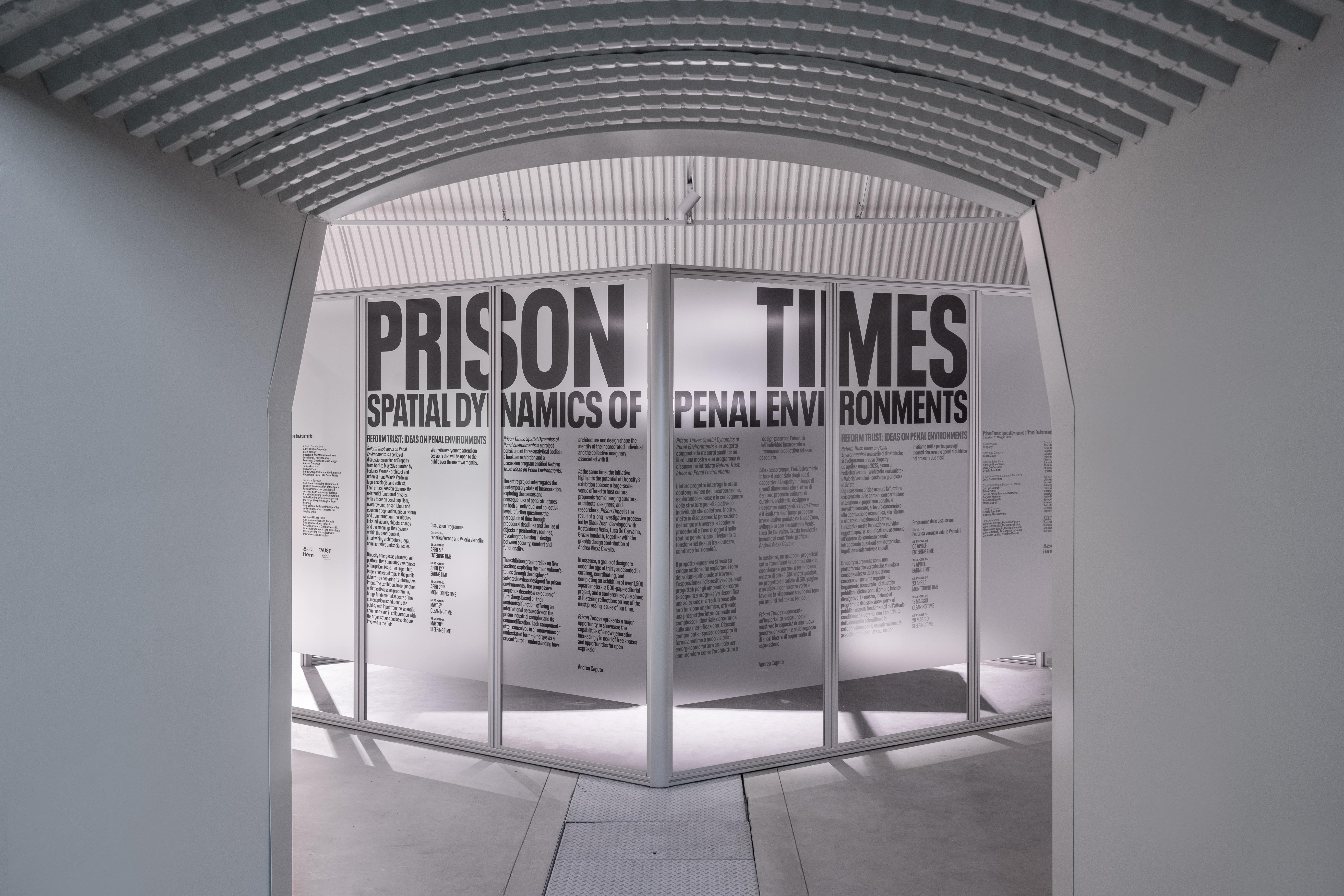

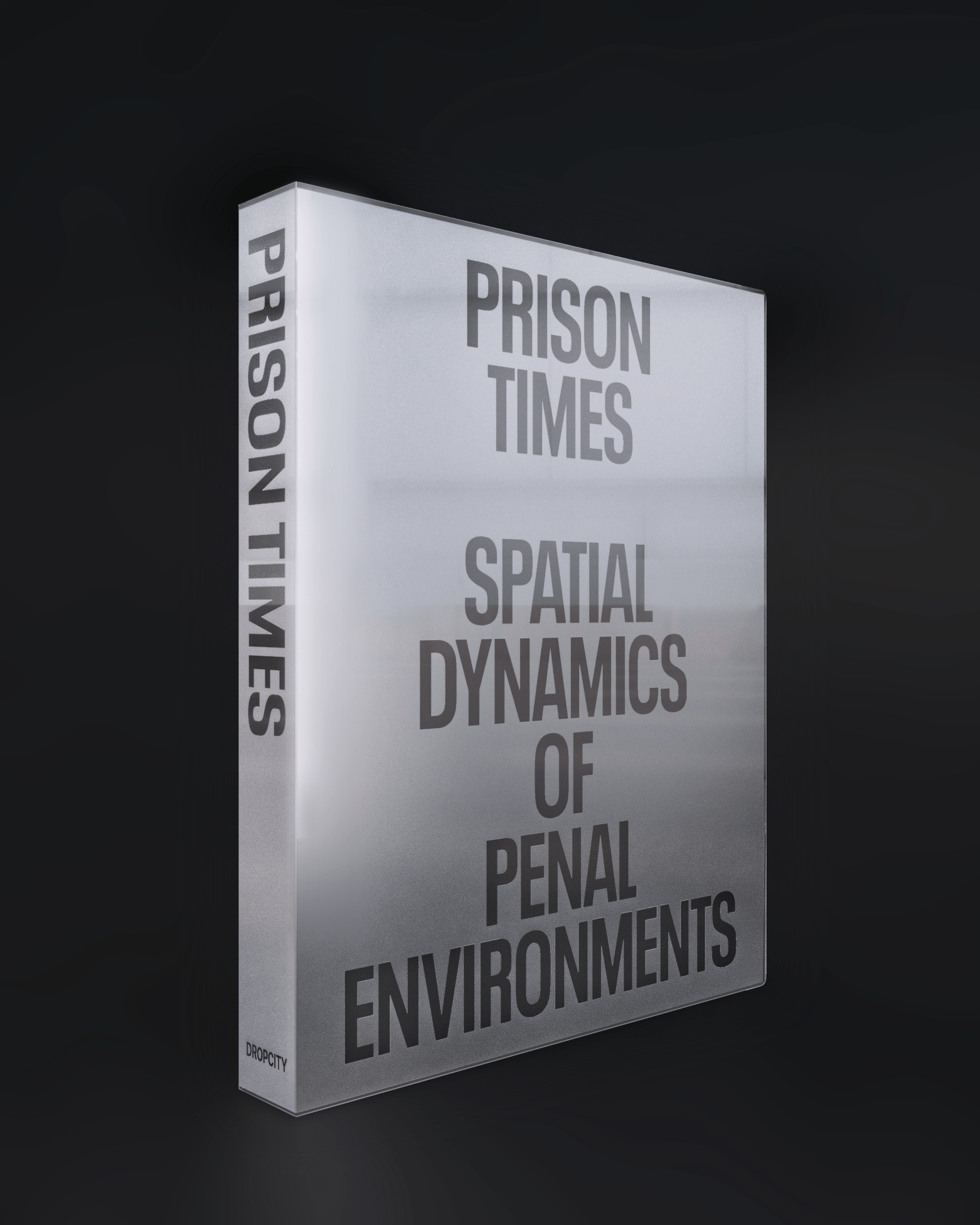

Why am I writing about prisons in a magazine dedicated to art and culture? The answer is simple: I want to introduce you to the most interesting exhibition I’ve had the pleasure of visiting in 2025. It’s Prison Times: Spatial Dynamics of Penal Environments, an exhibition still on display in Milan, hosted in the beautifully repurposed spaces of Dropcity. Opened during the 2025 Fuorisalone, the exhibition runs until May 30. The project is composed of three parts: a book, an exhibition, and a program of talks titled Reform Trust: Ideas on Penal Environments. The entire initiative, produced by Dropcity, investigates the current state of incarceration, exploring the causes and consequences of penal structures both individually and collectively. It represents an initial synthesis of testimonies about prison environments in Italy and around the world.

The exhibition acts as a visibility project: it breaks the physical and legal barriers that confine prison furniture to inaccessible spaces, hidden from everyday view, and brings them into a public arena, prompting collective critical reflection. Its aim is to spark a dialogue that makes us question the role of architecture and design as practices that can contribute to both punishment and rehabilitation mechanisms—and to the successes or failures of the prison system.

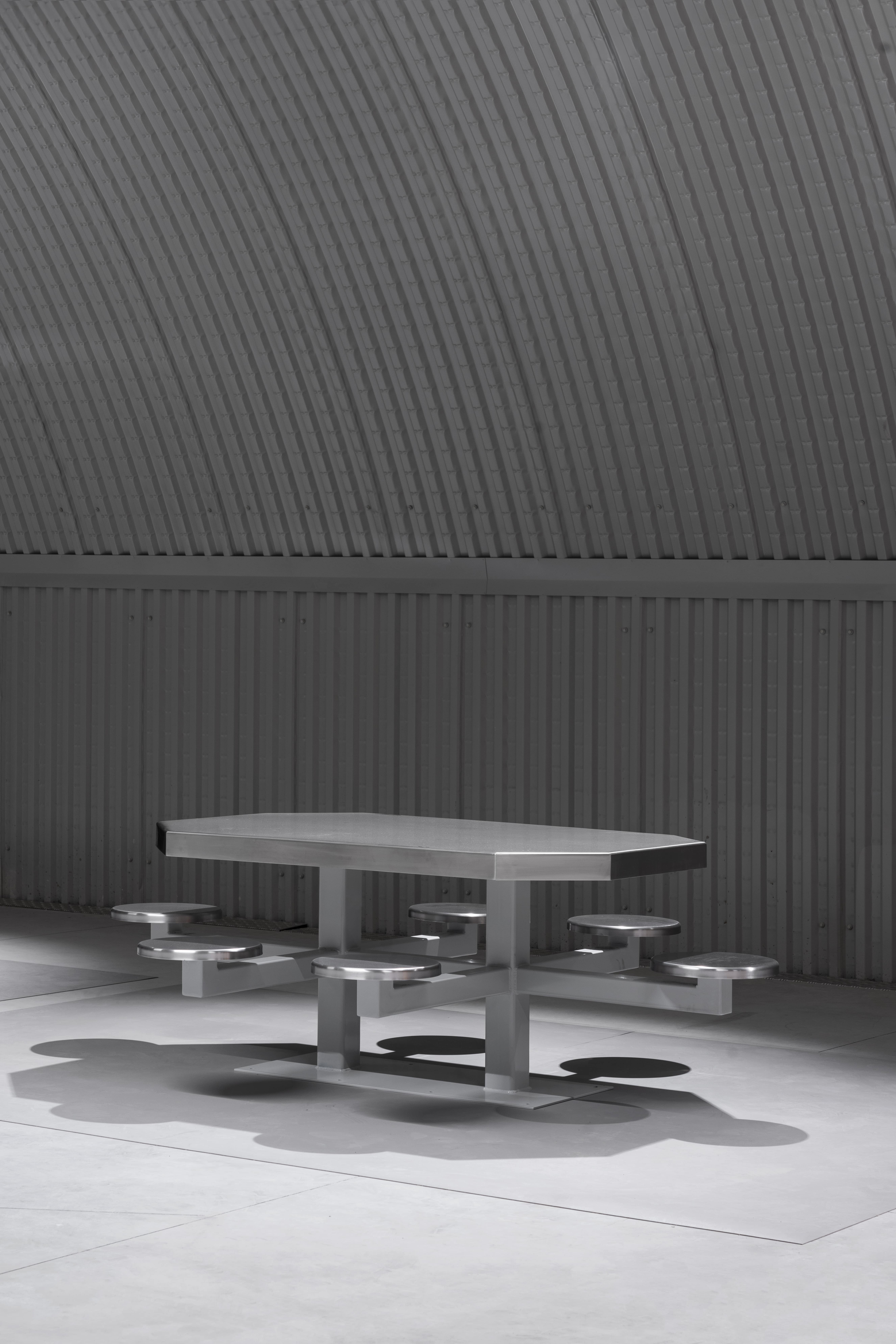

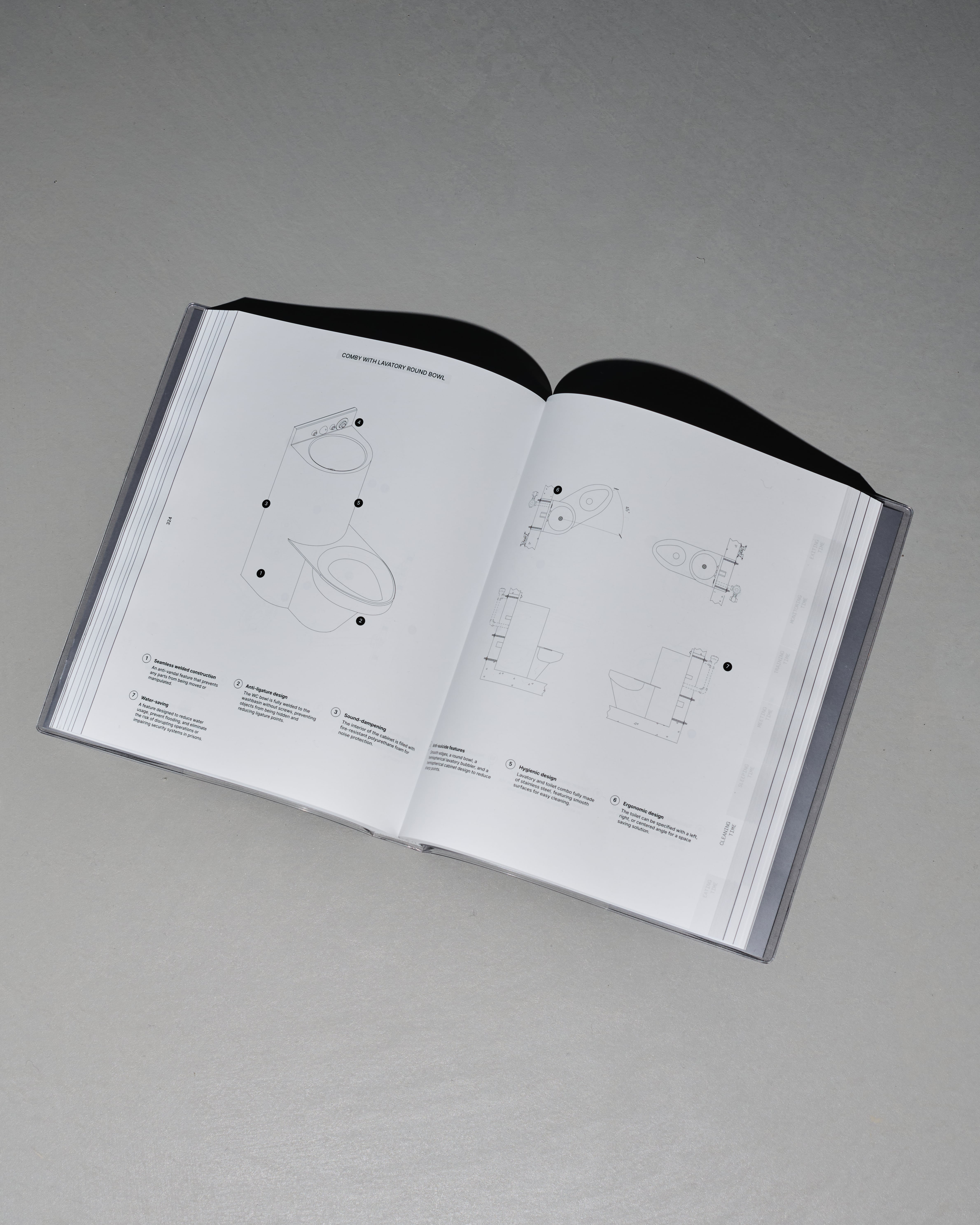

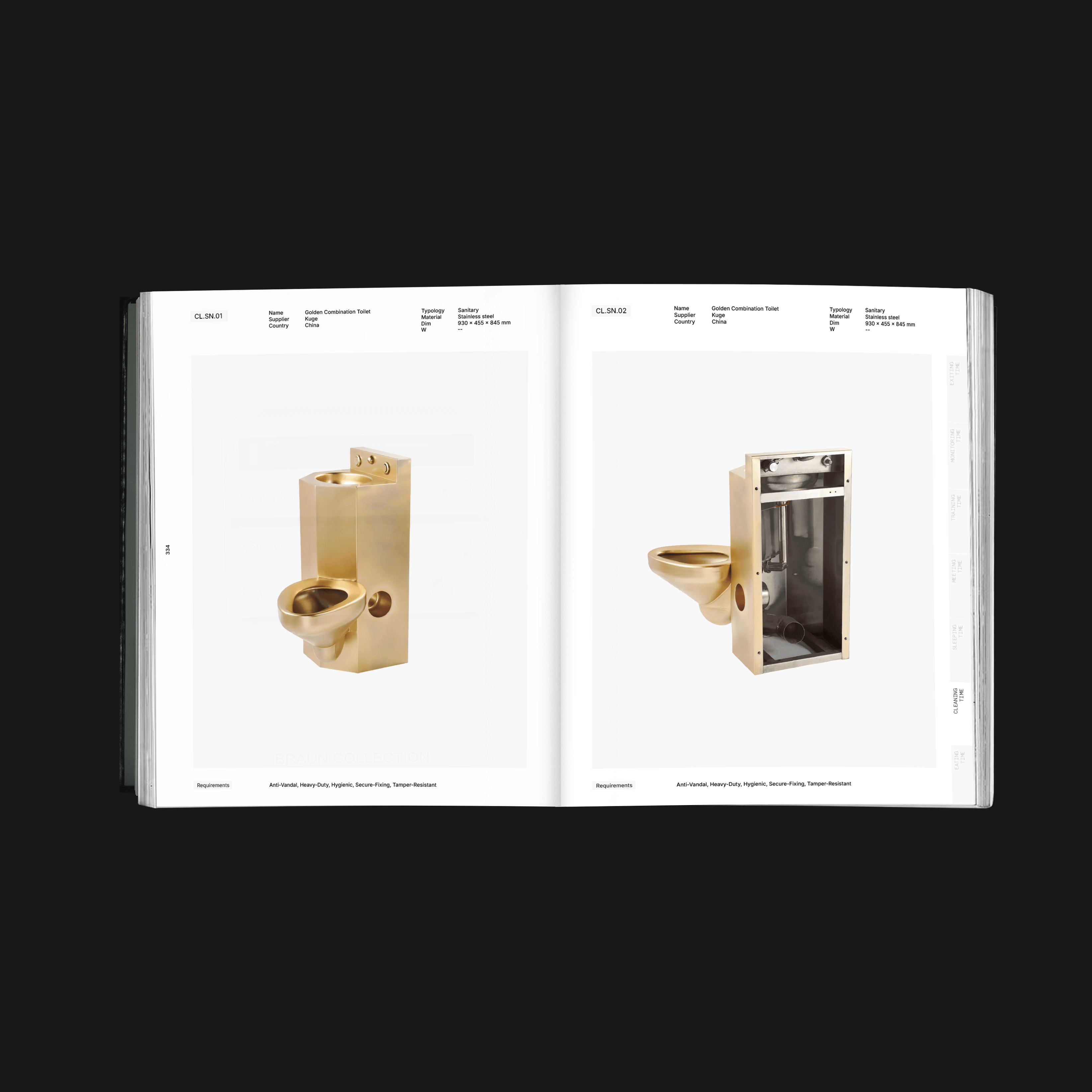

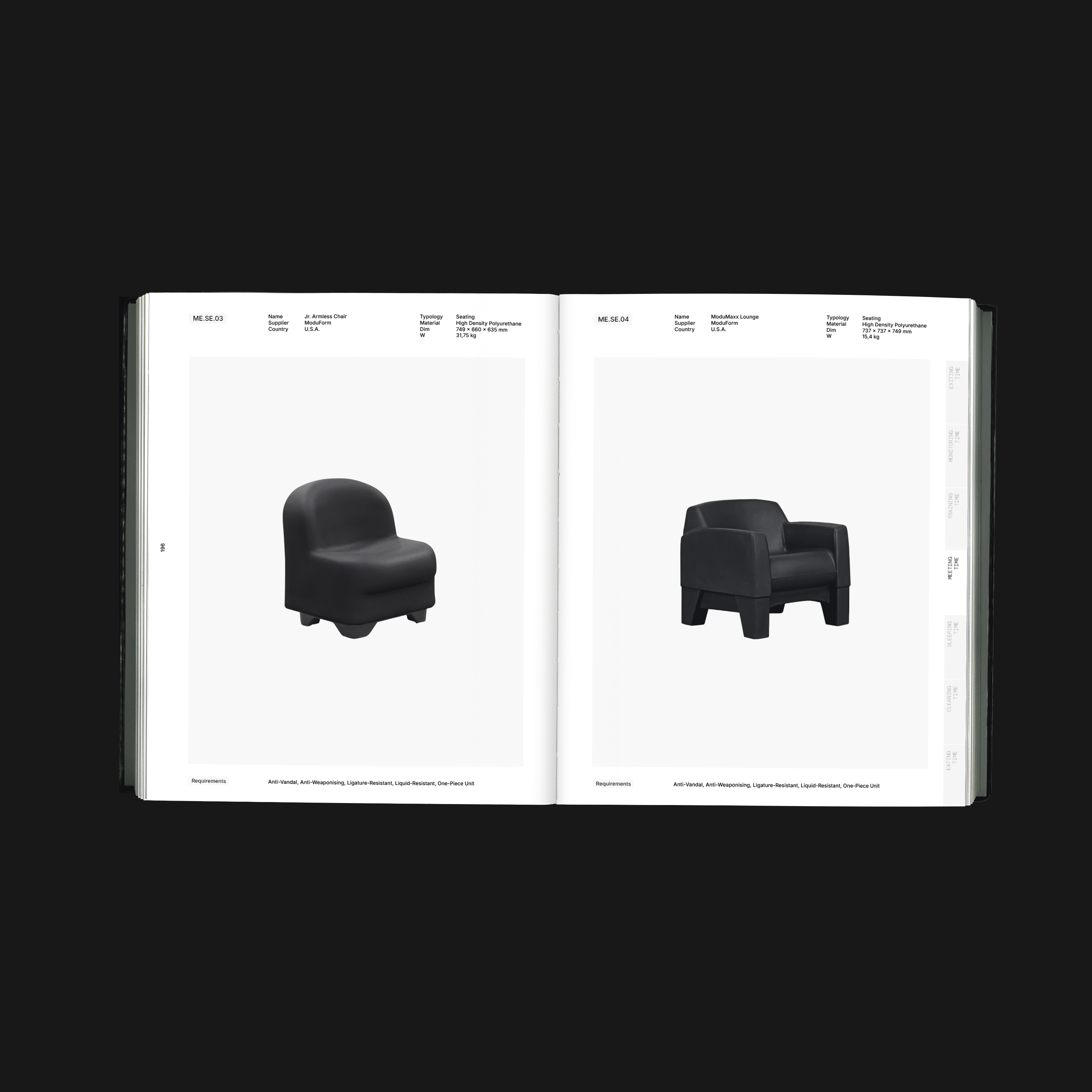

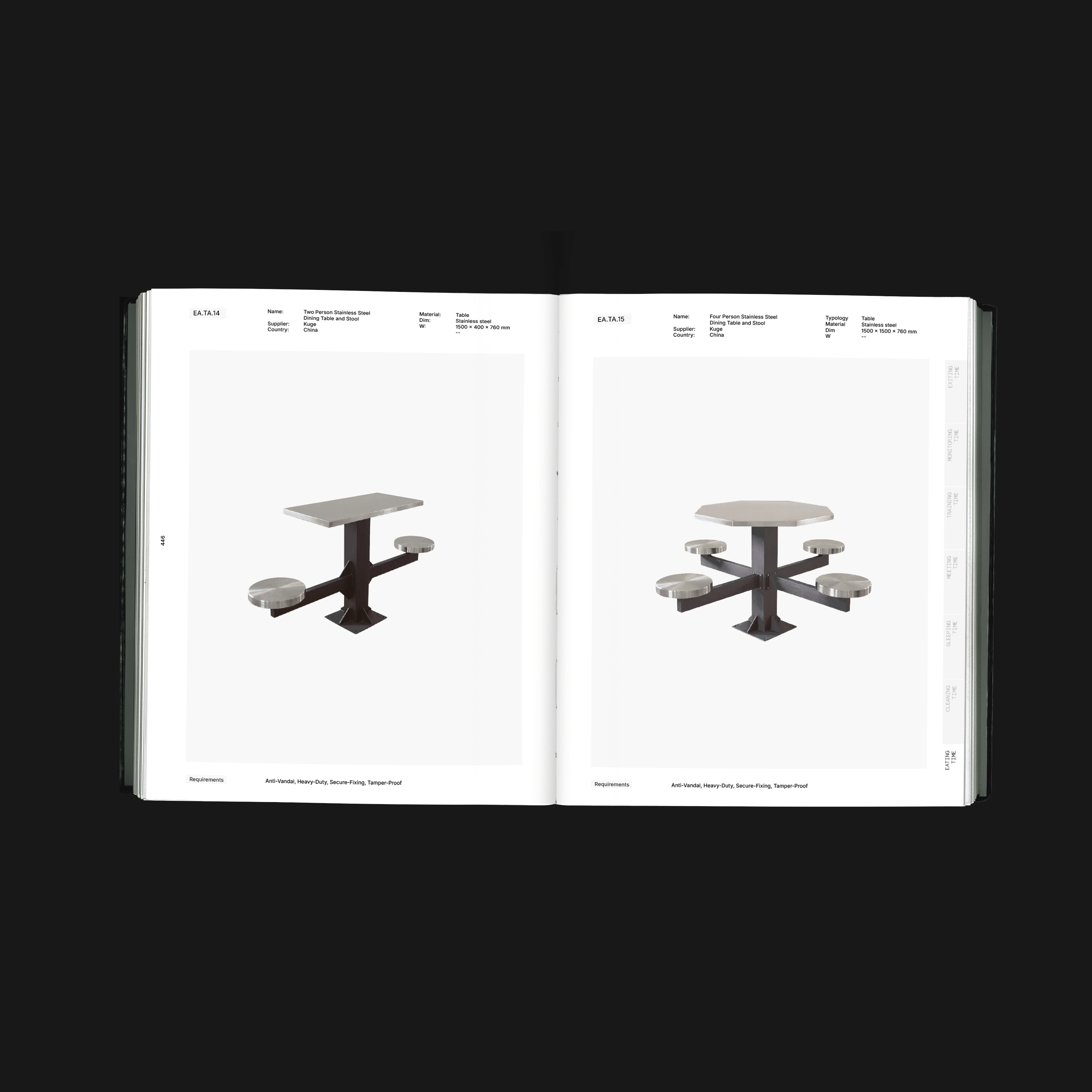

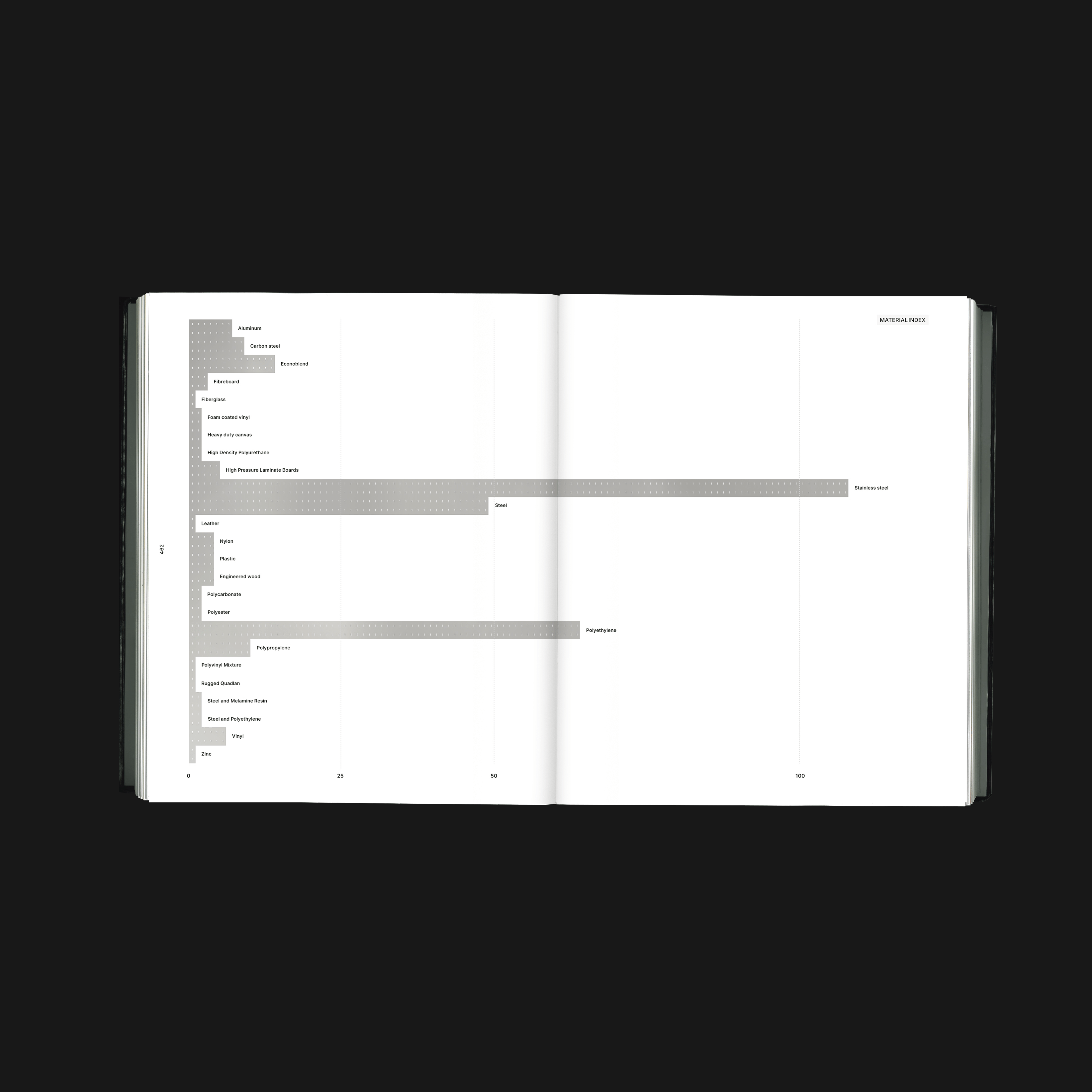

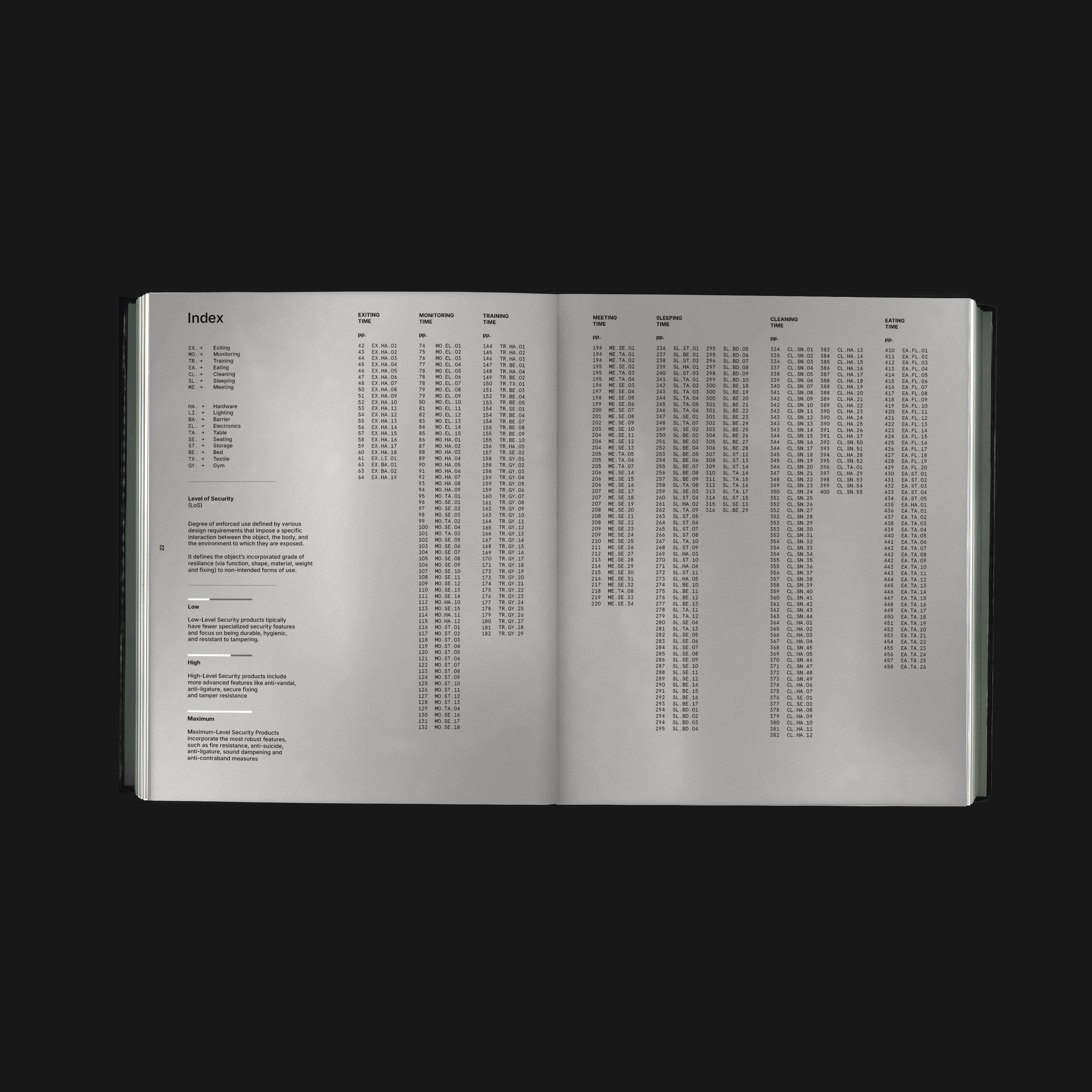

The exhibition features a selection of around 200 objects sourced directly from companies specialized in the design and production of prison furniture. These are items that, with varying degrees of deterrence, help define the perception of time and lifestyle within prison environments. One particularly compelling aspect of the exhibition is how it illustrates that the context and conditions in which these elements are introduced reveal how design becomes standardized and shaped according to national regulations, each responding to distinct security needs.

The exhibition layout is divided into five sections, each delving into key themes: Sleeping Time, Cleaning Time, Monitoring Time, Eating Time, and Entering Time. This breakdown is particularly interesting as it shows how all aspects of daily life within a prison are scheduled and confined within tightly controlled spaces and time slots.

Prison Times is the result of an extensive research process led by Giada Zuan, developed in collaboration with Kostantinos Venis, Luca de Carvalho, and Grazia Tonoletti, with graphic design by Andrea Cavallo. A team of designers under 30 managed to curate, coordinate, and produce an exhibition covering over 1,500 square meters, a 600-page editorial project, and a conference series aimed at encouraging reflection on one of the most pressing issues of our time.

I found it to be a particularly compelling exhibition because it offered a completely different—and more authentic—approach to exploring the design and architecture of these spaces and the elements that constitute them.

Exhibitions like this help draw attention to dire situations that affect all our communities. People often mistakenly believe that art and culture must provide answers—but few realize that their real purpose is to provoke questions and reflection among the public. The prison crisis is an issue that inevitably impacts our own lives as well. Today, prisons are overcrowded spaces where living and personal areas are sacrificed, in order to supervise and punish an ever-increasing number of people. The few institutions that still manage to carry out rehabilitative work now face budget cuts and outdated tools. Politics should take these issues seriously and abandon stadium chants or social media slogans—simplistic and aggressive messages that do nothing but fan the flames of an already raging fire.

Cover image: Prison Times: Spatial Dynamics of Penal Environments, Dropcity Milan, photography by Piercarlo Quecchia (DSL studio)

Alessio Vigni, born in 1994. He designs, edits, writes and deals with contemporary art and culture.

He collaborates with important museums, art fairs and artistic organisations. As an independent curator, he works mainly with emerging artists. He recently curated “Warm waters” (Rome, 2025), “SNITCH Vol.2” (Verona, 2024) and the exhibition “Empathic Dialogues” (Milan, 2024). His curatorial practice explores the relationship between the human body and the social relationships of contemporary man.

He writes for several specialised magazines and is author of art catalogues and podcasts. For Psicografici Editore he is co-author of SNITCH. Dentro la trappola (Rome, 2023). Since 2024 he has been a member of the Advisory Board of (un)fair.