Zdzisław Beksiński: Life, Art, and Tragedies of the Polish Painter of Horror

From childhood in Poland to worldwide success, and ultimately a tragic end: the artistic and personal journey of one of the most enigmatic painters of the twentieth century.

It seemed like any other morning that day in 1970, in Krakow. A car was heading toward the city’s Academy of Fine Arts. Traffic flowed smoothly. The car followed the long curve, and in the distance, an unguarded railway crossing came into view. The barriers were raised. The vegetation around was so dense that it was impossible to see what lay on either side. At the wheel was Zdzisław Beksiński, a young painter who had been enjoying considerable success in Poland for several years. Some of the leading newspapers had started writing about him. From the car’s speakers, muffled by a light background hum, flowed the sweet notes of Chopin’s Sonata No. 2.

The car approached the tracks. The wheels met the rails. From the right, a shadow fell across the vehicle. A fraction of a second—there wasn’t even the dull sound of impact. Only darkness and silence.

And is this the end?

No, a darkness that would last for three months.

After the accident, Zdzisław Beksiński would awaken in a hospital bed, having been in a coma for around ninety days. That darkness might have seemed like the end, but many consider it the true beginning of Beksiński’s painting career and his rise to success. It was undoubtedly an event that would change his life, transforming him entirely.

After his awakening, he would say: “I have seen hell, and in order not to go insane, I must now begin to depict it.”

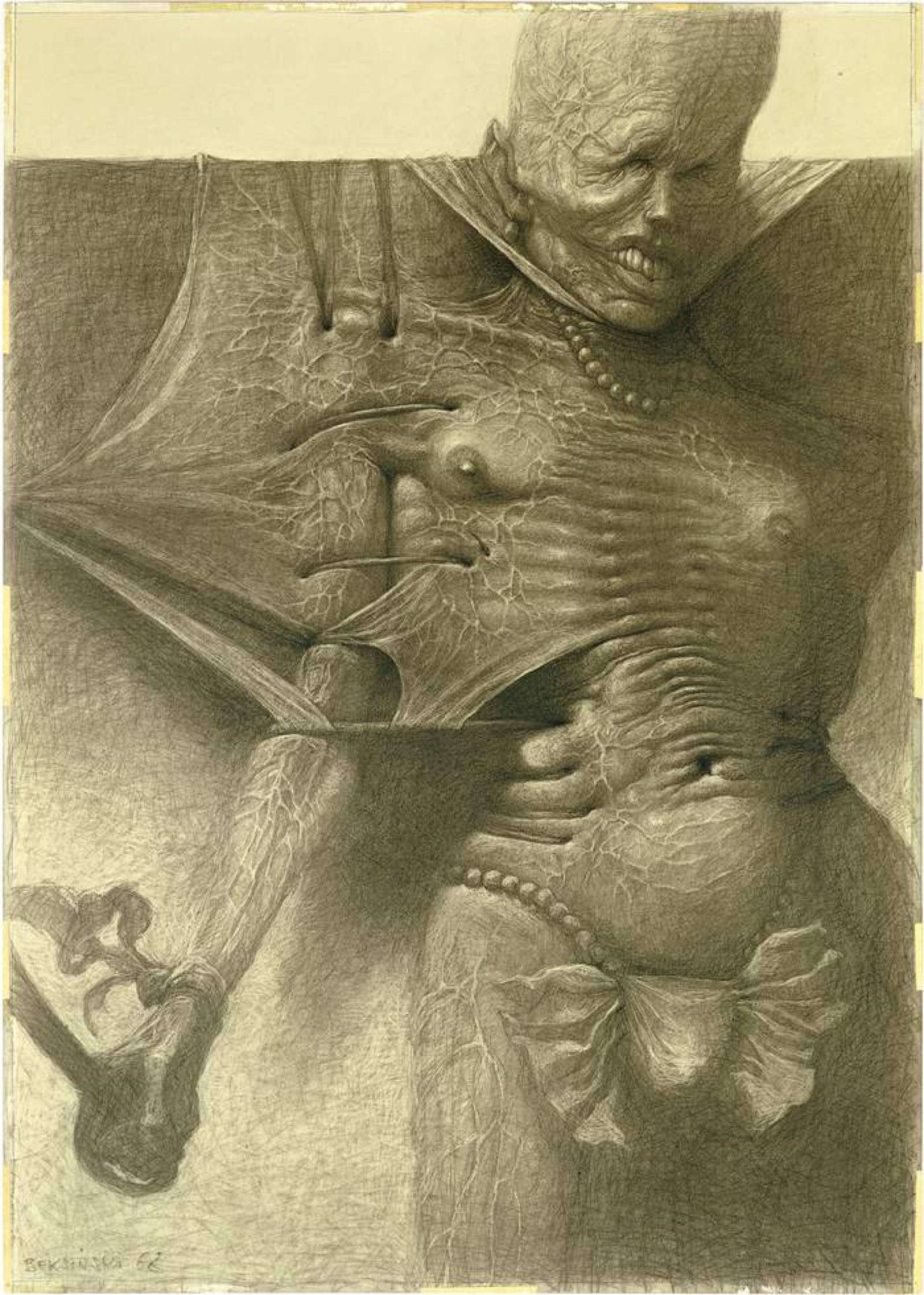

Zdzislaw Beksinski, Untitled drawing, 1968

Zdzislaw Beksinski, Untitled drawing, 1968

On February 24, 1929, in Sanok, a town in southern Poland, Zdzisław Beksiński was born. For his father, a prominent businessman, there were few alternatives: his son was expected to study economics in high school so that one day he could secure a stable job.

The problem was that these were tragic years for Europe, especially for Poland, which in 1939—when Beksiński was only ten years old—was occupied by the German Nazi army. His childhood and adolescence were profoundly marked by the shadows of war. Yet life had to go on. Beksiński, like many of his peers, graduated from a clandestine Polish high school that continued to hold lessons without the occupiers’ knowledge. In 1947, Poland was liberated, and the Polish people sought to regain a semblance of normality. Once again, Zdzisław had no say in his own future: his father forced him to enroll in the Faculty of Architecture in Krakow. Moving to the capital led him to meet Zofia Stankiewicz, the love of his life. It was love at first sight, which soon grew into something far more serious.

In 1951 they married. The following year, Beksiński graduated in Architecture, and in a country undergoing reconstruction, finding a job at a construction company was not difficult. But deadlines, strict schedules, responsibilities, and blueprints were not for him. He soon began to despise all of it and embarked on his journey toward photography. Meanwhile, he also changed jobs, becoming a bus designer for one of the country’s leading automotive factories.

In 1958, his passion for photography became something more concrete, especially after he met other Polish artists with whom he would form an informal group open to literary and philosophical discussions. Over the next two years, he participated in several exhibitions, but once again, he felt a growing dissatisfaction with what he was doing.

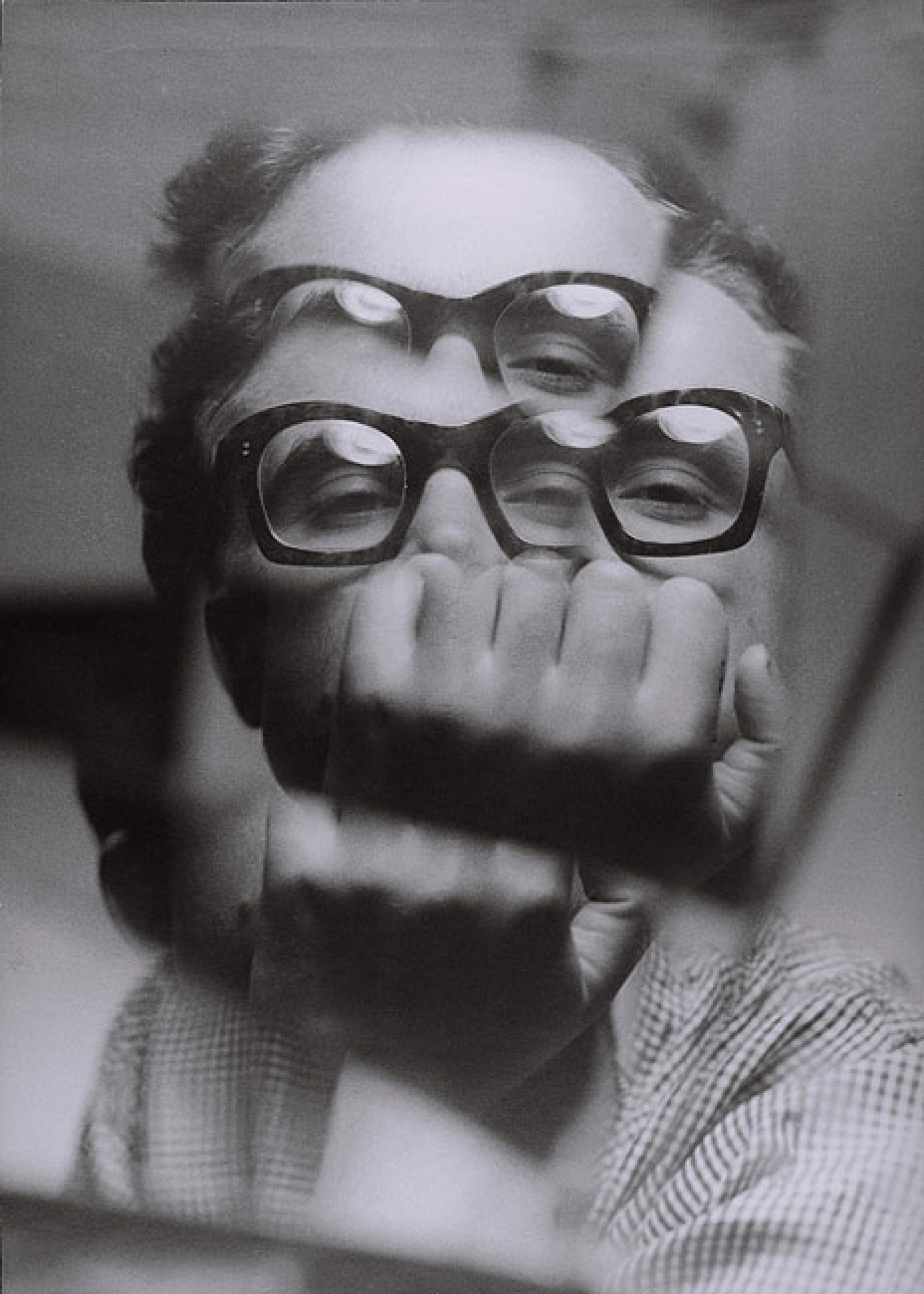

Zdzisław Beksiński, Autoportrait, 1956-57

Zdzisław Beksiński, Autoportrait, 1956-57

In 1960, he abandoned photography because he found it too limiting and turned his focus to drawing and painting.

"These forms of expression are fundamental for me because they allow me to photograph dreams," Beksiński replied when asked about the reason for this change.

His works began to circulate, and his success steadily grew. He was even offered a scholarship in New York by the then director of the Guggenheim Museum, but Beksiński chose to remain in Poland and pursue his career in his homeland. A decision that would prove wise: his success in his native country soon became firmly established.

By 1967, thanks to increasingly frequent sales, he was able to leave his job as a bus designer and dedicate himself entirely to his art. It was a happy period marked by financial stability.

Everything was going so well that it seemed almost too good to be true. But life is unpredictable. And so it came to that morning and that unguarded railroad crossing. The car was struck by the train’s violence. It crumpled on itself, and Beksiński suffered severe head trauma that plunged him into a deep coma, destined to last three months.

Many link this episode to a radical change in his artistic vision. Personally, I am not sure if that is entirely true. But based on the objective evidence of what he would create from that moment onward, it is impossible to deny that Beksiński’s early style became permeated by a dark world, populated by skeletons and demons.

Two years after that tragic accident, in 1972, Beksiński presented his new paintings in an exhibition in Warsaw. The public, familiar with his previous style, barely recognized him. Before their eyes were now only infernal scenes, unsettling landscapes inhabited by monstrous figures. These were visions that no other artist dared to represent, or perhaps could have translated onto canvas.

After that tragic incident, Beksiński was never the same. His art became his therapy, the only way to bring to light what devoured him from within. He was so reserved, so averse to the spotlight, and so immersed in his inner world that his paintings appeared almost too violent compared to the image others had of him.

Zdzisław Beksiński, Untitled, 1984

Zdzisław Beksiński, Untitled, 1984

Despite the slow erosion that those visions caused in Beksiński, his art continued to make waves. In 1975, the national art critics’ jury declared him the best artist of the first thirty years of the Polish People’s Republic, an honor that, however, did not reflect his actual financial situation. Shortly after that award, Beksiński was forced to leave his house in Sanok, the hometown he had returned to with such joy. In 1977, he moved to Warsaw with his wife and son. It was a difficult relocation: too many accumulated works, too many things to carry, and the decision to leave that house weighed heavily.

Beksiński did not hesitate: a group of paintings would never leave those walls. They were too personal, perhaps even unsatisfying according to his high standards. He decided to set them on fire, destroying them forever. No one has ever been able to reconstruct which works were lost.

When he spoke of the coma, he always remembered it as the darkest moment of his life. But he could not have imagined what awaited him at the end of the 1990s. His wife Zofia died of cancer in 1998: the woman who had always supported him, his faithful and beloved companion, was gone forever. Sadness enveloped the Beksiński household, a haze of melancholy seemed to have emerged from those canvases and filled the home. From that moment, his paintings became even more windows into his inner world.

Life, however, reserved yet another shock, and another tragedy struck just a year later. On Christmas Eve, his son Tomasz took his own life at the age of 41. No letter, no explanation. Nothing that could clarify that act, assuming such a gesture can ever truly be explained. Tomasz was a respected music journalist, well known for the radio programs he hosted. If rock music managed to spread in communist Poland, much of the credit was due to his tireless efforts.

After this latest blow, Beksiński could no longer find reasons to leave his house. His natural reserve soon turned into depression. Paradoxically, this hermetic withdrawal from the world, and from everything happening outside the walls of his home, coincided with the peak of his international success. He became a globally recognized artist, with substantial sales and a market increasingly interested in his work.

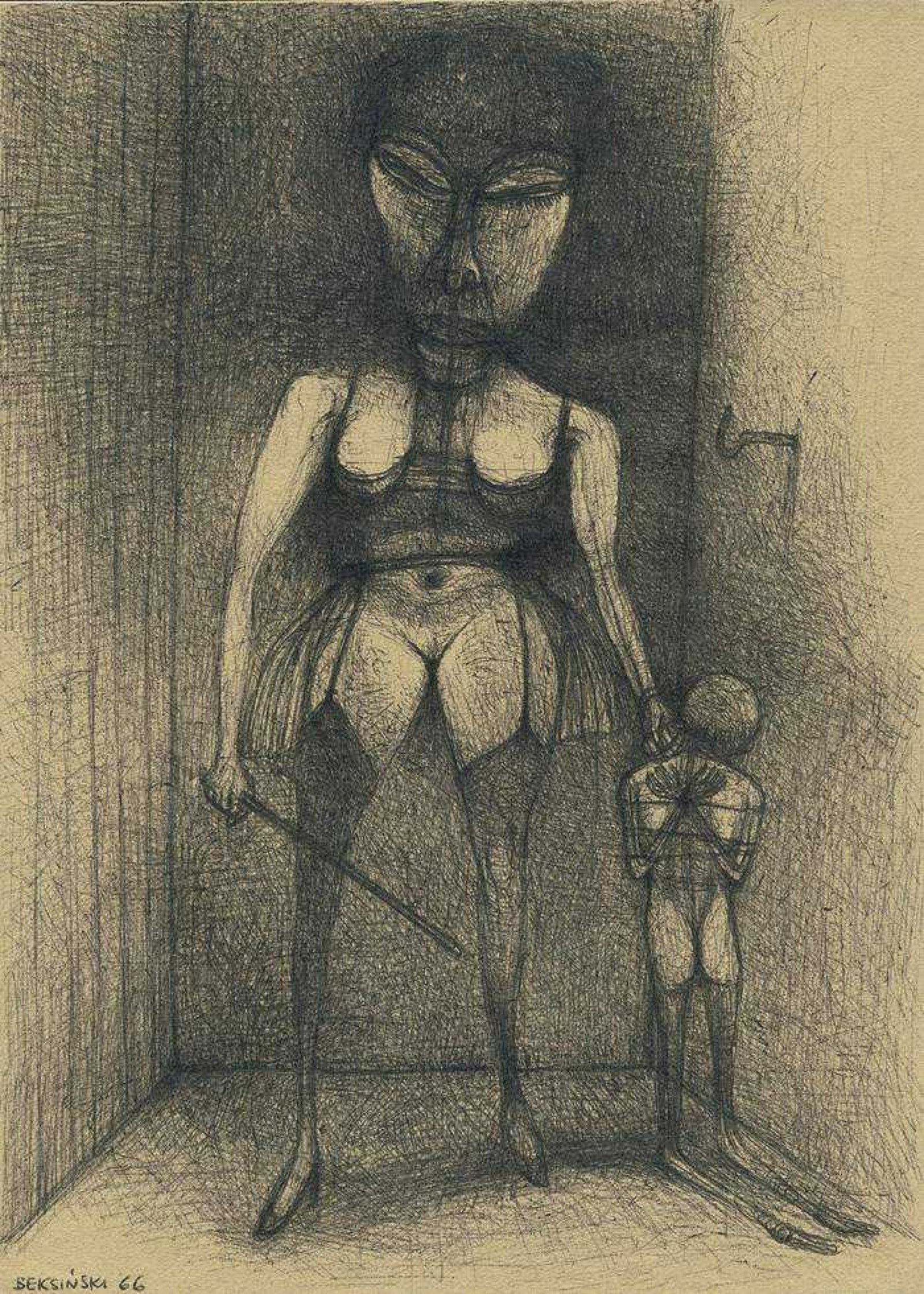

Zdzisław Beksiński, Untitled, 1966

Zdzisław Beksiński, Untitled, 1966

However, Beksiński’s descent into hell finds its tragic conclusion on the afternoon of February 21, 2005. Just when he believes he has already endured all the imaginable cruelties life could inflict, fate strikes him once again.

Beksiński spends that day like many others: hours painting in his studio, surrounded by classical music, pacing the hallways, drinking coffee, reading the newspapers. An aseptic, self-imposed monotony, in which he had willingly imprisoned himself after his son’s suicide.

That day, his butler, Mr. Kupiec, is not on duty. Kupiec has worked for him for a long time: they do not speak much, but for Beksiński, his presence is a silent support, almost a form of companionship. Kupiec has a son, Robert, barely an adult, but with severe drug addiction problems. The young man accumulates debts he can never repay and is constantly seeking money to buy his next dose. Almost inseparable from him is his cousin Łukasz, younger but bound to Robert like a brother.

The two decide to knock on Beksiński’s door to ask for a loan, appealing to his generosity: after all, they reason, the artist is alone, has no more children, and could decide to help them. Beksiński, however, knows very well what the money would be used for—about a hundred dollars, a negligible amount compared to his wealth. Determined not to feed their self-destructive spiral, he refuses their request.

The situation escalates. Robert and Łukasz threaten him, but he manages to drive them out of the house. Later, he decides to tell Mr. Kupiec everything, but the warning proves useless.

On the morning of February 22, 2005, the two young men return. They manage to break into the artist’s home again, this time with knives in their pockets. The threats turn into blind rage.

That cold February morning, Beksiński’s life is violently ended by their murderous fury. He is found brutally slain inside his house, struck seventeen times in the chest and head. A bestial violence, an inferno of demons unleashed upon his now-aged body.

Robert, after confessing, is sentenced on November 9, 2006, to twenty-five years in prison. A lighter sentence is given to his cousin Łukasz, as there was no concrete evidence of his direct participation in the murder, but he is still convicted for perjury and withholding evidence.

Thus concludes Beksiński’s life, one of the most tragic descents into hell. He, who after his accident had tried to keep that inferno at bay, ends up being drawn into it instead, increasingly trapped in his endless web.

There is no explanation for what struck Beksiński and his family. Looking back at his paintings today, it is impossible not to see them as a tragic premonition of what would happen: a life populated by demons, infernal monsters, and desolate landscapes.

Those scenes, which on one hand revealed the deepest fears of his inner world, were also his fortune. A dire premonition, yes, but one that today represents his greatest legacy.

Cover Image: Zdzisław Beksiński, AA78, 1978.

Alessio Vigni, born in 1994. He designs, edits, writes and deals with contemporary art and culture.

He collaborates with important museums, art fairs and artistic organisations. As an independent curator, he works mainly with emerging artists. He recently curated “Warm waters” (Rome, 2025), “SNITCH Vol.2” (Verona, 2024) and the exhibition “Empathic Dialogues” (Milan, 2024). His curatorial practice explores the relationship between the human body and the social relationships of contemporary man.

He writes for several specialised magazines and is author of art catalogues and podcasts. For Psicografici Editore he is co-author of SNITCH. Dentro la trappola (Rome, 2023). Since 2024 he has been a member of the Advisory Board of (un)fair.