When Diagnosis Is Told by Art

The Story of the Doctor-Patient Relationship

In the previous article with Spaghetti Boost, we explored an umbrella term: humanization of care. We often focused on the value that design, architecture, and culture can have in care environments. However, humanizing care also involves aspects such as communication and empathy, which healthcare professionals can and must offer to their patients. This approach not only makes patients more aware but also helps them reduce negative emotions.

Today, the patient-doctor or doctor-patient relationship is frequently discussed as the core of healthcare—a dynamic interaction that combines clinical expertise with relational skills. This relationship has undoubtedly evolved over time, reflecting the sociocultural changes of each era and shifting from a paternalistic model to one of mutual collaboration. Empathy, communication, and respect for the patient's personal history are fundamental to truly patient-centered medicine. This paradigm shift stems from the debate sparked by George Engel’s studies, which moved the focus from treating symptoms in a single organ to viewing the person as a whole, a synthesis of mind and body, emotions, and physiological data1. This holistic understanding transforms the patient from a mere clinical case, a bed number, or a pathology into a person. Narrative medicine becomes the primary methodology: an approach that values the patient's account of their illness experience. It goes beyond analyzing symptoms, considering personal lived experience as a key factor for a more accurate diagnosis and more effective therapy. This method aims to build a relationship based on mutual trust between caregiver and patient, empathetic listening, and an understanding of the human dimension of care. It turns the patient from a passive object into an active protagonist of their therapeutic journey.

An illustrative example of this concept is the TV series Doc – Nelle tue mani, inspired by the true story of Dr. Pierdante Piccioni. The series follows Andrea Fanti, a brilliant head physician who, after losing his memory due to a brain injury, must rebuild not only his medical skills but also his relationship with his patients. Through clinical cases and human stories, the plot explores the value of empathy and listening in medical practice.In Season 3, Episode 1 (Risvegli), Dr. Fanti notices a bruise on the back of a young patient. Through attentive dialogue, he uncovers a crucial detail: the boy had undergone acupuncture in unprofessional conditions. This information leads to the diagnosis of a severe complication caused by a needle fragment left in the body, which triggered a dangerous infection. This scene highlights how gathering the patient’s personal history can be pivotal in understanding an illness, demonstrating the importance of integrating empathetic listening with clinical expertise to provide more humane and effective care.

Frame of Risvegli, I episode III season, Doc-Nelle tue Mani, 2024

Frame of Risvegli, I episode III season, Doc-Nelle tue Mani, 2024

In the history of medicine, these concepts are not new but have evolved over time. The aim of this article is to trace how, throughout history, the doctor-patient relationship has been represented and reinterpreted in visual culture. Through a visual and chronological journey, we will explore how depictions of illness, doctors, and patients reflect cultural, social, and ethical changes in the perception of medicine. This highlights how art serves as a powerful mirror of the times, capable of illustrating not only medical advancements but also the evolving nature of human relationships and sensitivities toward suffering and care.

Antiquity: Medicine as a Religious and Symbolic Practice

In antiquity, the physician was seen as an intermediary between the human and divine realms. In Egypt, medical papyri, such as the famous Ebers Papyrus, combined therapeutic practices with prayers to the gods. In Greece, figures like Hippocrates marked the transition to a more rational approach, yet the doctor-patient relationship remained highly hierarchical. In Roman art, mosaics and statues depicted Asclepius, the god of medicine, symbolizing healing as a divine gift accessible only through the power and wisdom of the healer-physician.

Middle Ages: Suffering, Faith, and Medicine

During the Middle Ages, the connection between faith, illness, and healing persisted. Physicians, often monks, operated within a framework where suffering was seen as part of the divine plan. Depictions of the Black Death, such as manuscript miniatures, reveal scenes of despair and helplessness, with the physician portrayed as an austere or distant figure, shielded by masks and religious symbols. Medieval medicine placed the act of healing more in the realm of spirituality than in that of science.

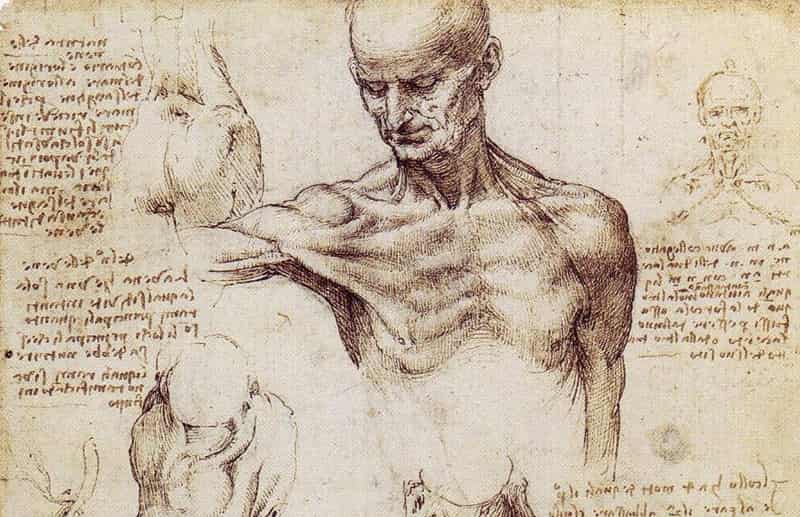

Renaissance: scientific progress and the centrality of the patient

The Renaissance marks a turning point: there is a new understanding of the human body and medicine. Brilliant artists such as Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo exalt anatomical study, transforming the human body into a subject of investigation and artistic representation. Leonardo’s anatomical drawings, based on dissections, not only increase medical knowledge but place the patient at the center of attention, though as an object of study rather than an individual with a personal history. This period represents the beginning of medical modernity, with a tension between scientific advancement and empathy toward the sick.

Modern Age: medical science at the center of the scene

With the Enlightenment, medicine definitively emancipates itself from religion, establishing itself as an autonomous discipline. The painting of the era, such as The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp by Rembrandt (1632), reflects this very transformation: the physician is depicted as a scholar at the center of the scene, while the patient, represented by the inert body on the table, assumes a passive role. This period consolidates the medical model as a figure of authority.

Realism and the Industrial Revolution: hospitals and collective illnesses

With the Industrial Revolution, the role of the collective takes on greater significance, and this extends to medicine as well. Works by Jozef Israëls depict hospitals and care settings, highlighting the difficult working conditions of doctors and the suffering of patients. Attention increases on lung diseases and injuries resulting from industrial accidents.

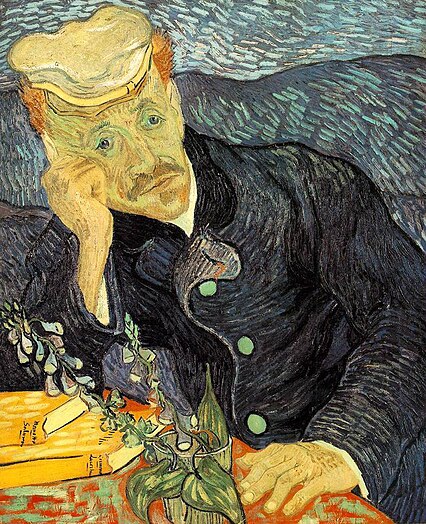

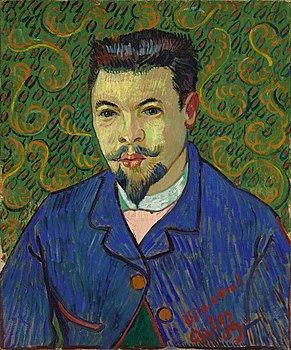

Impressionism: the personal relationship between doctor and patient

With Impressionism, another shift begins: the doctor-patient relationship becomes more human. Vincent van Gogh, in the famous portrait of Dr. Paul Gachet, depicts his attending physician with a melancholic expression, symbolizing emotional fragility and the bond between the two. Similarly, the portrait of Dr. Félix Rey reflects a more intimate and respectful relationship between doctor and patient, breaking with the hierarchical view of the past.

Expressionism and criticism of medical technology

Expressionism brings the psychological dimension of illness and doctor-patient communication to the forefront. Artists like Edvard Munch explored alienation and suffering, questioning the growing reliance on medical technology. The art of this period already reflects a tension between the effectiveness of cures through technology and the need to maintain a close connection with the patient.

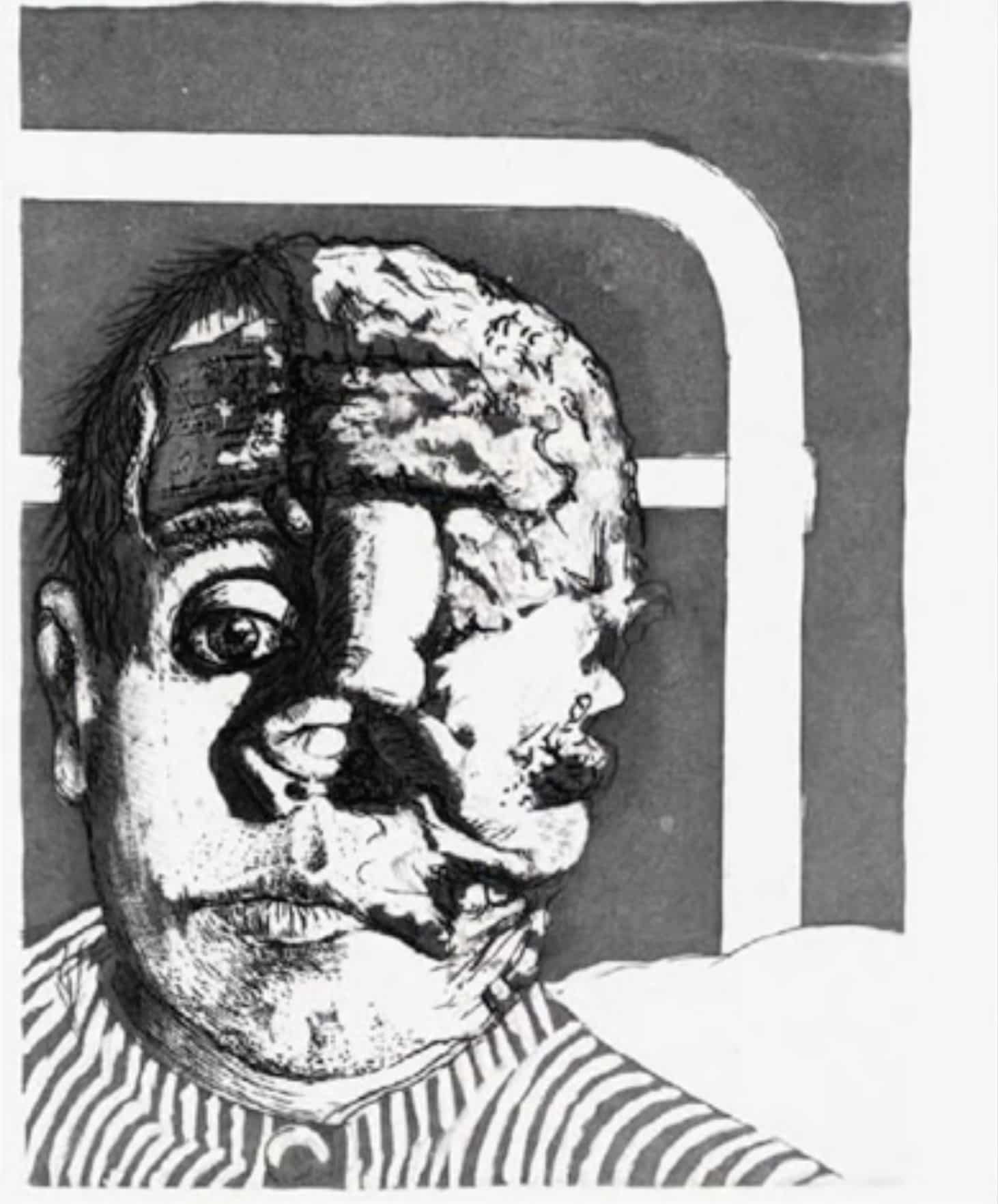

Art Between the Wars: psychology, post-traumatic trauma, and mental health

Between the two world wars, art fosters growing awareness of the psychological sphere and trauma. The scars left by the First World War are well represented by artists like Otto Dix and George Grosz, both veterans of the conflict. They depict the mutilated and wounded, highlighting the difficulty of traditional medicine in addressing psychological traumas. Their works criticize society’s inability to deal with invisible wounds, leading to a growing awareness of the importance of psychiatry. Furthermore, during the Great Depression, Dorothea Lange’s photography reveals social and emotional suffering, demonstrating how illness was also a psychological experience. These artistic changes reflect the evolution of medicine toward a more holistic vision, encompassing not only physical treatment but also mental well-being.

Second World War: Trauma and Psychiatric Medicine

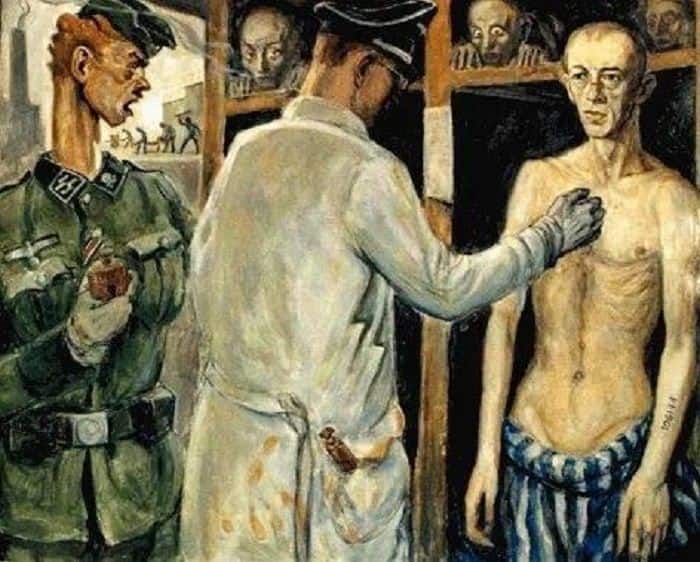

During and after the Second World War, art and medicine continued to focus on psychological trauma. The devastating experiences of soldiers and civilians became subjects of medical and psychiatric study. Artists like Francis Bacon and David Olère depicted physical and psychological disintegration, expressing the pain and suffering caused by the conflict. In medicine, psychiatric hospitals emerged as a response to the enormous demand for treatment of the invisible wounds of war.

Contemporary Art: Medical Ethics and Digital Medicine

At the end of this journey, attention turns to the contemporary landscape. Art explores themes of biotechnology, global health, and representations of the doctor-patient relationship in the digital age. Installations like Body Worlds by Gunther von Hagens question the boundary between science and spectacle, while works inspired by the pandemic, such as murals dedicated to hero doctors, celebrate their essential role. At the same time, the challenges of telemedicine are addressed, highlighting patient loneliness and the physical distance technology can create. An emblematic example is Carolyn Lazard's photographic project Sick Time, Sleepy Time, Crip Time, which explores the experiences of chronic patients.

Body Worlds, Gunther von Hagens, 2011

Body Worlds, Gunther von Hagens, 2011

Today, the doctor-patient relationship often suffers from significant communication gaps, as highlighted in the book Ho vinto una biopsia by Minnie Luongo. The author, an expert journalist in the medical field, explores how interactions between doctors and patients are sometimes marked by a lack of empathy, inadequate listening, and insufficient explanations. Luongo emphasizes how these deficiencies can exacerbate the emotional distress of patients, already fragile due to illness. A striking example involves the difficulty of receiving clear and personalized information about one’s treatment plan, often conveyed in a mechanical and impersonal way. This technical and distant approach not only undermines the patient’s trust but also increases fears and uncertainties, making the healthcare experience more traumatic, especially when encounters with doctors become rarer.In response, the author offers practical suggestions to improve communication, including informational materials that help patients face difficult conversations with doctors, proposing useful questions to gain clarity. The book is not only a critical testimony but also a practical guide to raising awareness among healthcare professionals about the importance of a human, empathetic, and respectful relationship with patients, promoting a form of medicine that not only cures but also listens.

"Mr. Simpatia received me standing: as I approached the X-rays, he silenced me with, 'Madam, it’s useless. You wouldn’t understand anything.' I replied that I understood something, but he preempted me, declaring, 'There’s a cluster of microcalcifications. Well, we’ll have to operate and do some radiotherapy2.'”

In conclusion, we may ask: what can be done concretely to improve the doctor-patient relationship and facilitate the healing process? Two practical and effective proposals emerge to raise societal awareness and train new doctors.

Patient education is a fundamental tool for improving patients' understanding of the treatment process. Educating patients makes them more aware of their conditions and therapeutic options, facilitating fruitful dialogue with doctors. An example of awareness-raising is the #KnowYourLemons campaign by the eponymous foundation, which in 2019 created an image of twelve lemons in an egg carton to illustrate the signs of breast cancer. This visual, friendly, and easily understandable approach taught men and women to recognize the twelve most common symptoms of this disease, breaking the taboo and fear surrounding it. The simplicity and accessibility of the image, shared on social media, allowed many people to quickly and empathetically educate themselves without facing overly complex or distressing representations of the illness.

#KnowYourLemons, Social Campaign, Know your lemons Foundation, 2019

#KnowYourLemons, Social Campaign, Know your lemons Foundation, 2019

Another proposal on the educational front involves the application of the visual thinking strategy (VTS), which uses the analysis of works of art to refine doctors’ observation and listening skills. Studies conducted by institutions such as Harvard Medical School have shown that detailed observation of paintings helps doctors develop a sharper and more empathetic perspective, improving their diagnostic ability and approach to patients. This exercise not only enriches clinical skills but also promotes greater attention to non-verbal details, which is essential in the doctor-patient communication process.

As seen, medicine is not only science but also storytelling, listening, and humanity. Rediscovering empathy in the doctor-patient relationship, as taught by art and innovative projects, means restoring dignity and trust to those facing fragility. The future of care lies here: treating people, not just symptoms, both in patients and healthcare providers. It is about the well-being of the community.

Sources:

1E. Grossi (2013), Cultura e salute. La partecipazione culturale come strumento per un nuovo welfare. Milano, p. 1-42.

2L. Minnie. Ho vinto una Biopsia, Emmebi Edizioni Firenze, 2022.

Bibliography for further reading

- Cartwright L., Screening the Body: Tracing Medicine’s Visual Culture, University of Minnesota Press (1995)

- Domenici R., Arte e Medicina: Il medico, il paziente e la malattia, Aonia Edizioni (2023)

- Gilman S. L., Health and Illness: Images of Difference, Reaktion Books (2004)

- Kemp M., Visualization: The Nature Book of Art and Science, University of California Press (2000)

Cover image: The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp by Rembrandt, 1632

She is a cultural designer and doctoral candidate in Medical Humanities and Welfare Polices. Her common thread is caring for people's wellbeing, whether it is behind a stage with Grato Cuore, Rosetum Jazzfestival, a professorship at the Mohole School or research to rethink the design of healthcare environments through artistic interventions. With Spaghetti Boost he will address various topics on the combination of art and sanctity in international and national contexts, proposing how to concretely innovate it.