Tracey Emin at Palazzo Strozzi

“A lot of people think art is frivolous,” says Tracey Emin, the eminent artist who withstood years of accusations of frivolity herself. No one would level such an insult anymore at a woman whose fiercely confessional body of work has carved out space for autobiography and a woman’s life to reflect the human experience, for the power of the creative act especially against the evil rumblings of our times.

Her silver-streaked hair pulled back, her face defiant, Emin continues her speech: “Art has never been more important than now. When the cavemen and cavewomen were painting on their walls, they were not clubbing each other to death. If we understood as humankind what we can create that is beautiful, that resonates with spirituality, that resonates with love, that resonates with understanding of our own mental and physical and emotional being, then we probably wouldn’t attack and wish to kill each other.”

Tracey Emin, Sex and Solitude, Palazzo Strozzi, Firenze, 2025. Photo Ela Bialkowska, OKNO Studio © Tracey Emin. All rights reserved, DACS 2025

Tracey Emin, Sex and Solitude, Palazzo Strozzi, Firenze, 2025. Photo Ela Bialkowska, OKNO Studio © Tracey Emin. All rights reserved, DACS 2025

A room’s crowd holds its breath, leaning in to hear her every word. “Art is not a picture. Art is not a decoration. Art is something which transcends all of that,” Emin says. “Art will make a difference.”

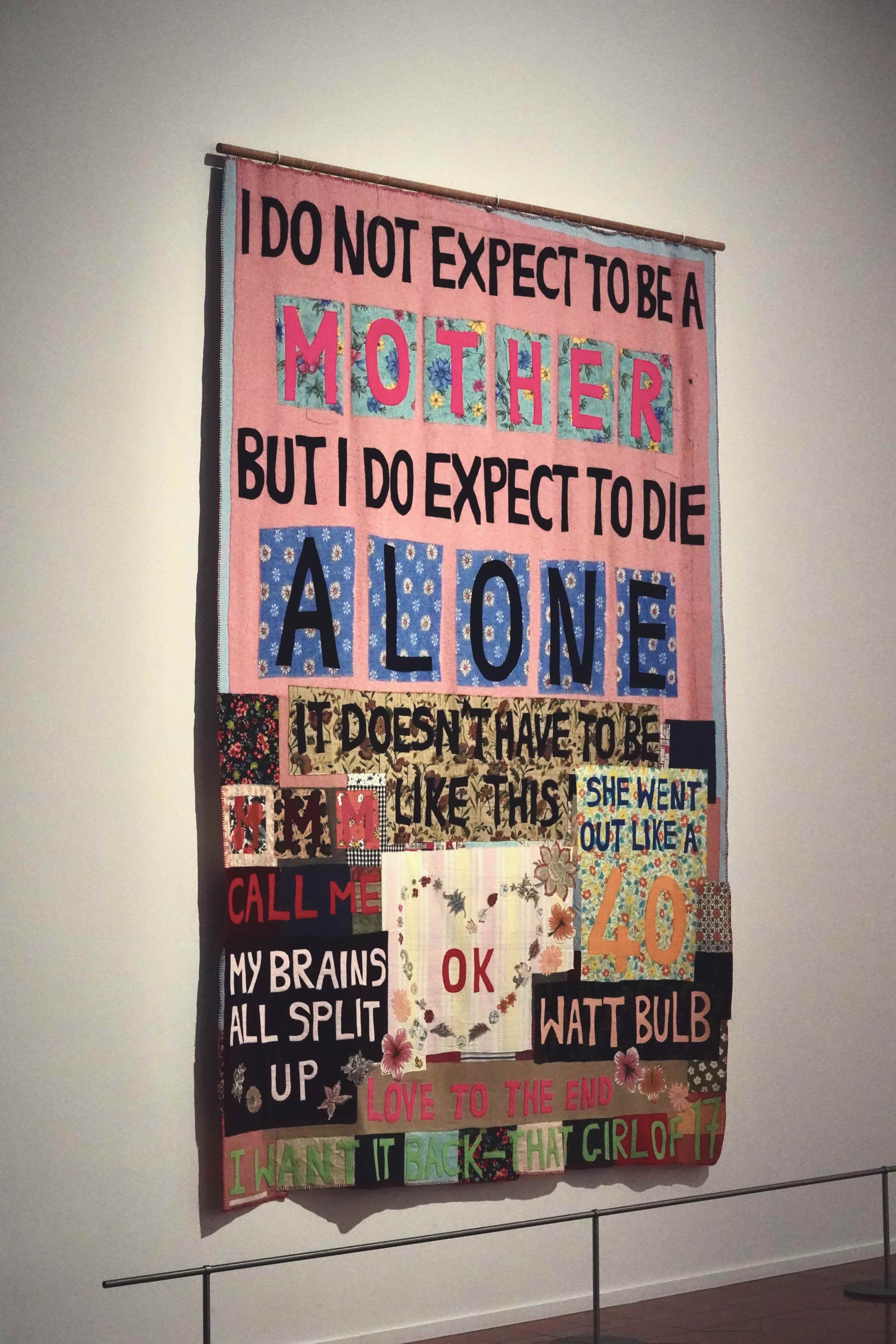

We are gathered on an upper floor of Palazzo Strozzi, a 16th-century noble residence turned museum in the heart of Florence. Emin has arrived more than an hour late, her health interfering with her timing, but the room is still packed shoulder-to-shoulder for her, as she inaugurates her largest show ever in Italy. The galleries feature over sixty career-spanning works — her raw paintings, shaped-by-hand sculptures, declaration-embroidered quilts, and her handwritten poems rendered in glowing neon. “Sex and Solitude” — the title of Emin’s exhibition — is scrawled as a blue neon sign, and hangs across the sandstone exterior of the museum, a message sure to shock the primmer denizens of Florence’s medieval center.

Shock has never stifled Emin. The artist, who grew up in working-class Margate and dropped out of school at 13, roiled the scene as part of a generation-defining 1997 Sensation show in London of the YBAs — the Young British Artists cohort that included Sarah Lucas, Damien Hirst, Rachel Whiteread, Chris Ofili, and others. Their art differed greatly in style, but was by and large confrontational — none in a more unfiltered and almost painfully revealing way than the work of Emin. Her contribution instantly became notorious: Everyone I Have Ever Slept With, a tent appliquéd inside with those names — not just lovers but also friends, family members, her two unborn children, her abusers — scandalized the public, as if someone, a woman no less, were bragging about notches on a bedpost as art.

I saw the tent when it went on view in New York. Peering in, I dismissively expected little, after hearing so much criticism of this supposedly brash bit of personal exposé. Yet the forthrightness of it pulled me into the story Emin was telling of intimacy, sex, and trauma, and widened to my own, and to all of our stories of what we experience in the inmost and sometimes wrenching, sometimes lonely parts of our lives. This is the unvarnished personal candor that Emin has shared with us her entire career — a vast mirror to the jagged contours of our own existences.

At Palazzo Strozzi, sex is everywhere, as the show’s title promises, along with the aching feeling of solitude. In the archway-lined courtyard of the museum, and visible to anyone passing by on the street, a seven-meter colossus of a sculpture depicts a woman’s body bent over on all fours, her bronze shape roughly formed but her physical position unmistakably primed for penetration, and perhaps hoping forlornly for love.

Upstairs in the galleries, the walls are lines with large paintings in Emin’s spontaneous brushwork, which depict the arched bodies of couples entwined in sexual communion yet emanating anguish — fluids spurting forth more like blood from a wound than the exstasy of release.

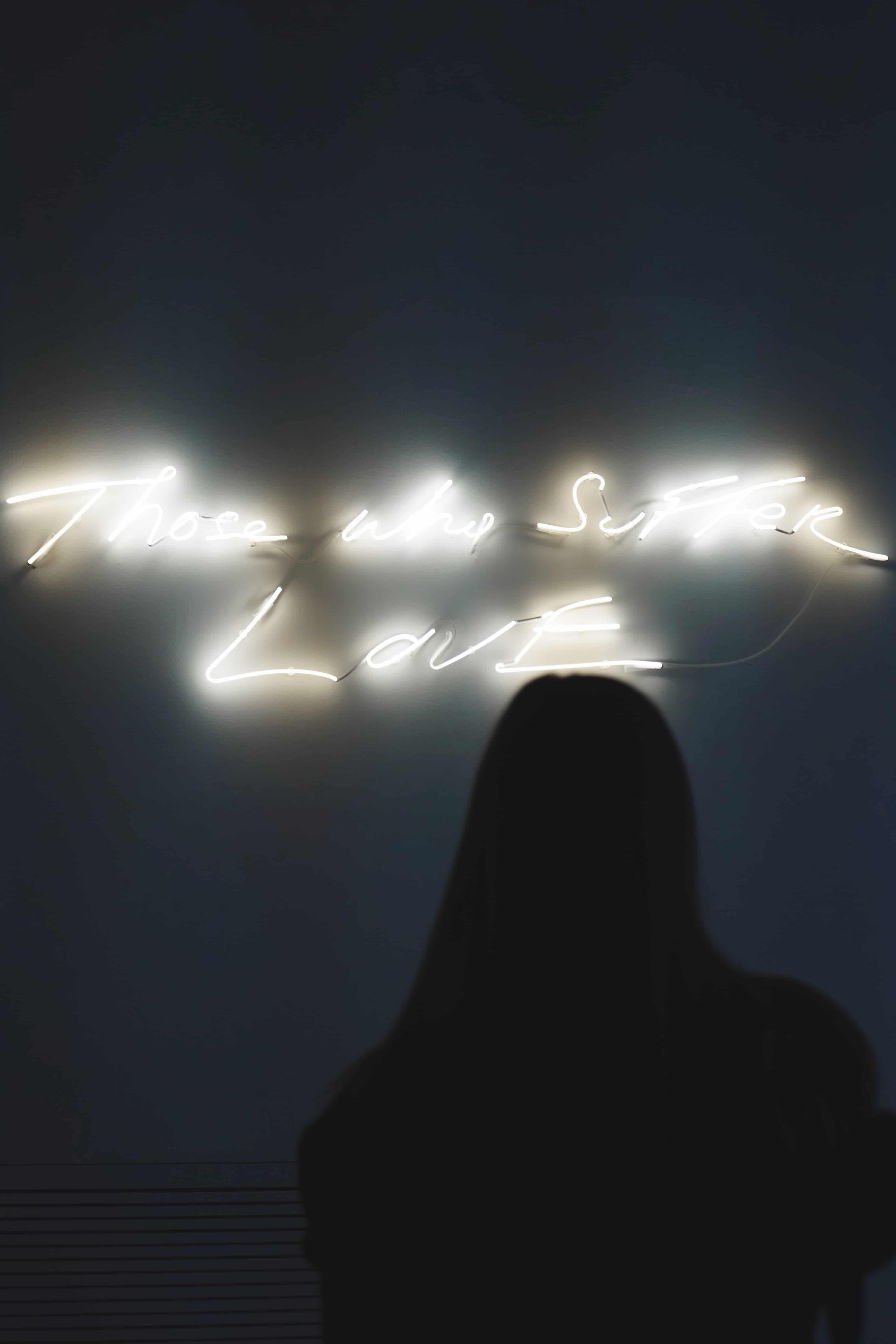

The artist’s aphorisms and poems in neon put words to the emotional longing, illuminating the galleries with their haunting and desperate desires, like the pink-lit words of I Longed for You from 2019 that hang on a wall at the exhibition:

I longed for you – I wanted you

The only place you came to me was in my sleep

Too far for me to touch

With time you slowly disappear

Tracey Emin, Sex and Solitude, Palazzo Strozzi, Firenze. Photo by Laura Rysman.

Tracey Emin, Sex and Solitude, Palazzo Strozzi, Firenze. Photo by Laura Rysman.

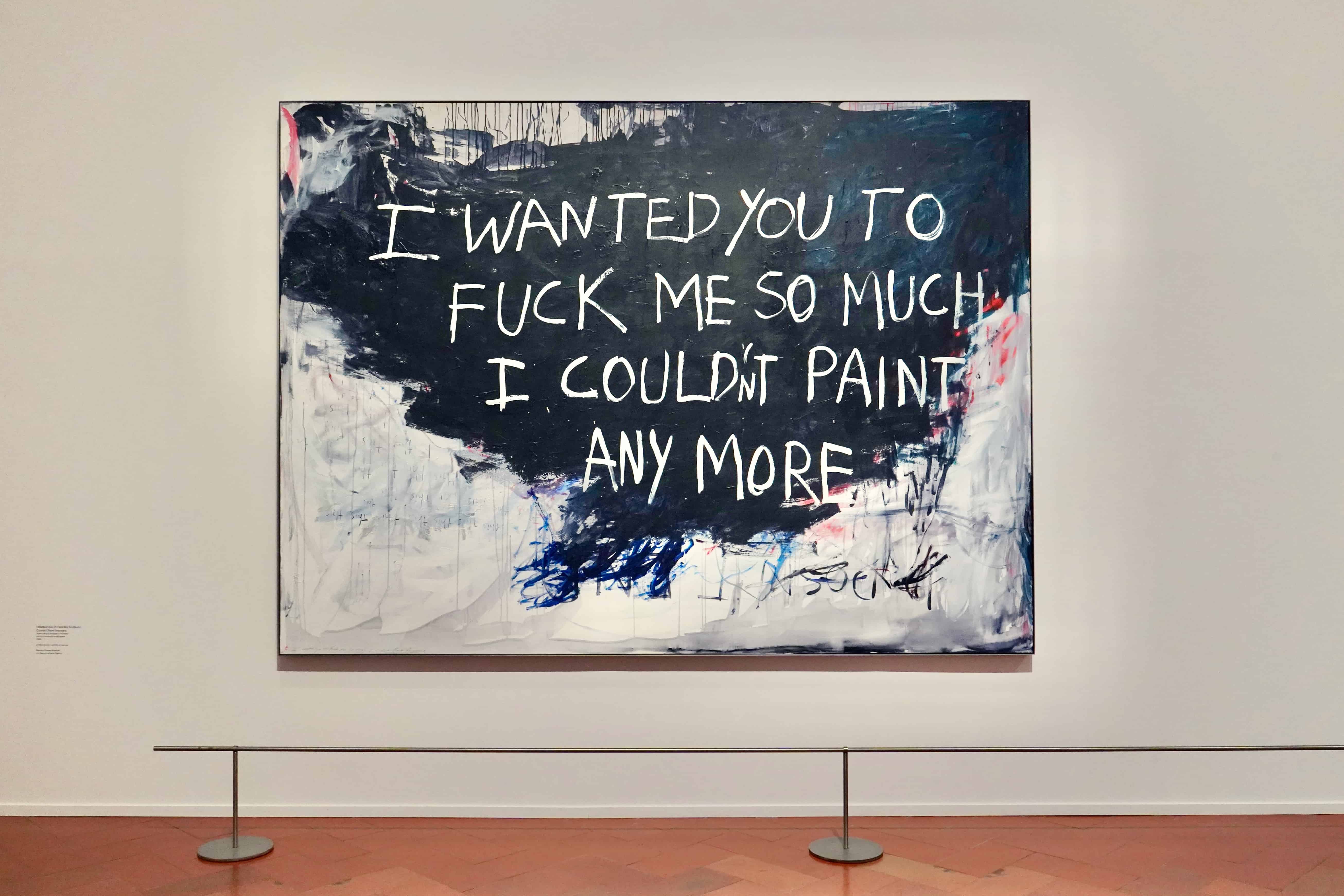

“People thought my work was just about sex, and about being salacious and shocking, but it never has been,” says Emin. The female body has been portrayed by male artists as a vessel of desire since the dawn of human expression, but for Emin, as with female artists in general, frank revelations about the female body and desire were discounted as diaristic. They were never understood to have a universal resonance until recently. “It’s only now that people have started to see properly what my work is about,” she says. Sex and solitude. Love and suffering. Aggression and victimhood. Life and the specter of dying.

Today, Emin’s esteem is incontestable. Her most controversial work, the 1998 Turner prize-nominated My Bed, is a mattress surrounded by the detritus of her own emotional upheaval — filthy sheets, used condoms, bloodied underwear, emptied liquor bottles — but it now shares a gallery with Francis Bacon as part of the collection at the Tate.

A member of the Royal Academy of Arts, she’s only the second woman ever appointed to the institution, whose history stretches all the way back to 1768, which says as much about the sexism of the Academy as Emin’s supreme recognition. And though previously the spiky enfant terrible of the art world, Emin was made a Dame Commander by the king in 2024 for her services to the arts — an honor all the more poignant because Dame Tracey expected she would die years before that.

In the spring of 2020, Emin was diagnosed with an aggressive bladder cancer, a disease with a frighteningly low rate of survival. She underwent surgery that removed her lymph nodes, her uterus, and part of her urinary tract, bladder, vagina, and bowel. “I accepted the dying,” she says now. Ever fearless, he told herself “to start looking after life — to look after living every moment.”

Now 61 and miraculously in remission, “My reward for being here is to do the right thing,” she says, giving a sardonic smile. In 2023, Emin launched an artist’s residency, a rent-free studio for art students, and a free art school program, all in her hometown of Margate.

After her cancer surgery, she couldn’t paint for an entire year, couldn’t even lift a teapot, as she tells it, but after her long recovery, “I got back in the studio and painted like a dervish, like a banshee, like someone insane and crazy.” The nearness of death clarified life into pure imperatives: making art, and aiding others to make art.

Restored to her studio again, her whole body felt liberated in the physical and creative act of art. “Painting to me,” she says, “was complete freedom.”

Cover Image: Tracey Emin, Sex and Solitude, Palazzo Strozzi, Firenze, 2025. Photo Ela Bialkowska, OKNO Studio © Tracey Emin. All rights reserved, DACS 2025

Laura Rysman is a regular contributor to The New York Times, as well as the Central Italy correspondent for Monocle, and a contributing editor to its sister magazine, Konfekt. An American journalist and a longtime resident of Italy, she writes about the country's art, fashion, and travel scene, with a particular focus on the creativity, craft, and culture of Italy.